The current drought in Georgia has caused significant problems for farmers in central Georgia and other areas of the state, but a lack of impact on the state’s larger cities and drinking water supplies has kept it off most Georgians’ radar.

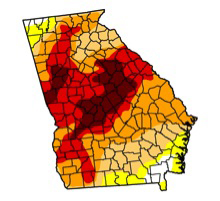

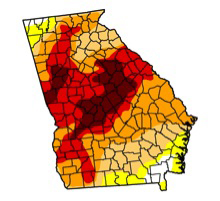

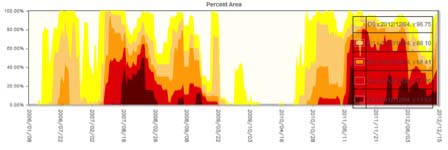

As of early December, about 14 percent of the state was experiencing exceptional drought, which is drought that is only expected to occur on the average every 50-100 years. This region was experiencing some level of drought during the entire 2012 growing season.

Rainfall early this week has provided some temporary short-term relief to dry areas in Georgia, particularly in the northern half of the state. However, this rain will provide only limited improvements in areas that have seen rainfall deficits as low as 20 inches below normal in 2012.

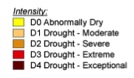

Drought is classified into four levels: moderate (D1), severe (D2), extreme (D3) and exceptional (D4) drought. A few areas in central Georgia have been experiencing extreme drought — the second most serious category of drought — continuously since May 2011.

While wetter weather this summer alleviated drought in some areas of the state, drier than normal conditions have since expanded due to a deficit of tropical rainfall at the end of the summer and a persistent high pressure system that has diverted storms away from the state.

Why so dry?

Normally, rainfall from tropical systems provides a significant percent of all the rain that falls on Georgia during the late summer and early fall months. However, this year Georgia was largely bypassed by tropical systems.

The coastal areas did see some rain from Tropical Storm Beryl in May, and Tropical Storm Debby dropped rain along the southern tier of counties in June. Hurricane Isaac initially looked like it would bring substantial rain to Georgia in late August, but instead came ashore to the west in Louisiana. A small piece of Isaac passed through Georgia from north to south as the storm broke apart, but brought only a limited amount of rain to the state.

This fall a strong high-pressure system steered rain-bearing systems away from the state and suppressed convective rain. The systems that would have usually brought rain to Georgia passed to the north of the state, resulting in a fall that was even drier than usual for the driest time of year.

More than 50 percent of the state received less than half its usual rainfall in September, October and November, causing stream flows to drop to near-record levels and expanding the areas affected by drought.

2007-2009 drought compared to the 2012 drought

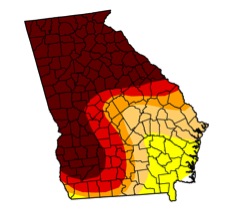

One of the differences between the current drought and the drought of 2007-2009 is the location of the areas affected by the drought. In 2007 the center of the worst drought was in northern Georgia, where it affected cities like Atlanta and Athens.

The extremely high temperatures associated with that fast-developing drought and concerns about water supply and water usage helped to raise public consciousness about the severity of the drought and generated increased media attention.

By comparison, the current drought has affected a smaller part of the state with less effect on water supplies.

Local and state utility and water managers took the lessons from the 2007-2009 drought to heart and have managed their water supplies more carefully. In addition, consumers have learned to use water more sparingly and demand has been lower in many water systems. The current drought has consequently impacted water supplies less severely than in the previous drought.

More of the state is being affected by drought now than at the worst periods of the 2007-2009 drought.

This drought has also been more persistent than the 2007-2009 drought, with parts of the state experiencing some level of drought for more than a year — versus nine months of continuous drought as seen in 2007-2009.

In the worst-hit areas, farmers have reported their farm ponds completely drying up — leaving nothing but cracked mud and fish bones behind — something they did not see in the 2007-2009 drought.

Groundwater levels in the lower Flint River basin are, in many cases, at or near record lows. Stream flows across the state have also been very low during the recent weeks except immediately after rain events.

Outlook for the winter and spring planting season

Over the winter months, drought usually decreases due to the lower water demands from dormant plants and the lower temperatures, which reduce evaporation from the soil. The rain and snow we get normally soaks into the ground and replenishes the soil moisture for the spring planting season. This is likely to happen regardless of how much precipitation we get over the winter. However, once the next growing season starts, these reserves of soil moisture could be quickly exhausted when plants break dormancy and evaporation increases in the warmer temperatures.

The outlook for winter precipitation is uncertain. Originally, an El Nino weather pattern was predicted to occur this winter. This was excellent news, since El Nino is usually associated with above normal rainfall across Georgia. However, the El Nino fizzled early, and now we are in neutral conditions — with neither an El Nino nor La Nina present to steer storms towards or away from Georgia.

In neutral conditions, we know that the state is equally likely to receive normal, below normal and normal amounts of precipitation. This is of concern because with the current dry conditions, below normal precipitation will make the drought worse, and even normal rainfall will only lead to moderate decreases in drought over the winter.

There is only a 33 percent chance of getting above normal rainfall based on statistics for neutral years. This means that spring soil moisture could be of critical concern to farmers, since germination and plant development depend on having adequate supplies of soil moisture.

Low stream flows and falling ground water levels, especially in the Flint River basin, could affect southwest Georgia farmers’ ability to irrigate their fields in the coming months.

Without a La Nina or El Nino weather patterns, predicting temperatures over the course of the winter is difficult. However, neutral conditions have been associated with more frequent cold outbreaks, which can lead to increased frost and freeze events.

Soil moisture helps insulate soil from extreme temperature changes, so Georgia’s currently dry soils may experience more extreme temperature changes in farmers’ fields and could result in increased damage to plants.

If you would like more information or would like to report drought impacts in your county, please contact Pam Knox, UGA agricultural climatologist, at 706-542-6067 or pknox@uga.edu.