Over the past few years, “clean eating” has become a popular way to describe a diet of simple foods, and food manufacturers have taken note. Following consumer demand, food companies have simplified their ingredient lists, introduced clean labeling and started to advertise their products as “clean.”

The demand for clean labeling and simple ingredients has pushed companies like Nestle, Papa John’s, Dannon and many others to simplify their food labels to keep up with competition, which isn’t an easy feat.

In 2015, clean-label foods and beverages reached an estimated $165 billion globally, according to Food Business News. That figure is expected to grow to $180 billion by 2020. As consumer demand for clean labels increases, more brands are expected to follow the clean-labeling movement.

But 45 percent of U.S. consumers don’t know what a clean label is, according to a 2015 Canadian global study.

Ali Berg, a University of Georgia Cooperative Extension nutrition expert and assistant professor of foods and nutrition in the UGA College of Family and Consumer Sciences, says the majority of consumers are often confused by new trends in food marketing. Of course, “clean food” sounds good, but that doesn’t automatically make it a healthy choice.

“Butter might have a short label of only cream and salt, but that doesn’t mean it’s a great choice, nutritionally. Similarly, a bacon cheeseburger made from only organically raised and grass-fed animals with organic produce doesn’t have fewer calories,” Berg said. “Also, some ingredients that you might not recognize are really important for food safety, quality and freshness. I’ve seen consumers read an applesauce label and say they don’t know why it has ascorbic acid in it or what that is. When I tell them it’s vitamin C and it keeps the applesauce from browning, they usually are OK with it.”

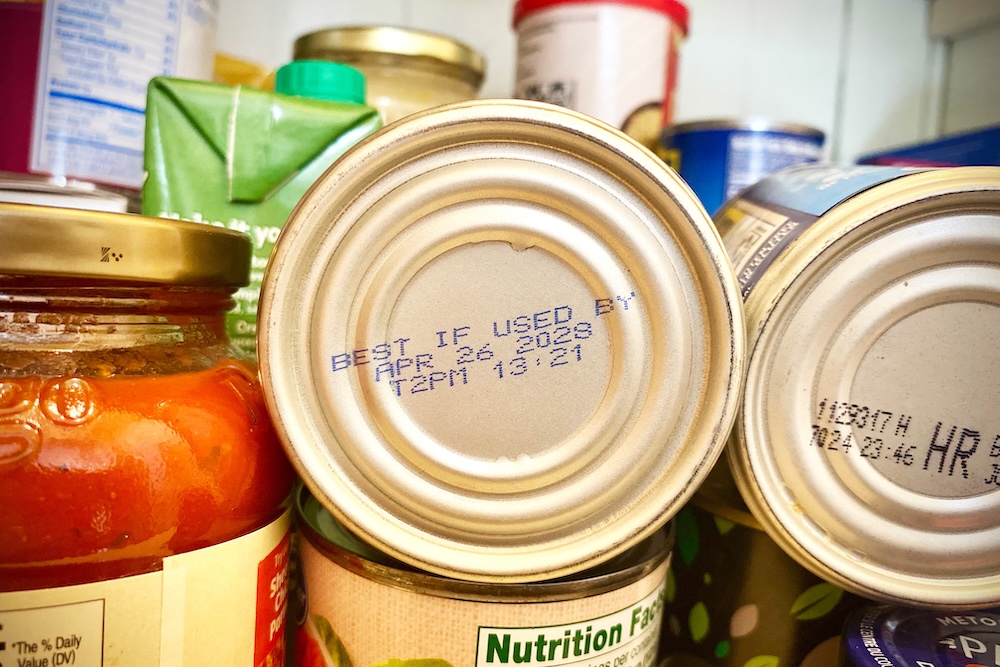

While simpler foods are often better for us, a clean label isn’t always superior. That said, Berg noted that many of the simplest foods, like fruits and vegetables, don’t come in boxes or cans at all. When they do, as in the case of apple slices or frozen vegetables, use the nutrition label to see if sugars or salt were added.

That being said, when consumers shop for packaged foods, they need to know what they’re being sold before they pay a premium price for something labeled “clean.”

Generally, a clean label emphasizes simplicity, transparency and minimal processing. It’s used to highlight the fact that the product includes ingredients with uncomplicated names that consumers recognize. There is currently no regulatory, legal or universal definition for a “clean label” or a “clean food.”

According to food science and business researchers, the Food and Drug Administration has no definition for the word “natural” at this time, and it’s currently seeking input on how to define this on food labels. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), which oversees meat and poultry labeling, does not have an official definition of “natural” either. For a meat or poultry product to have a “natural” claim, it must include a statement describing the term, such as “no artificial ingredients; minimally processed.”

For a product to have an “organic” label, the standards are different and mostly refer to how the food was produced. An organic product’s production must meet the strict standards of the National Organic Program (NOP), which is administered by the USDA. However, some compounds, such as potassium bicarbonate, ammonium bicarbonate and calcium hydroxide, are allowed on organic labels.

There is no formal definition of a “clean label,” so restaurants, retailers and food companies have developed their own definitions. Consumers should ask questions to find out what “clean” means in each situation.

More and more consumers want to know how their food was sourced and manufactured, and there is a consumer demand to pare down complicated ingredients that sound like chemical compounds. But where there’s consumer demand, there are always savvy marketers willing to take advantage of that demand. Without any regulations governing “clean food,” it’s up to consumers to read labels and understand what they’re getting.

For more research-based information on how to eat a healthier diet, see UGA Extension food publications at extension.uga.edu/publications.