How did your garden grow in 2024 — was it a lush playground full of beautiful flowers and plentiful produce? Or was it a sere landscape of brown, wilted foliage? How your own garden fared in 2024 was certainly dependent on where you live, what you planted and how you took care of it, but it was also subject to the variations in weather and climate in your area.

As the new year gets underway, let’s look back at the climate conditions of 2024 and look forward to what last year's trends may indicate for 2025.

What controlled the climate around the world in 2024?

Data shows that 2024 was the warmest year on record since official global tracking began in 1880. Three main factors controlled the climate in 2024, although there are also local variations due to smaller-scale weather events. Contributing factors include the warming trend across the world caused by greenhouse warming of the planet, the El Niño that dominated the eastern Pacific Ocean in the first half of the year, and the unusual warming of the Atlantic Ocean, which fueled the growth of Atlantic tropical cyclones and raised global temperatures.

Impacts of the rising temperature trend

Rising world temperatures are well-documented by scientists around the globe. They are generally linked to increases in the amount of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane from sources like the burning of fossil fuel. This is not a new concept and can be found in scientific literature dating back to at least 1856, when Eunice Foote discovered that carbon dioxide trapped heat in her home laboratory. Many scientists have since corroborated that effect, and others have shown that the primary source of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide is the burning of fossil fuels, although there are additional sources.

A timeline of global temperatures for January through December shows that 2024 was the warmest year on record so far, beating the next warmest year, 2023, by 0.18 degrees Fahrenheit. However, since temperatures are still rising, we can expect to see more record-setting warm years in the future. The rise in global and regional temperature occurring now may not be apparent on a day-to-day basis due to short-term variations caused by passing weather systems.

Still, the changes are reflected in increases in normal temperatures when they are updated every 10 years. Longer-term changes like the drift in Plant Hardiness Zones also reflect this upward trend. Heat waves across Northern Europe and South America in 2024 have been attributed in part to the warming trend. Of course, winter will still occur, and we will continue to have cold periods, just fewer than in the past.

El Niño to neutral conditions

The second major impact on the climate in 2024 was the lingering El Niño that occurred as 2024 began and lasted until early June. The warm water in the eastern Pacific Ocean associated with El Niño helped raise the global temperature during the first half of the year and affected the climate worldwide.

In North America, an El Niño is associated with warm, dry conditions at high latitudes and wet, cool conditions in southern latitudes as the jet stream is shifted to the south, bringing storms, clouds and rain along with it. Once the El Niño ended in June, neutral conditions prevailed until late in 2024.

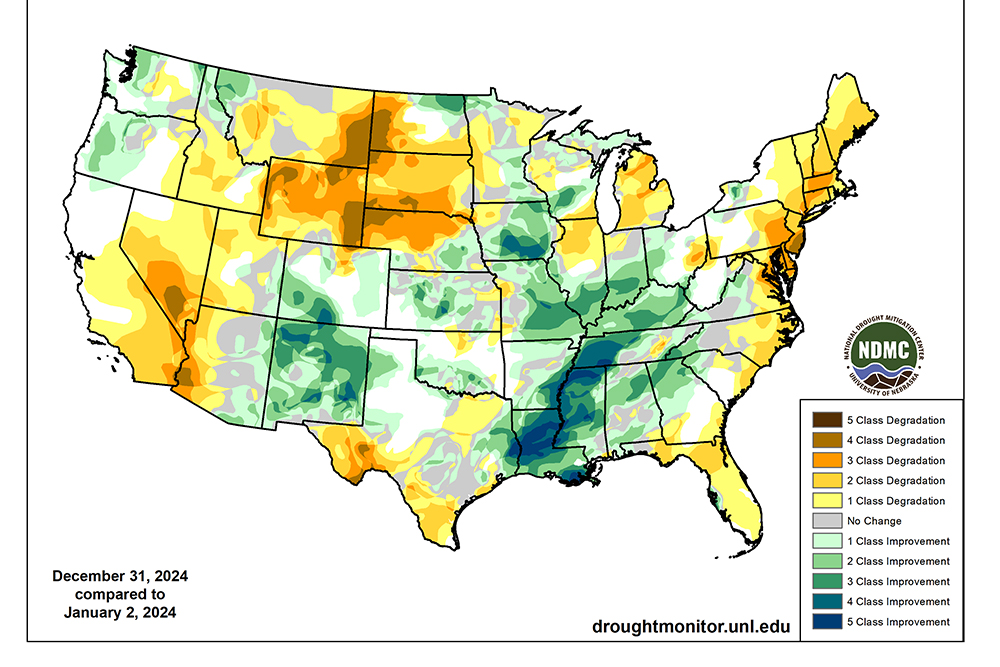

In the last month, conditions finally reached the threshold for the opposite phase, La Niña. Climate patterns associated with La Niña started appearing late in 2024, leading to dry conditions across southern parts of the U.S. and wet conditions farther to the north. In fact, in the Southeastern U.S., most areas were in drought for a good part of the summer except areas that were hit by tropical cyclones like Beryl, Debby, Francine, Helene and the remains of Rafael. By the end of 2024, more than 87% of the lower 48 states were covered by drought or abnormally dry conditions, a big change from early in the year.

Notable droughts also occurred in Brazil, other parts of South America and Northern Europe. These droughts were also associated with record-setting warm temperatures as high pressure over those areas tamped down any development of rainstorms and caused clear skies, which increased temperatures.

Record-setting highs in the Atlantic

The third impact on this year’s climate was the abnormally warm temperatures in the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. These record-setting temperatures have been linked to decreases in aerosols from the burning of fossil fuels by ships crossing the ocean and, in more recent literature, to decreases in low clouds over the ocean. Both can lead to more sunlight reaching the surface of the ocean and increasing its temperature.

Warm sea surface temperatures led to a larger number of tropical systems than usual in the Atlantic Ocean by providing a source of fuel that helped them develop into full-fledged tropical storms and hurricanes. There were 11 hurricanes and 18 named storms in the Atlantic Basin in 2024, the fifth-largest number in the satellite era. The number and intensity of tropical cyclones in other parts of the world, including the western Pacific, are also attributed in part to warmer ocean water. The Philippines experienced five typhoons in just a few weeks, causing tremendous damage there, and other areas of Southeast Asia also felt the impacts of tropical systems.

What should the U.S. expect from the weather in 2025?

La Niña was declared in early January as temperatures in the eastern Pacific Ocean finally dropped below official thresholds. Still, we can predict that the early part of the year will show the characteristic pattern of a weak La Niña, including a shift to the north for the jet stream over the U.S. That will bring cloudy and colder weather to the North and warmer and drier conditions to the South as the jet stream pushes precipitation-producing systems around. These conditions will likely be reflected in the soil moisture present during the spring planting season, so I expect dry conditions in the Southeast that could affect the germination of seeds.

Wetter conditions in the North should prevent this problem, but farmers could have trouble getting into the fields to plant if it is wet and cool, leading to delays in establishing crops. This La Niña is likely to be fairly weak, so it may only last for a before we return to neutral conditions. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts that the neutral conditions will likely last for most of the summer, meaning we are likely to get another active Atlantic tropical season. The South could be fairly dry except for where the tropics bring storms to the area again in 2025.

Subscribe to regular climate and agriculture updates from University of Georgia Cooperative Extension at site.extension.uga.edu/climate.