Consumers have long been warned against the hazards of eating raw cookie dough. As more cases of foodborne illness are linked to contaminated wheat flour, University of Georgia food safety experts are touting the risk in a louder, more forceful voice, while searching for ways to eliminate foodborne pathogens on wheat products.

In wheat-related cases, the common carriers of the pathogens are cookie dough, cake batter and raw wheat flour. The most recent outbreak started in May and was linked to wheat flour contaminated with E. coli 026 bacteria. Three brands of contaminated all-purpose flour were found at grocery stores in eight states, to date. So far, 21 cases of E. coli 026 infections have been reported.

In 2005, 26 cases in the U.S. were linked to cake-batter ice cream and in 2008 a cluster of cases in New Zealand were connected to an uncooked baking mixture. In all of these cases, the pathogen was Salmonella. In 2009, an E. coli O157:H7 outbreak resulted from consumption of raw cookie dough.

“In the past, the reason we warned people not to eat cookie dough was not because of the flour, but because of the raw eggs,” said Francisco Diez, director of the UGA Center for Food Safety located on the university’s campus in Griffin, Georgia. “The two main pathogens linked to wheat products are Salmonella and E. coli.”

Diez says these cases could have been prevented if the flour had not been consumed raw.

“Flour is not meant to be consumed raw and cookie dough is still raw flour. You have to avoid consumption of foods that contain wheat flour unless they are baked, fried or cooked otherwise,” he said. “For the most part, as long as you bake what you make with the flour, you should be okay.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), it can take two to eight days for the body to present symptoms after ingesting the bacteria. For some people, like children and those who are immunocompromised, the illness can lead to serious symptom and even kidney failure.

UGA Cooperative Extension Food Safety Specialist Elizabeth Andress advises consumers who have flour from the recent recall not to use it and to discard it. If the flour was stored outside its original bag, she says to thoroughly wash and dry the flour container before using it again.

“Eating raw doughs, batters or any recipe that contains raw flour can make someone sick,” she said. “Children and others should not be allowed to play with raw dough made from any flour.”

Diez, who has researched ways to keep America’s food products’ safe for the past 20 years, says that the best of line of protection when handling raw flour is to always cook the food, unlike fresh spinach and lettuce where there is little consumers can do to further protect themselves.

“One outbreak came from restaurants giving kids raw dough to play with and those kids got sick,” Diez said. “It involved quite a few children who had all gone to the same restaurant and played with raw dough.”

Most foods that contain wheat flour are baked, cooked or fried. The heat quickly kills the organisms so there’s no reason to be concerned, Diez says. The number of food product recalls linked to wheat has increased, but Diez says that this is in part due to the food industry’s sharper focus on wheat as a possible carrier.

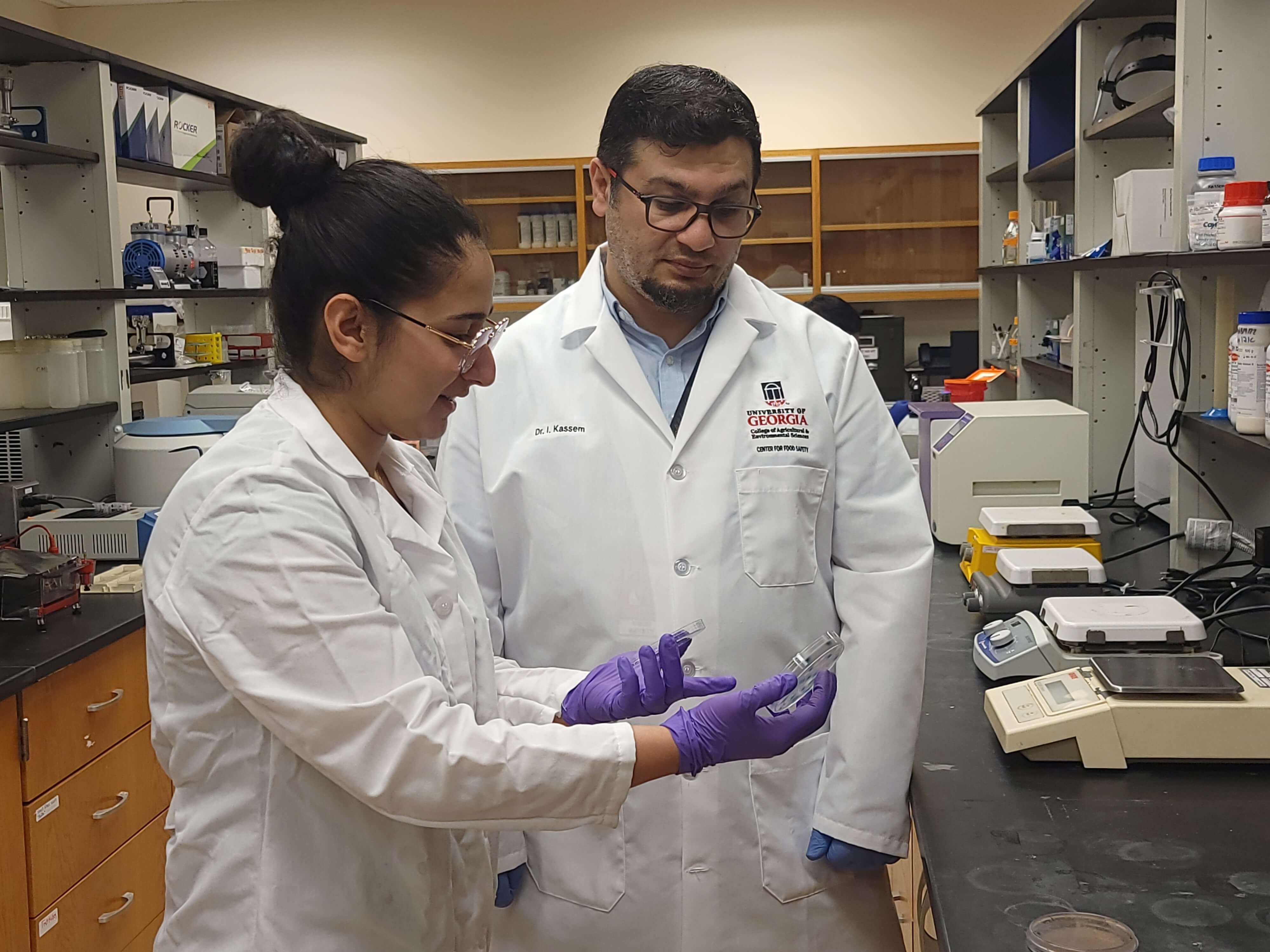

At UGA’s food safety center, Diez and his team are working closely with the food industry and the CDC to identify ways to eliminate foodborne pathogens on wheat.

“We know Salmonella can be found in dry foods and wheat flour, but we don’t know a lot about E. coli in wheat flour,” he said. “We need to know more about microbial pathogens in wheat in order to develop effective methods to prevent foodborne illnesses caused by wheat products.”

From 2012 to 2014, a study examined over 5,000 wheat samples to determine the prevalence and levels of pathogens before the berries are milled into flour, Diez said. Salmonella was detected in 1.23% of the samples, E. coli occurred in 0.44% of the samples, Listeria spp. occurred in 0.08% of samples and L. monocytogenes was not detected.

UGA’s most recent research shows that E. coli can survive in flour stored at room temperature for up to one year and Salmonella can survive under similar conditions for nine months. Heat treatment was found to be an effective method for reducing the risk of E. coli in flour, but was less effective in reducing Salmonella numbers.

UGA research also found that storing flour at slightly higher temperatures (95 degrees Fahrenheit) for a minimum of two months before distribution can be an effective strategy for reducing both E. coli and Salmonella numbers.

Some flour companies have begun to heat-treat or pasteurize their flour to reduce pathogens; unfortunately, this can affect the quality, Diez said.

Pasteurization of flour, however, is not always available or appropriate for flour quality, Diez said, so UGA researchers are investigating the development of novel intervention strategies.