.jpg)

Often referred to as leafy greens, lettuce and other similar vegetables are a common source of foodborne illnesses.

The contamination of lettuce with Escherichia coli O157:H7, also known as EcO157, has been a grave concern for decades. Causing numerous cases of illness and death, this strain of E. coli threatens both public health and a U.S. industry valued at more than $2 billion annually.

To address this threat, researchers at the University of Georgia Center for Food Safety are preparing to launch a study on E. coli colonization from a new angle: the microbiome of lettuce.

By studying the interactions between EcO157 and the lettuce microbiome — the entire community of microorganisms like bacteria that live on the surface of lettuce — researchers hope to better understand how the microbiome may affect the pathogen’s fate during produce processing.

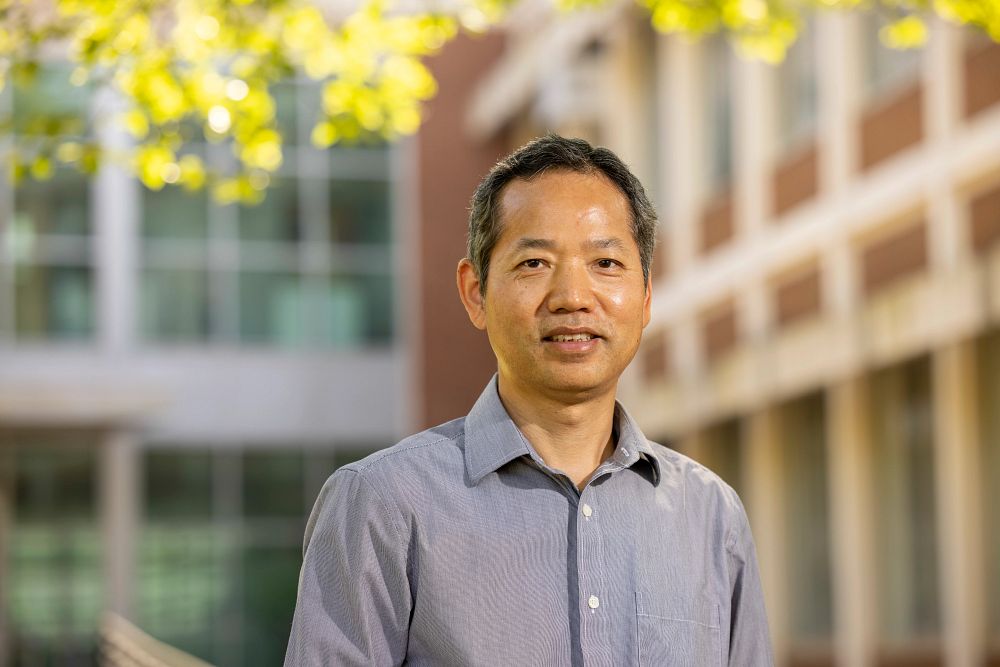

Center for Food Safety Professor Xiangyu Deng, lead researcher on the project, said, “We want to really figure out the interactions between the pathogen and potential biocontrol organisms indigenous to lettuce.”

In other words, how does E. coli interact with other microorganisms on lettuce, and how can we use those interactions to control foodborne outbreaks? EcO157 is one of the most commonly identified types of Shiga-toxin producing E. coli, a common cause of foodborne disease.

The focus of the research, to start this year, will be how the microbiome interacts with EcO157.

“Clearly the microbiome interacts with EcO157, and that interaction has an implication for food safety. We want to understand the mechanism behind this interaction,” Deng said.

The team will use a new microscopic approach to create a biogeographic map of the microbiome.

.jpg)

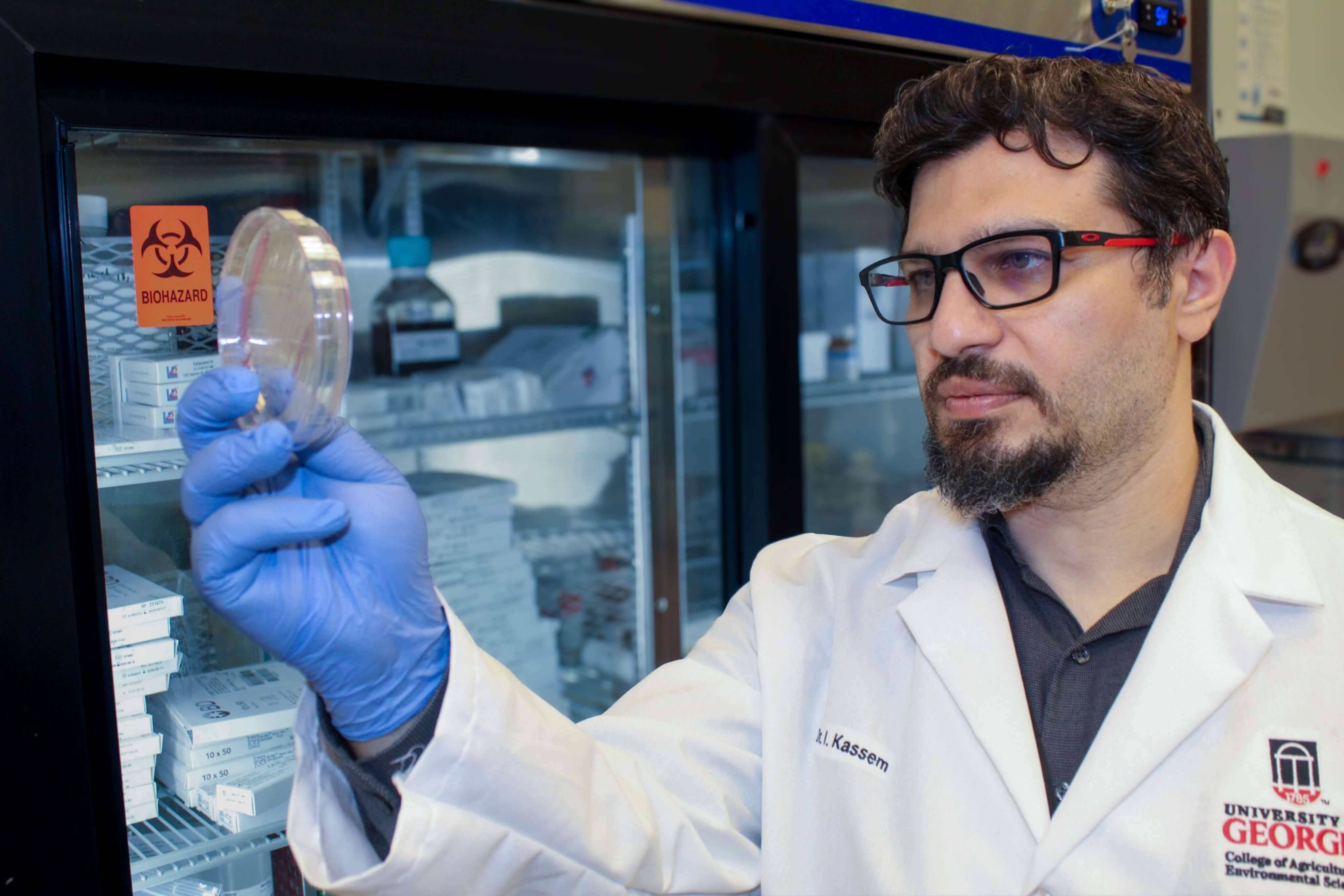

This breakthrough technology, called high-phylogenetic-resolution microbiome mapping by fluorescence in situ hybridization — or its more pronounceable acronym, HiPR-FISH — allows researchers to locate and identify hundreds of microbial species in the microbiome at a single-cell resolution.

Hao Shi of Kanvas Biosciences, who was involved with the development of HiPR-FISH, will assist in the research, joined by Maria Brandl of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Edward Dudley of Pennsylvania State University.

Researchers hope to use the study results to explore ways to control E. coli O157:H7 in lettuce — either by altering the microbiome itself or by making changes to how the lettuce is processed for sale. Or both.

Some bacteria that exist on the lettuce leaf may help stop or reduce the spread of EcO157 using a method called biological control, or biocontrol for short. If so, the results of the study may help researchers understand which bacteria already do this and how to maximize their effectiveness.

The team will also evaluate the potential of possible biocontrol bacteria as a hurdle to EcO157 colonization in bagged lettuce, determining the effectiveness of these beneficial bacteria by applying them to lettuce inside sealed packaging.

The grant of nearly $850,000 was awarded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture as part of its Agriculture and Food Research Initiative (AFRI) competitive grants program. The study is expected to conclude in May 2026.