Halfway through 2022, Earth is on course for another top-10 finish in global temperature. After six months, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported that the period from January through June 2022 was the planet’s sixth warmest on record, with observations that go back to 1880. July has also been warmer than normal in most regions, so that top-10 status is not likely to change.

Getting warmer

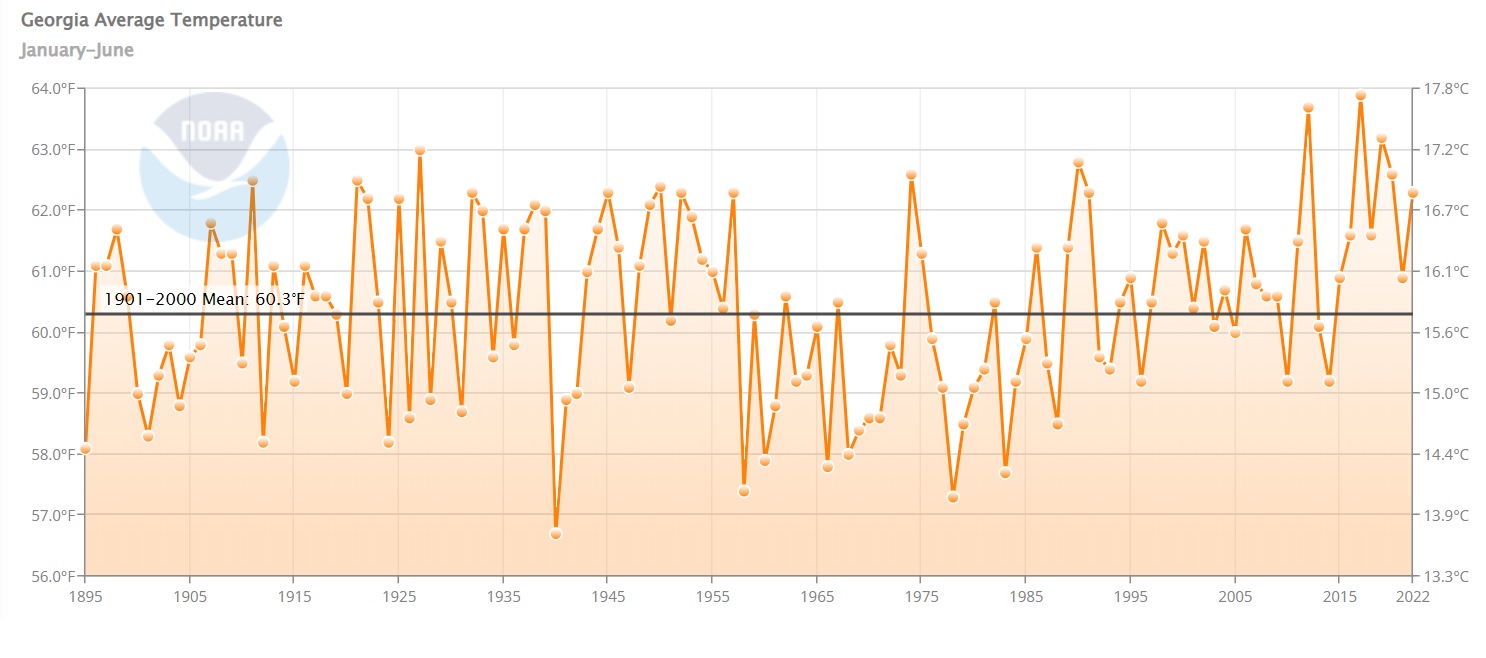

By comparison, Georgia was in a cooler spot on the globe this year. January through June totals were only the 16th warmest for records that go back to 1895, with an average temperature of 62.2 degrees Fahrenheit.

The warmest January through June half-year was in 2017, and the three warmest years were all in the last decade — 2017, 2012 and 2019. Other recent warm January through June periods were 1927 (during an exceptional drought) and 1974, during a strong El Niño.

While there is a lot of year-to-year variability in temperature, Georgia is getting warmer along with the rest of the globe. The major cause of this increase is the addition of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Those gases trap heat near the surface of the earth, where we live.

Other smaller contributions to the warming trend include the expansion of urban areas and the increase in humidity due to warmer ocean temperatures. Higher humidity leads to warmer nights since water vapor also traps heat near Earth’s surface. This is bad for humans as well as livestock since both need cooler nights to recover from the daytime heat.

More urban areas mean more pavement, which heats up during the day and releases the heat at night. There are also fewer trees to produce shade. The increase in humidity is due mainly to the rise in sea-surface temperatures around the globe and the consequent evaporation of water from the oceans.

Outcomes for Georgians

In Georgia, warmer temperatures in winter can cause problems for peach and blueberry farmers, since those crops need plenty of cold weather to produce a large yield in the next growing season. They can also cause problems for commodity crops like corn and cotton, since warmer winters allow insect pests and diseases to overwinter, making them more likely to occur during the next growing season. In the winter of 2021-22, some areas of southwest Georgia did not see their first frost mid-January, which caused problems for farmers as their crops developed over the summer.

Warmer temperatures in winter can lead to lower power bills, as heating may be needed for fewer hours. But in summer, air conditioning costs are expected to increase significantly since hotter summers require more cooling. This is especially serious for people who live in cities, where the heat is often 10 degrees or more higher than rural areas outside the populated areas. If residents in those areas do not have access to good air conditioning, they are in danger of dying from heat-related illnesses.

Warmer temperatures also have other effects. The growing season is starting to occur earlier than it has in the past. This may be good for farmers who are eager to start a crop, but it means that pollen also starts earlier and the pollen season lasts longer than it did years ago. It also means that flowering trees and plants that provide food to birds and pollinators may start to bloom so early that the animals that depend on those plants have not migrated north into our area. This means they are likely to starve due to lack of suitable food sources.

That said, warmer conditions do have some positive effects. Warmer conditions allow farmers to grow new crops like satsuma citrus, olives and pomegranates, which need warm conditions to thrive. A longer growing season could give farmers more chance of growing two crops in one year, a method known as “double-cropping.”

While temperatures are getting warmer, precipitation is also changing. Higher temperatures lead to more evaporation and an amplified water cycle. That means more floods and droughts may occur because rain will come down in heavier bursts, with longer dry spells in between. This will cause problems for agriculture, transportation and other infrastructure, and human health.

Melting sea ice

The NOAA report also stated that sea ice is decreasing in both the Arctic and Antarctica as a consequence of warming global temperatures. According to NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information, Antarctica saw its lowest June ice coverage on record.

As the sea ice melts, the poles get even warmer than the mid-latitudes because of the decrease in reflective snow and ice. This can have consequences for Georgia by changing the large-scale weather pattern across the Northern Hemisphere, which is driven by temperature differences between the Equator and the North Pole. If that temperature difference changes, the pattern of atmospheric flow may also shift, bringing unexpected weather to our state.

By reducing the emission of greenhouse gases, we may be able to reduce the amount of warming in the future. You can help by reducing your use of power and fossil fuels and cutting food waste, which releases methane, another powerful greenhouse gas, when the unused food decays.