Gummy stem blight can be a tough foe for watermelon farmers to tackle. With the ability to cause lesions on leaves and turn stems into gooey mush, the plant disease can cripple watermelon production.

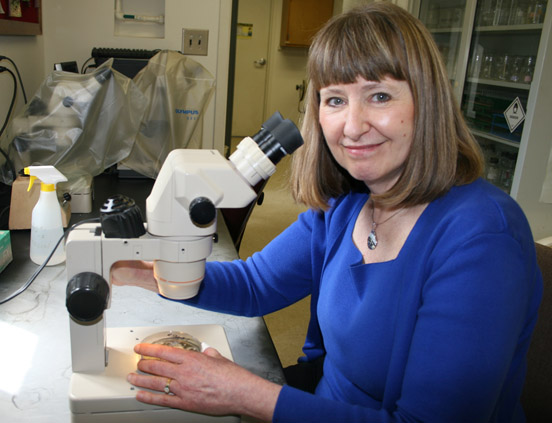

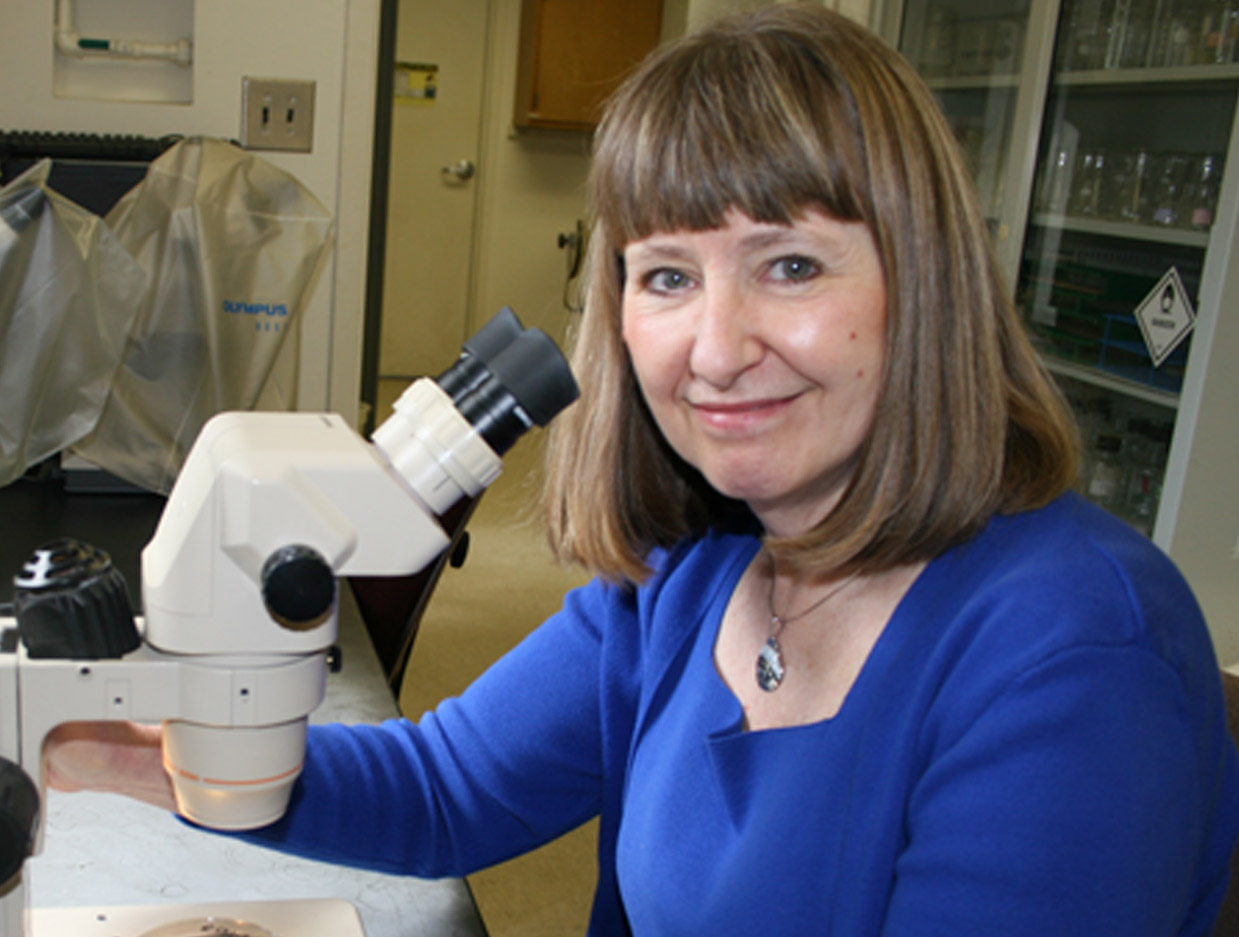

“It can wipe out an entire field. It can cause 100 percent losses,” University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences plant pathologist Katherine Stevenson said. “This pathogen loves warm, wet conditions. Like last year when we had a week of rain and it was 90 degrees, the gummy stem blight just took off. We had field plots of watermelons planted and it just wiped them out completely.”

Finding the right fungicide application is critical to the future of one of the state’s top vegetable crops. According to the 2011 Georgia Farm Gate Report, watermelons generated $98 million, considerably less than the $139 million in revenue tallied in 2009. The drop in value can be attributed to gummy stem blight’s impact, which Stevenson is trying to alleviate.

Gummy stem blight is caused by the fungus Didymella bryoniae and leads to losses for growers every watermelon season. The ideal scenario for Stevenson and watermelon farmers everywhere would be the development of disease-resistant watermelons, which is currently being researched in Athens.

“We don’t have any that are commercially available now. Basically all the watermelon cultivars that are grown are susceptible to gummy stem blight,” Stevenson said. “There are cultural practices that can help (treat diseases) but they won’t completely eliminate the problem. Still, fungicides are the most effective form of treatment.”

A member of the UGA faculty since 1992, Stevenson has been stationed on the Tifton campus for almost a decade. She works in epidemiology, the study of diseases and how they develop in populations. Stevenson studies disease development, how weather conditions affect whether a disease occurs and how rapidly it spreads, how diseases develop in space, how it spreads and how it’s dispersed. Currently, she’s focusing on fungicide resistance.

Fungicides are essential for farmers who hope to eliminate fungal problems within their crops like watermelons or pecans and peanuts. These fungi, if not treated successfully, can lead to destructive diseases like gummy stem blight or pecan scab.

“Most of the fungicides that are produced now have what’s called, ‘a single-site mode of action,’” Stevenson said. “They’re very specific for fungi. They’re made that way because they’re safer for you and me. If they only target one little enzyme in the fungus, they’re not as likely to affect humans or other non-target organisms.”

These fungicides bind with an enzyme that’s needed by a specific fungus, making it unable to function normally.

“What can happen is you can get one little mutation in the gene that codes for that enzyme and that mutation changes the conformation of the enzyme just enough so the fungicide can’t bind to it,” she said. “If the fungicide can’t bind to it, then it doesn’t work and the fungus keeps living and reproducing.”

Stevenson’s success depends largely on teamwork. She works closely with her UGA Extension counterparts like vegetable horticulturist David Langston to develop effective fungicide programs. Together they study chemicals that can be rotated to try to keep resistance from occurring. Langston will develop different treatments for different rotations, then Stevenson will sample each of those treatments to try to see any differences in the level of resistance. The objective is to try to discover which works best to keep resistance from happening.

For more information about UGA’s plant pathology program, see the website at plantpath.caes.uga.edu.