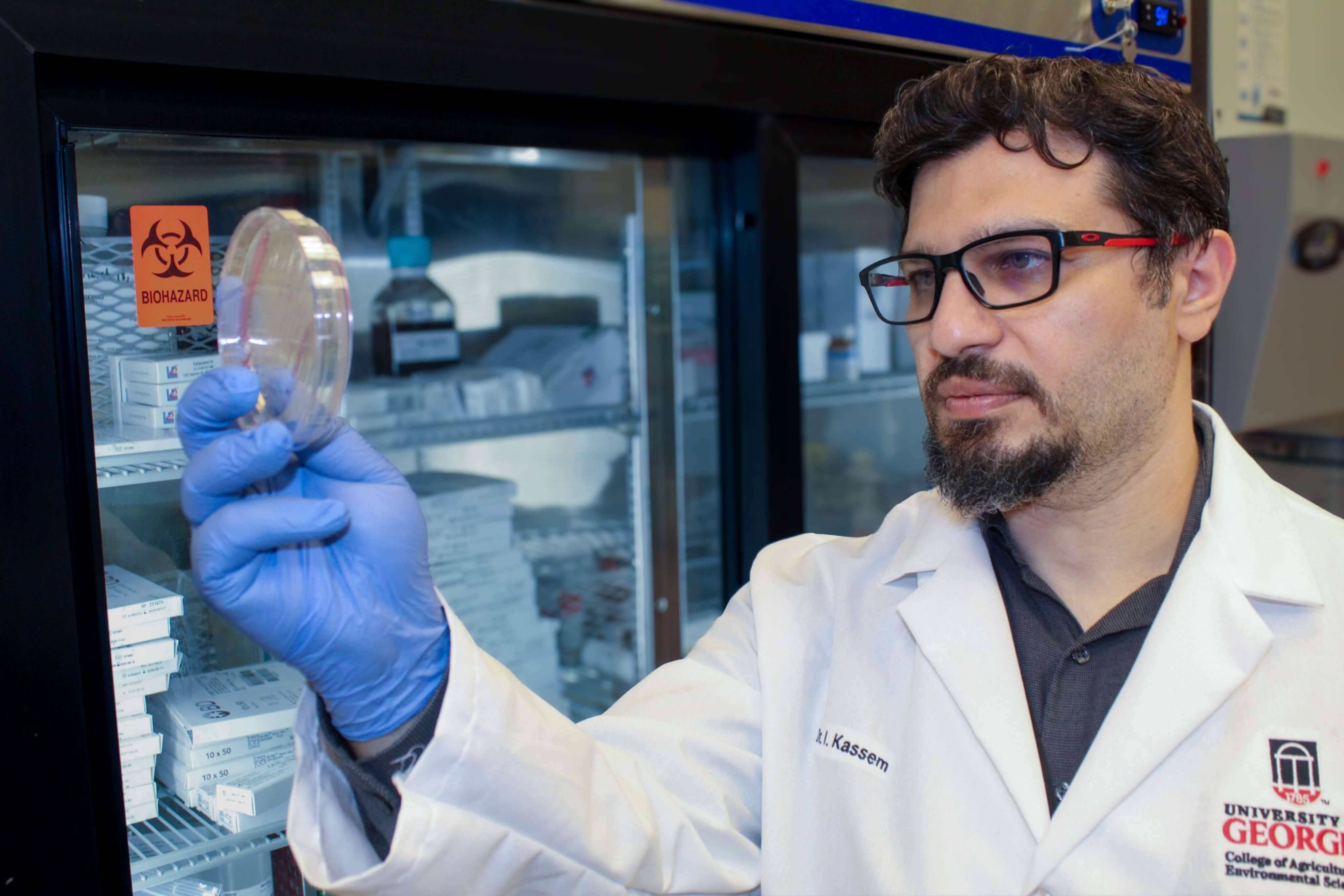

Pecan scab — a fungal disease — reduced Georgia’s projected pecan crop by almost half this year. That’s extra motivation for Patrick Conner, who’s attempting to breed a scab-resistant pecan variety at the University of Georgia Tifton campus.

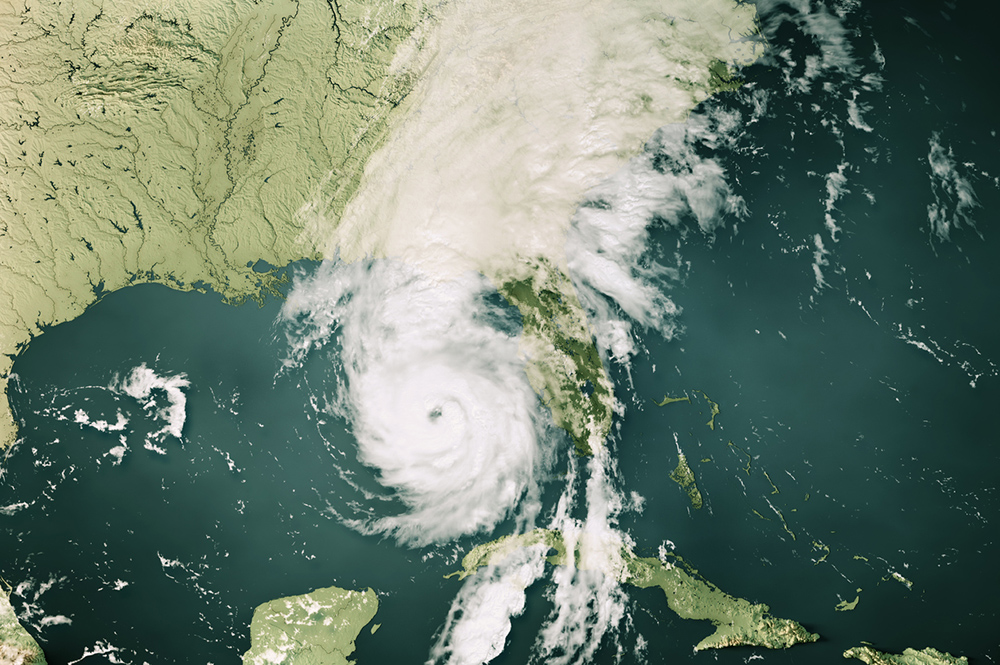

“We had serious losses this year because of all the rain and pecan scab,” Conner said. “We’re trying to combine high scab resistance with large nut size and high quality.”

Developing a new pecan variety that’s resistant to scab, which thrived due to excess rainfall this past summer, has not been an easy task for Conner.

The disease affected two of Georgia’s most common pecan cultivars — Desirable and Stuart trees — but the disease is not uniform across tree varieties.

“It’s extremely difficult because scab is native to this region, and it’s co-evolved with pecans. What we’ve found in doing tests is that there’s not just one kind of scab. There are multiple races of scab, so if you take scab off a Stuart tree and put it on a Desirable tree, the Desirable tree is resistant to that Stuart scab and vice versa,” Conner said. “Just as there are lots and lots of different cultivars of pecans, there are many, many races of scab.”

Scab has long been a problem for pecan farmers throughout the state and is a reason the breeding program started in 1999. For the first six to nine years of the program, Conner crossed different varieties and planted the resulting seeds.

Because it takes several years for the tree to become large enough to start bearing fruit, it’s only been the last five or six years that UGA scientists have been able to rate the breeding program trees for the size and quality of their nuts. Those with the best nut quality and good scab resistance are now being placed into yield trials to determine if they are productive enough to use for commercial pecan production.

Of about 12,000 seedlings planted, Conner has kept 17 selections for yield trials.

“It takes so much time and effort to do yield trials, you really only want to keep ones you think have a chance as being released as a new cultivar,” Conner said.

Conner hopes that he can release one of these scab-resistant cultivars within the next five years.

“I think it’ll be a good seller if it does go out. Different growers have different needs in what they’re looking for in their operation. Middle Georgia, for instance, has much less scab problems than, say the Albany or Valdosta area. For them, maybe something that’s higher quality and higher yielding might be more important than scab resistance,” Conner said.

Along with trying to produce a scab-resistant cultivar, Conner has also worked with producing very early-yielding cultivars, so that Georgia farmers will have pecans ready to harvest in September rather than October. In many years, the earlier the pecans can be collected and sold, the higher the price will be for farmers. Early harvest is one advantage Georgia has over the Western pecan region. The state’s crop already is harvested much earlier, when the demand is higher.

Conner is also looking at establishing a cultivar that’s more regular in bearing its fruit year after year. Pecan trees are notorious for producing a crop that is strong one year and not as strong the next. Conner is crossing cultivars that are more regular in bearing fruit with a goal to find more consistent-bearing varieties.

For more information about UGA’s pecan breeding program on the Tifton campus, see caes.uga.edu/commodities/fruits/pecanbreeding.