Soybeans are critical to the U.S. economy. But the third largest crop in the nation has an enemy eating away at it, a fungus in the same family as the one that caused the infamous Irish Potato Famine.

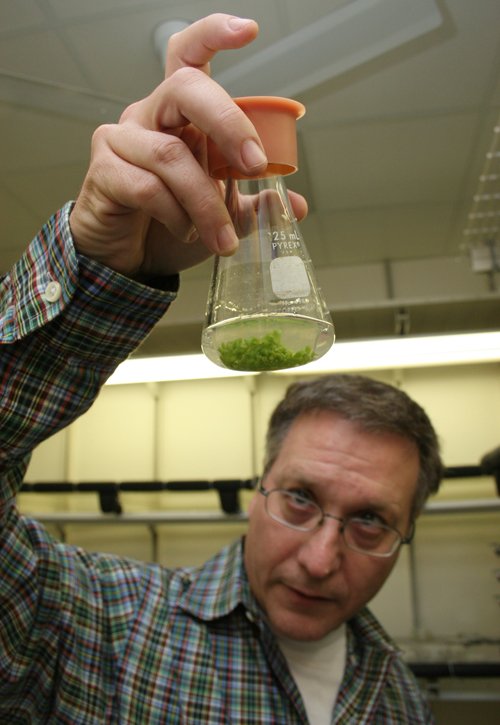

The fungus is called Phytophthora sojae. The University of Georgia and 17 other universities are part of a research project designed to find ways to stop it from destroying soybeans.

Phytophthora “is a big problem,” said Wayne Parrott, the lead UGA College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences researcher on the project. “The thought is that we lose about half a billion dollars to this pathogen in soybean alone. As we’ve been going toward more no-till, it favors the fungus, and the disease-resistant genes that are there are getting old and breaking down over time.”

According to the United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, farmers planted 77.4 million acres of soybeans last year and harvested 3.3 million bushels valued at $38.6 billion.

Parrott, a crop and soil sciences professor, is studying soybean genes to see if there is a way to engineer longer-lasting economical control of the fungus. He’s looking at two methods.

The first is based on turning off a protein in the plant that the fungus needs to be pathogenic, “altering the plant a little bit so that the fungus doesn’t recognize soybean as a host,” he said. “Soybeans without intention are signaling to the fungus, ‘hey, I’m a soybean. Come get me.’”

The second approach is based on research UGA scientists have done to keep nematodes, a type of worm, from invading various other crops.

“The idea is that you have the plant turn off the genes in the nematode that the nematode needs to parasitize the plant,” Parrott said. “We’re going to try to get the plant to turn off the genes that the Phytophthora needs to infect the plant. We’re hoping that one of those two approaches, or both combined, will give an affective solution.”

More than genes

Parrott is working under a five-year, $9.28 million grant awarded by the USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. UGA’s portion is $630,500. Virginia Tech’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences is leading the research. The goal of the collaborative project is to not only find genes that would keep soybeans safer, but to find other ways to help farmers in the field.

“The approach of the grant is very holistic,” he said. “It’s management practices and things you can do quickly and better and involves diagnostic kits for farmers so that they know what’s going on before they have to take control measures. There’s a very heavy Extension component to make sure that all this gets out to the farmers.”

Many of the states on the grant are from the Midwest because most of the nation’s soybeans are grown there. But Georgia farmers grew 500,000 acres of soybeans in 2009, worth $168.4 million.

“If you eat chicken or you eat pork, you’ve eaten soybeans,” he said. “That’s the basis for the poultry and the pork industry in the U.S. If you’ve had vegetable oil, you’ve eaten soybeans. Some people say that soybean is the No. 1 source of calories in the U.S. diet.”

Trade-off

Because farmers have moved toward no-till on their land, which is a more environmentally friendly practice, it makes it easier for the Phytophthora to survive.

“The thing about ag is that everything is a trade-off,” Parrott said. With no-till “you use less gasoline, you have less erosion, it’s more economical and you get more soil organic matter. And all of those are good things, but the trade-off is some diseases can live out there.”