.jpg)

While we had an early start to the growing season, it was followed by colder conditions in March that slowed things down quite a bit. Since that time, we have seen periods of very warm weather alternating with much cooler conditions. As soil temperatures rise and fall, it has been tough for farmers to know when to plant. Wet conditions have also been an issue in some areas.

The current cool weather is expected to stick around until early May, but after that the extended outlook shows a likely return to warmer-than-normal conditions for much of the growing season. We expect there will be occasional cooler periods, but the warmer conditions should help crops catch up on growing degree days and most should start developing at a more rapid pace than they are right now. Rainfall has been quite good for the year to date, especially in northern Georgia, although it has been drier in the southern half of the state. The extended forecasts at the moment do not indicate any extended period of very dry conditions, so I am hopeful that we may escape a big drought this summer in spite of the warmer-than-normal temperatures.

El Niño conditions

The big player in the weather the rest of this growing season and next winter is the rapidly developing El Niño. La Niña left us a month or so ago and we are now in neutral conditions, hovering between La Niña and El Niño. But there is a rapidly growing warm pool in the eastern Pacific Ocean that is a sign that El Niño will be declared in the next few months. The odds currently put our chances of a strong El Niño by fall at 40%, with an almost 70% chance of at least a moderate El Niño and only a 10% chance of no El Niño at all, so it is safe to say that we need to prepare for it now. El Niño does not have a lot of impacts on Georgia in the summer months, but by fall it will start to impact conditions here in Georgia and surrounding areas.

The statistics and longest-range climate models suggest that by November we could see typical rainy El Niño conditions occurring over southern Georgia and Alabama down into Florida as well as up the East Coast. Some models have wet conditions starting as early as October. For farmers, this means that you will not necessarily be able to count on a dry fall for harvesting. David Zierden, the state climatologist for Florida, says that you may wish to plant varieties that will mature more quickly so you can harvest before the wet conditions really get entrenched later in the fall. If your crops are already in, then you will want to be watching the weather forecasts carefully this fall to take advantage of any dry windows to get in the fields and take care of the harvest. This is likely not going to be a year where you can leave crops out in the field without taking a hit on quality and the ability to harvest late due to potentially wet weather and field conditions.

We also usually experience cooler-than-normal temperatures in El Niño winters. This is not necessarily because we are getting more air from the Arctic, but because the cloudy conditions associated with the persistent storm track across the region hold daytime temperatures down. This means that it should be easier for fruit farmers to get enough winter chill for their crops. Being in an El Niño does not tell us much about the potential for a late spring frost, although if it swings back to neutral conditions by spring, the chances go up a bit. Much too early to know about something almost a year from now, though.

Potential for tropical storms

The other consideration for an El Niño is its impact on the Atlantic tropical season. Generally, when an El Niño is in place, the strong jet stream aloft makes it hard for tropical storms to organize, so we typically have fewer named storms in El Niño years. But that does not mean that we won’t see any impacts. Remember, Hurricane Andrew developed at the end of an El Niño in 1992 and Hurricane Michael formed as the last El Niño episode was starting in fall 2018. It just depends where the storms go, and that is not predictable on a seasonal basis. Since the Gulf of Mexico has sea-surface temperatures that are quite a bit warmer than normal for this time of year, I would not be surprised if we saw an early start to the tropical season with storms coming in from the Gulf. Some may develop quickly due to the warm water. Later in the summer and into fall, when El Niño is stronger, the number of storms in what is usually the most active part of the Atlantic tropical season may be reduced. As ocean temperatures continue to rise, storm development is more likely, so that may counteract the lower tendency of tropical storm numbers in El Niño years.

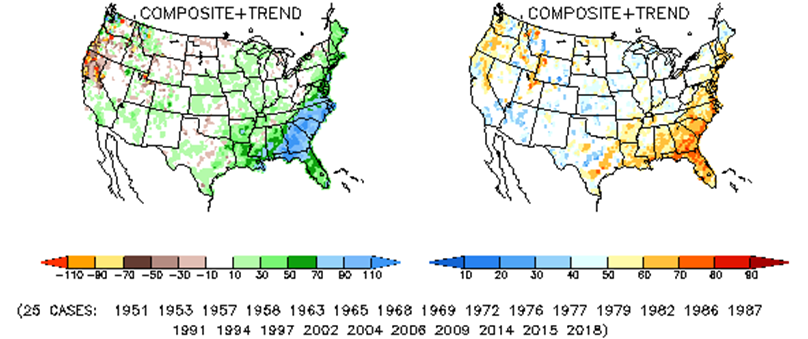

The embedded maps from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Climate Prediction Center show the likely above-normal precipitation anomaly for November through January in an El Niño fall and winter on the left and the frequency at which this anomaly has happened in past El Niño episodes on the right. The likelihood of a wet November through January across most of the Southeast is quite high, with the highest probability occurring in southern Georgia and coastal South Carolina plus most of northern Florida.