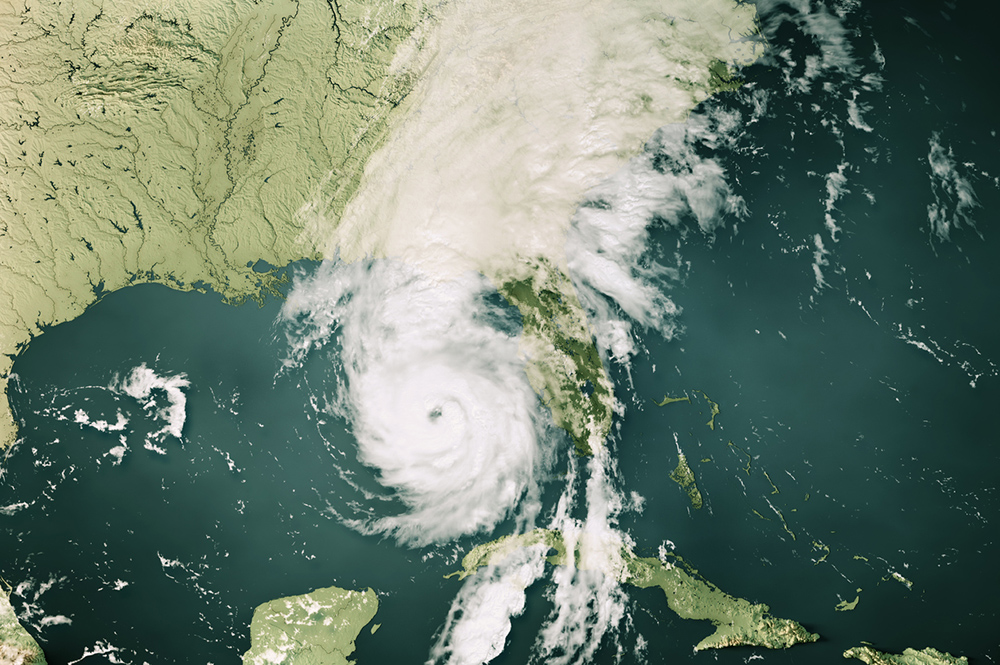

Using fertilizer to increase crop yields in sub-Saharan Africa may seem like a logical choice, but farmers in rain-fed areas must also weigh the potential for low rainfall or excess heat during the growing season.

When the risk of crop failure from climatic conditions, which varies from location to location, is incorporated into farmers’ rate of return calculations, it does not make sense for many smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa to use fertilizer, according to a study led by a University of Georgia researcher that was recently published in the journal Nature Food.

Ellen McCullough, assistant professor in the University of Georgia's Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics at the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, led the analysis of a large agronomic trial dataset covering 13 years and 17 sub-Saharan African countries estimating the maize yield response to using inorganic fertilizer based on soil characteristics and growing season climate.

The study aimed to highlight how uncertain economic returns are for smallholders — who often manage farms under five acres — using fertilizer, given that they must purchase fertilizer at the start of the growing season without knowing whether they will face good or poor growing conditions.

The research team developed a new analytical framework for thinking about this important input decision from the farmer’s perspective.

The researchers used their fertilizer yield response model to predict how risky it was to use fertilizer for a large portion of maize-growing areas in sub-Saharan Africa given each location’s rainfall and temperature possibilities and soil conditions. They found that in about one-fourth of rain-fed maize-growing locations in sub-Saharan Africa, farmers cannot expect to clear a 30% rate of return on fertilizer use at least 70% of the time.

“In our analysis, farmers in many locations could not expect a good rate of return often enough to justify investing in fertilizer. With fertilizer prices almost doubling in 2022, many more smallholder farmers in rain-fed areas are likely wondering whether it makes sense to buy fertilizer,” McCullough said.

Evidence from other parts of world — such as Asia and Latin America — shows that using improved crop varieties combined with inputs like inorganic fertilizer have contributed to major increases in yields and production. The economic environment in sub-Saharan Africa, however, makes use of these inputs more financially risky for farmers who have limited access to financing.

“Farmers in Africa need to pay much higher interest rates to finance fertilizer purchases, so the costs can really be prohibitive,” McCullough said. “Farmers in Africa also face higher transportation costs, which often means they must sell their crops for lower prices. These costs can eat into farmers’ profit margins.”

Eighty percent of farmland in sub-Saharan Africa is cultivated by smallholders, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. And smallholder farmers provide up to 80% of the region's food supply.

The problems and considerations faced by farmers in sub-Saharan Africa are “complex and multifaceted,” McCullough said.

“I think this study really highlights future research directions in trying to understand why farmers might not be adopting an input like inorganic fertilizer, which is often promoted as an obvious blanket solution to low smallholder productivity in sub-Saharan Africa,” she added. “It is time to revisit whether farmers’ reluctance to adopt fertilizer can be explained by the fact that it just does not make sense economically for them to do so. Interventions to improve the financial incentives to use fertilizer, like de-risking the investment with better insurance, improving access to financing or improving output markets, could be more effective than interventions to educate farmers about fertilizer.”

Co-authors of the study include Julianne D. Quinn, an assistant professor of engineering systems and environment with the University of Virginia, and economist Andrew M. Simons with Fordham University.