Foodborne illness is a leading cause of disease in the United States. And, now more than ever, it’s a leading subject of headlines. Where food comes from now and how those illnesses are reported and tracked could be the reason why people are paying more attention, say University of Georgia food experts.

In the U.S., there are 76 million food-related illnesses annually. According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 325,000 people are hospitalized and 5,000 die from foodborne illnesses.

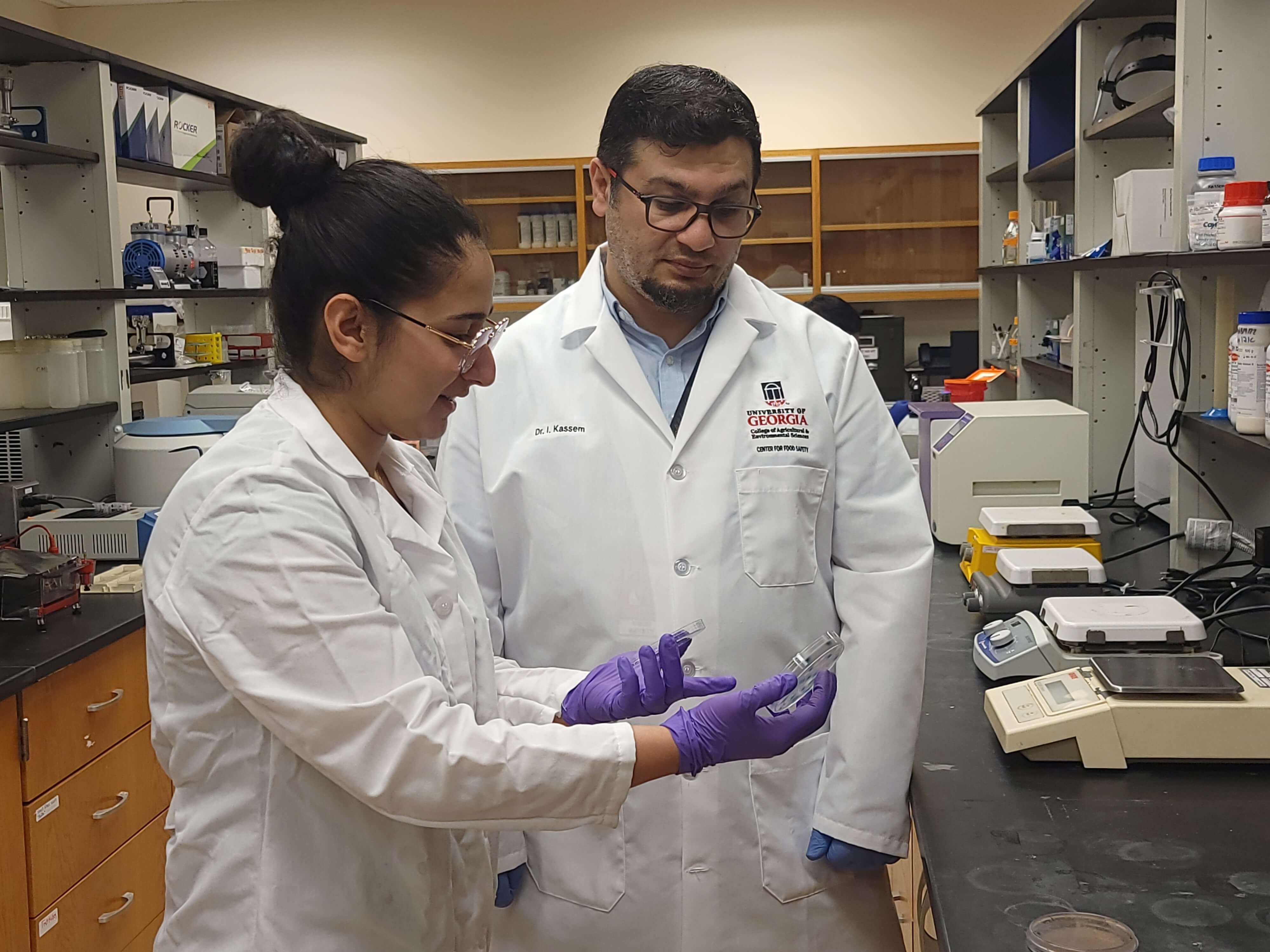

Foodborne illnesses appear to be increasing and reported outbreaks getting larger, said Walid Alali, an assistant professor of food safety at the UGA Center for Food Safety.

“We know more as we have improved surveillance systems and people are reporting more than ever before,” said Alali, speaking at the UGA College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences’ 2010 Georgia Ag Forecast in Gainesville, Ga., Jan. 26. “People are more aware of food sickness, and they report illness and what they consume. It might not be that more people are getting sick. It might be that we have better reporting, analysis and interpretation of foodborne data mechanisms in place.”

Using a system called PulseNet, the CDC is now more able to quickly track and respond to such illnesses and outbreaks. The molecular foodborne pathogen surveillance system, debuted in 1995. When a sickness happens, state health departments send bacterial DNA information to the database where information from across the U.S. is monitored for outbreaks.

“Because of the improved DNA fingerprinting methods, you are able to identify clusters of similar bacteria from infected people and to detect the food source of all these bacteria,” Alali said.

“We have an increased ability to detect connected outbreaks from all over the country,” said Elizabeth Andress, a UGA Cooperative Extension food safety specialist attending the meeting. “We can DNA fingerprint the particular bacteria associated either from the food or the person that got sick. And because we can do that, we can make these links, and we can show these multi-state outbreaks more than we ever could before.”

Most foodborne illness outbreaks used to be localized and caused by a common food source, such as at a community event or social gathering. But things have changed, Andress said.

“Technologies for reporting food illnesses are changing as well as the food vehicles for outbreaks,” she said. “We still see outbreaks from mistakes people make like undercooking meat or not holding foods at the right temperatures, but in addition in the past few years we’ve had these widespread national outbreaks from either processed foods or raw commodities distributed all around the country.”

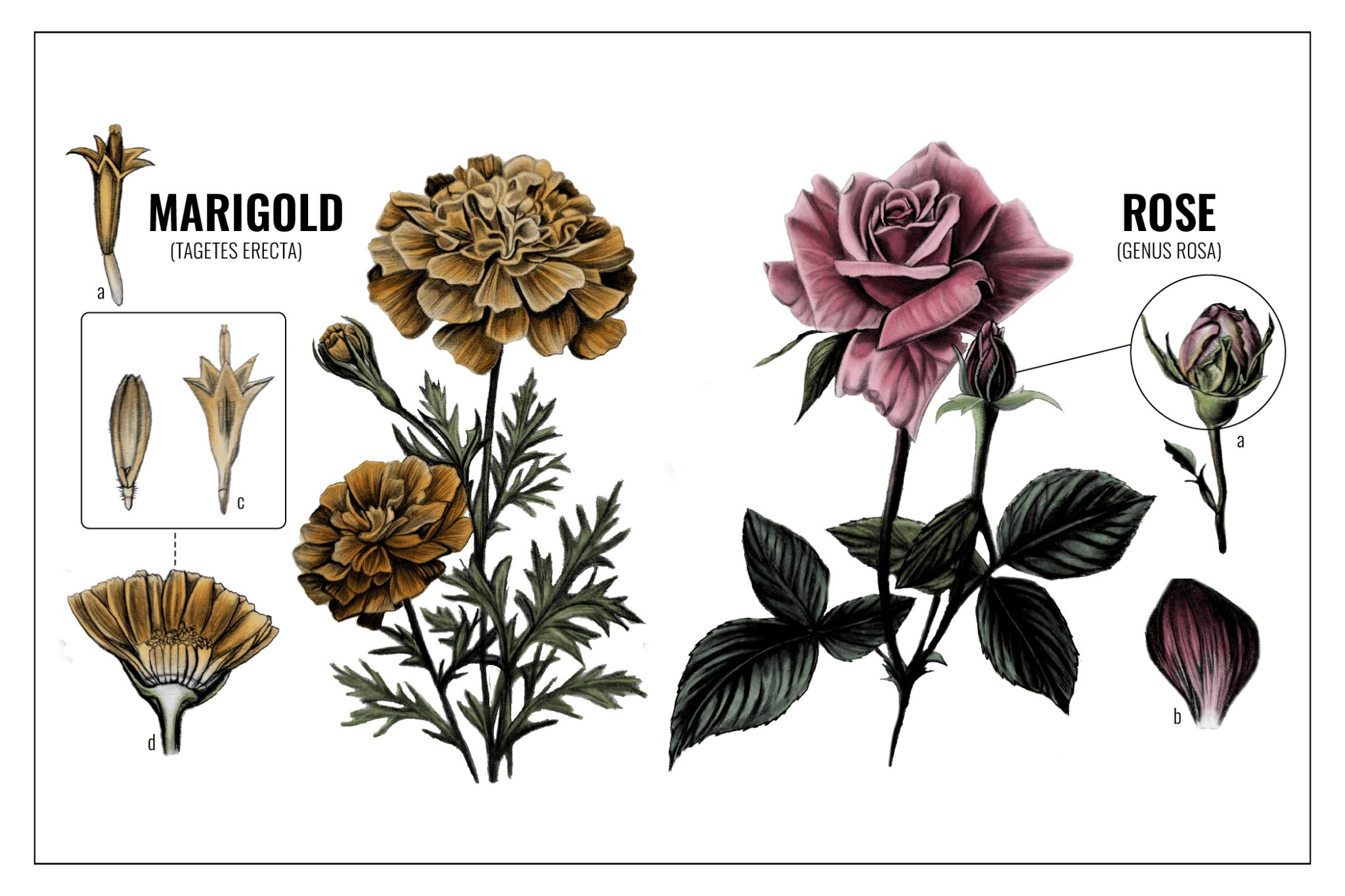

Hundreds of illnesses from contaminated spinach, lettuce, peppers, tomatoes and even peanut butter have made recent U.S. headlines. Other reports tell of tainted shellfish, pet food and a variety of foods and food ingredients imported from other countries.

Nearly 15 percent of the food Americans eat is imported from other countries, mostly from Canada, Mexico and China. This may sound like a small percentage, but it represents 80 percent of the seafood, 45 percent of the fresh fruit and 16 percent of the vegetables consumed in the U.S. Less than 1 percent of this food is visually inspected by the Food and Drug Administration. Less than .5 percent is currently inspected for pathogens.

According to a national survey, Alali said, 90 percent of U.S. consumers are somewhat comfortable to very comfortable with the safety of U.S.-grown food. Only 42 percent feel the same way about food grown outside the U.S.