From the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, experts and health officials have witnessed a wide variety of symptoms — one patient may have a severe cough, while another may have no symptoms at all.

While reported symptoms were predominately respiratory, a percentage of patients also reported digestive issues such as upset stomach and diarrhea. A new study by University of Georgia virologist Malak Esseili points to the reasons that some patients have gastrointestinal issues with COVID-19 and others do not.

“We know that the virus is respiratory, but we didn’t know whether there were other routes of transmission,” said Esseili, who wanted to examine if food is a transmission route for the virus. “We know other viruses do it. Animal coronaviruses do it, so why not SARS-CoV-2?”

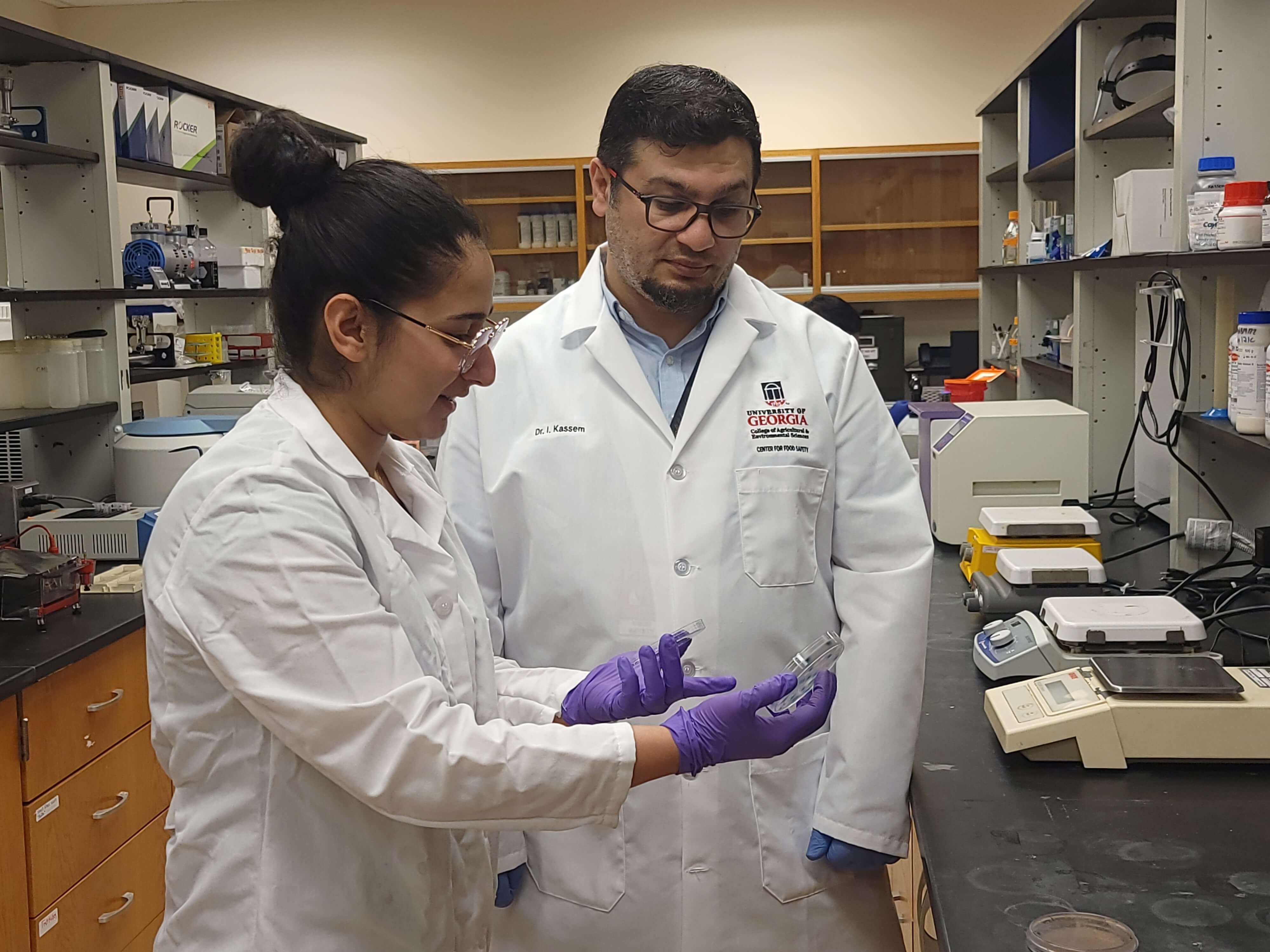

A virologist at UGA’s Center for Food Safety in the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, Esseili has often worked with norovirus, which causes nausea, vomiting and diarrhea and is easily transmitted by infected people and through food and water.

Scientists classify viruses by the bodily systems they infect. Viruses that infect the nose and lungs are called respiratory and those that infect the digestive system are classified as enteric. From the onset, experts knew that COVID-19 was respiratory, as it predominantly infects the lungs, but Esseili said there was plenty of evidence that the virus has enteric properties.

Esseili built on an earlier study that examined the use of proton pump inhibitors while infected with SARS-CoV-2. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are common medications often sold over-the-counter to help reduce ailments such as heartburn or acid reflux. The research found that when PPIs were used in conjunction with COVID-19, it resulted in more severe cases for some patients. Esseili wanted to know how.

When she began her research, it was generally believed that the digestive system could stop, or inactivate, the virus due to the high acidity of the stomach. Esseili explained that levels of stomach acidity can fluctuate widely and are influenced by various conditions. For example, when the stomach is empty, such as when a person first wakes up in the morning, the level of acidity is high. When a person eats a large meal or takes certain medications such as PPIs, the acidity is low.

When the acidity is low, Esseili found that SARS-CoV-2 can easily survive in the digestive system, even though it is an enveloped virus. An enveloped virus has a lipid, or fat, layer around it that is traditionally thought of as being easy to degrade. Things such as detergents are one way of degrading this fat layer. Researchers assumed this easily degraded envelope was another reason that SARS-CoV-2 would break down in the digestive system.

More surprising was the finding that bile, which is a component of the digestive juice needed to help absorb fats in the intestine, has less of an effect on SARS-CoV-2 than expected. The amount of bile produced is affected by how much a person eats. When a person eats a large meal, they produce large quantities of bile to aid in digestion. Yet the study found that these high levels of bile did not inactivate the virus to the degree that the researchers expected.

“When a person first wakes up in the morning and drinks a glass of water, the stomach acidity is high and the intestinal bile is low. There we see the highest level of virus inactivation both by the stomach and the intestine. This is opposite to what we see during feeding when stomach acidity is lower and bile is high. This was a surprise to us,” Esseili said.

“We used to think the acidity of the stomach was going to inactivate the virus so it cannot pass that harsh route, but our data show that the virus can escape stomach acidity and bile under certain conditions and go to the intestines and replicate. It proves that SARS-CoV-2 also behaves as an enteric virus,” she said. “This is a major shift in how we think about the virus, and whether oral ingestion of the virus on food, for example, is a route of transmission.”

Esseili says further research is needed to understand the full implications, but that this finding helps lay to rest one mystery of the pandemic: why some people with COVID have digestive symptoms and others do not.