World Food Safety Day is celebrated annually on June 7. Established in 2018 through a U.N. General Assembly resolution, the day seeks to bring awareness to foodborne risks and “to celebrate the myriad benefits of safe food,” according to the U.N.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that there are 48 million cases of foodborne illness annually in the U.S. That means that roughly 1 in 6 Americans will contract a foodborne illness this year, and these illnesses are spread through common foods such as produce, meat, fish, dairy and poultry.

Globally, the impact is more significant, with children under the age of 5 and people living in low-income countries hit hardest. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 600 million people contract foodborne illnesses annually, and of those, 420,000 will die. Yet the organization fears that the actual numbers are much higher, as there are places in the world where surveillance data for foodborne illnesses are not available.

The CDC says that most of these illnesses are caused by viruses, bacteria and parasites that are transmitted to humans through the food they consume. This is why food safety is a vital component of the entire agricultural production system and is critical to ensuring food security.

When it comes to researching ways to reduce the impact of harmful microorganisms in the food supply, the University of Georgia has an internationally recognized reputation in food safety research, with microbiologists throughout the university examining ways to improve food safety both within the U.S. and globally.

Leading university research

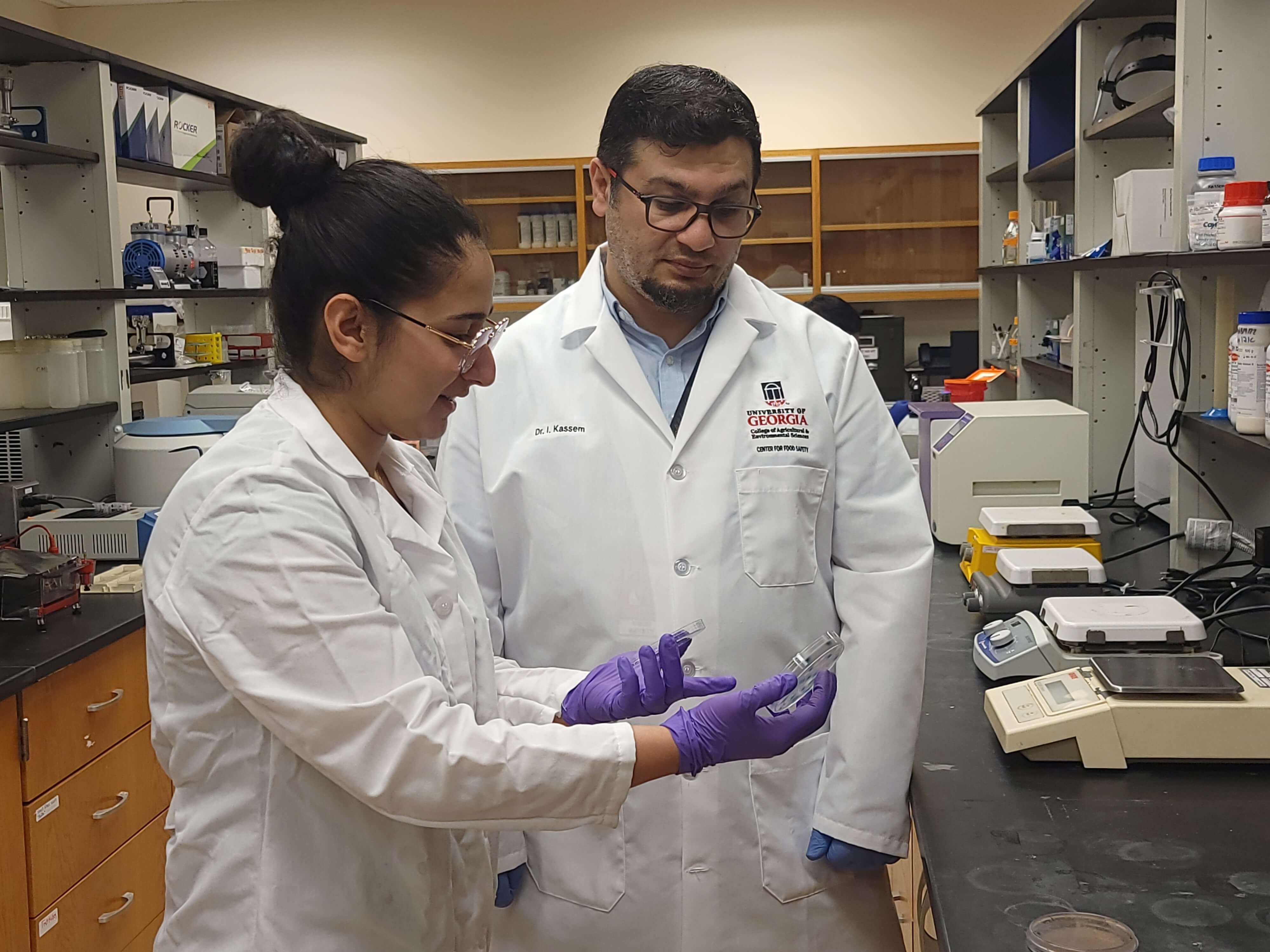

UGA’s food-safety research is led by its Center for Food Safety (CFS), where faculty develop ways to detect, control and eliminate harmful microorganisms and their toxins from the food supply.

CFS often works collaboratively with members of the food industry to help them discover innovative ways to keep food safe. Through its annual meeting and other such collaborations, CFS facilitates the exchange of information to promote the production of safe foods from farm to plate.

CFS researchers focus on four main areas of food safety, starting with preharvest, when researchers study foodborne pathogens before crops are harvested or livestock is slaughtered. Bioinformatics applied to food safety uses whole-genome sequencing, machine learning and data analytics to solve foodborne pathogen contamination issues. CFS scientists develop technologies and ingredients to eliminate or lessen the microbes found in food and the environment and, finally, they study the ecology of food microbes to learn how they survive in food and food-processing environments.

Francisco Diez-Gonzalez, CFS director, said that the declaration of June 7 as World Food Safety Day sends a strong message that keeping food safe is an international responsibility that must be upheld by everyone involved in the food-supply chain.

“I am proud that the CFS mission aligns with the spirit of this day by advancing the understanding of foodborne pathogens and finding solutions to reduce illnesses,” Diez said.

Overlapping initiatives

UGA’s efforts to improve food safety are not limited to the research done at CFS — the work of UGA researchers in other fields often intersect. Professor Catherine Logue’s research in the university’s College of Veterinary Medicine is one example.

Logue specializes in the detection of foodborne pathogens from food animal sources such as poultry. Keeping chickens healthy improves the animals’ well-being, helps farmers retain more birds and affects the quality of the meat. She explained that poultry health is important because the healthier a bird is, the higher quality its meat will be.

“We want the best, healthiest birds out there,” she said.

To that end, she studies how pathogens such as E. coli can be kept in check. Some of her current work looks into strains of E. coli that have become drug resistant. She is also researching ways emerging serotypes of E. coli can be identified early so farmers can be alerted to potential problems. She’s also collaborating with other UGA researchers to help create a single vaccine for chickens that may one day address many forms of E. coli.

Consumer and producer education

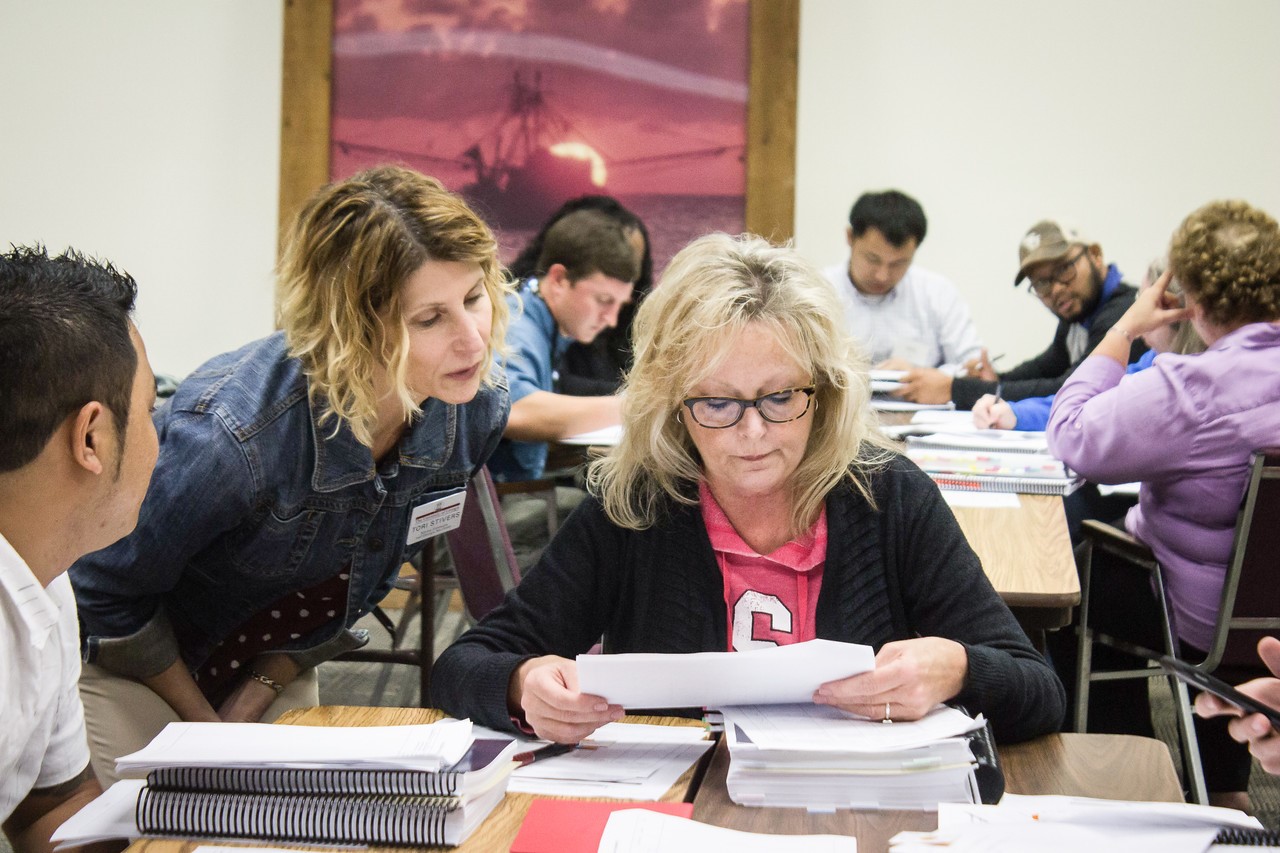

Tori Stivers works at the other end of the food production chain. A public service associate in seafood safety with UGA’s Marine Extension and Georgia Sea Grant, Stivers helps educate wholesalers and consumers about seafood safety.

Stivers teaches wholesalers a Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) seafood safety course — a food safety system that was mandated for the seafood industry by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1997. All seafood wholesalers must have at least one employee certified in the course or hire a certified consultant in order to operate.

The training helps wholesalers analyze their operations to determine where potential hazards may occur and whether they could harm consumers if they aren’t controlled. The FDA-produced manual for the HACCP course is nearly 500 pages, and Stivers teaches class participants how to use it to “determine for themselves what potential hazards are associated with their product and their processing of it, and then determine if they need to control those hazards.”

The HACCP training system requires that wholesalers have a process to control significant hazards within their operations and that they monitor those hazards. Data from the monitoring must be used to keep records documenting operations, and those records must be made available to inspectors when they visit the facilities. Prior to HACCP, inspectors only saw what took place when they were present.

“(The documents) give the inspector a much broader indication of how the facility is managing food safety,” Stivers said.

Stivers also helps to educate consumers, the seafood industry and health care providers about Vibrio vulnificus, bacteria that occur naturally in marine waters and can infect humans through the consumption of raw or undercooked oysters or through open wounds when swimming in waters where it is present.

The bacteria can be fatal, especially to those with compromised immune systems. SafeOysters.org, a website Stivers created and maintains, reports that diagnosis can be difficult because symptoms are vague and, because it is uncommon, medical professionals might not know to look for it.

Industry recognition

There is perhaps no better measure of the caliber and impact of the work of UGA researchers in food safety than through its numerous grants and partnerships.

The Center for Produce Safety (CPS), a nonprofit organization dedicated to increasing the safety of fruits and vegetables, funds research projects worldwide as part its mission to enhance produce safety.

In 2020, they awarded 15 grants to research projects. Of those, one-third were awarded to projects principally led by UGA researchers, and a sixth grant involved UGA researchers. The six grants totaled nearly $1.2 million in research funding for UGA researchers to study produce safety.

UGA researchers frequently partner with such leading institutions as the CDC, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Russell Research Center, the FDA, the Georgia Department of Agriculture, the Georgia Department of Public Health, the Florida Department of Health and many more.

Through its continued research and collaborations, UGA seeks to continue to enhance both the immediate and long-term benefits of a safe food-supply chain throughout the world.

To learn more about the mission, academics and research at the Center for Food Safety, visit cfs.caes.uga.edu.