When the coronavirus pandemic first began in 2020, there was much that officials did not know about the virus and how to combat it. One area of concern was how to disinfect surfaces that were contaminated with SARS-CoV-2. Institutions such as schools and daycares especially needed to know how to clean high-touch surfaces to reduce the risk of infection.

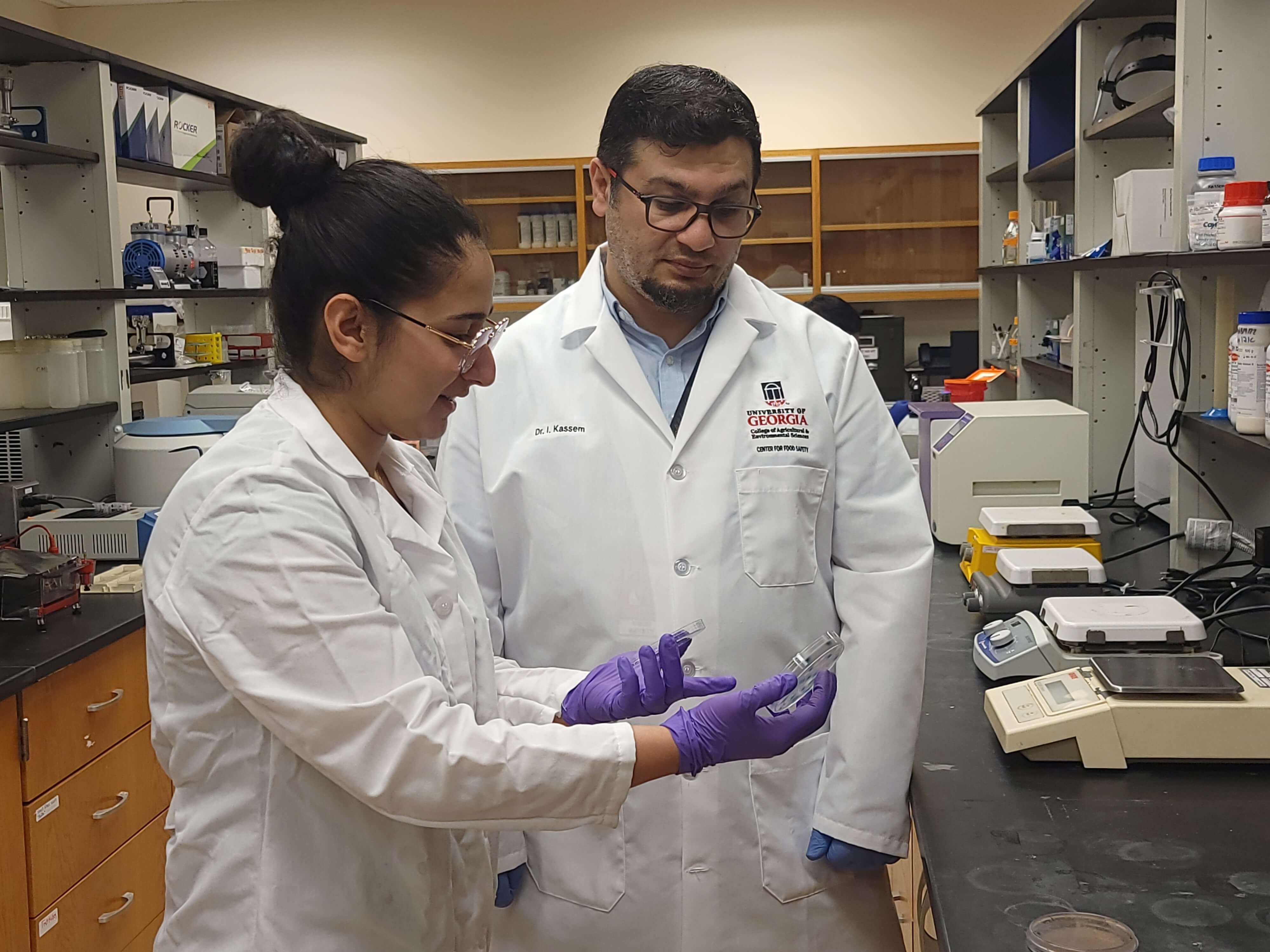

Malak Esseili, a virologist at the University of Georgia Center for Food Safety within the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, began researching methods of inactivating SARS-CoV-2 on surfaces in 2021.

Her team discovered that the recommended guidelines for chlorine in community settings fell short of what is required to successfully treat contaminated surfaces and reduce the spread of coronavirus. This is especially true when these surfaces are not cleaned first. These findings are out now in the journal of Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

“The World Health Organization put out guidelines that recommended using 1,000 parts per million of chlorine for at least one minute on high touch surfaces such as doorknobs, bathroom surfaces, work surfaces,” Esseili said. “We discovered that this was ineffective if a prior cleaning step was not conducted.”

Because of the new and unknown nature of the virus, officials were forced to offer sanitation guidelines that applied to other, harder-to-kill pathogens without testing the recommendations on SARS-CoV-2.

Further testing has shown that chlorine in the suggested concentration must sit for 10 times longer than the recommended guidelines to be effective on uncleaned surfaces. This means that following the suggested guidelines in a home where the virus was present would not remove it from contaminated surfaces if surfaces were treated only with the disinfectant without cleaning the area first.

Because chlorine is corrosive, increasing the concentration of chlorine can be dangerous to inhale in large quantities, presenting a health danger. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cautions that it can cause “changes in breathing rate, coughing and damage to the lungs,” warning that some symptoms can be severe.

Looking for an alternative, Esseili’s team discovered that peracetic acid, a colorless liquid used as a sanitizer in food production, is a viable option. Peracetic acid, which is effective against microorganisms, is often considered to be “greener” than chlorine because it breaks down into components that are less harmful to the environment. However, only two studies have been done to evaluate its effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2, and those studies were not performed on contaminated surfaces.

“At relatively lower concentrations, peracetic acid was effective against SARS-CoV-2 on uncleaned surfaces and can be used as safer and more environmentally friendly alternative to chlorine. Specifically, peracetic acid at 200 parts per million (ppm) for 10 minutes was effective against SARS-CoV-2 on stainless steel and high-density polyethylene surfaces, whereas chlorine required 1,000 ppm (five times the concentration of peracetic acid) for 10 minutes to be effective against SARS-CoV-2 on both surfaces,” Esseili said.

Peracetic acid, as it is currently produced, requires specialized handling in its use disinfecting medical, surgical and dental tools. It is currently not recommended for consumer use. More research is needed to adapt it before it can be safely used in a home or similar setting, Esseili said.

Ongoing research is needed on the development and use of sanitizers and disinfectants against emerging and re-emerging pathogens, but Esseili hopes that the findings will be a model for how to safely and effectively disinfect surfaces contaminated with envelope viruses like coronavirus, especially when there is no time to pre-clean and then disinfect.

Learn more about research at UGA's Center for Food Safety at cfs.caes.uga.edu.