Inheriting a virus may sound like an undesirable bequest, but for certain insects, the phenomenon of beneficial virus inheritance is key to their survival.

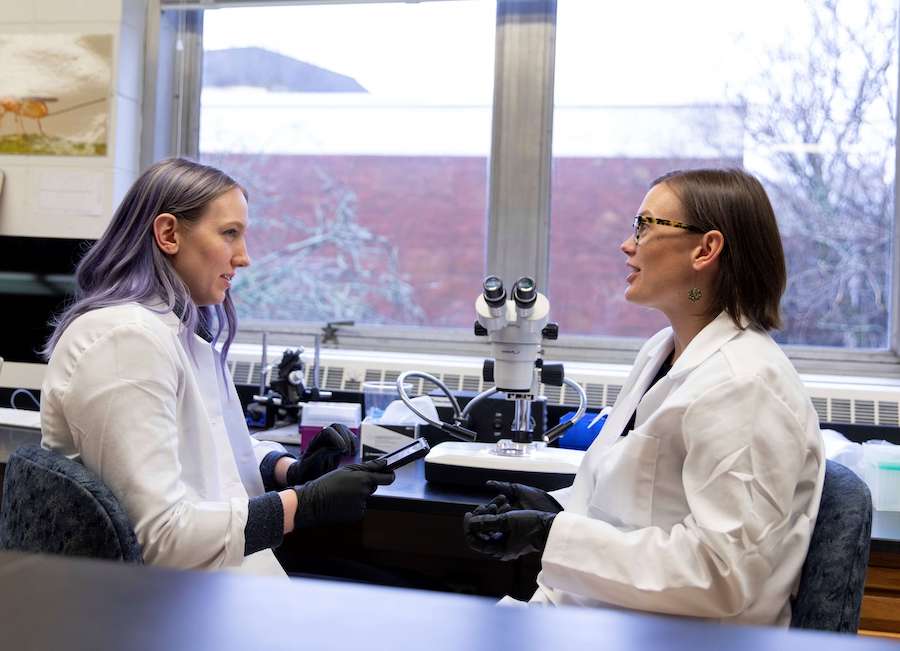

In the case of certain parasitoid wasps, viruses not only help these beneficial insects survive, they eliminate many agricultural pests in the process, according to a recent paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) by recent University of Georgia entomology doctoral graduate Kelsey Coffman and co-authors entomology Associate Professor Gaelen Burke and entomology researcher Quinn Hankinson.

“In this study, we identified a unique way that one of these mutualistic viruses is transmitted among parasitoid wasps that it benefits,” said Coffman, who now works as a postdoctoral researcher for the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“In the end, what we have found is a highly effective way for this virus to be passed around between wasps in a population, but unlike pathogenic viruses, this is a really good thing for wasps to have,” said Coffman.

Most of the small number of known beneficial viruses have been identified within parasitoid wasps, which develop by living within and feeding off other insects as parasites. These tiny, non-stinging wasps are some of the most beneficial insects in the garden and are known to parasitize, or kill, many species of pests. Although there are many different species of parasitic wasps, they all work by preying upon one or more pest insects.

“These symbiotic viruses are not studied nearly as much as pathogenic viruses, but it is likely that they play very important roles in the biology and evolution of their hosts,” Coffman said, explaining the origin of her research.

According to Coffman’s research, female wasps intentionally spread a specific virus to their young by injecting the virus into a host insect while laying eggs in the unsuspecting arthropod. The virus is thought to work within the host like a biological weapon to subdue and defeat host defenses that would work to kill the wasps’ offspring as they develop.

Here's how it works: Using fruit fly larvae as her host, the female Diachasmimorpha longicaudata injects virus particles from her venom gland while laying her eggs inside the larvae. Once inside the fly larvae, the virus replicates and spreads throughout the fly body as it develops.

As the wasp eggs develop, the wasp larvae are in constant contact with the virus particles while feeding on the fly from the inside out. As a result, the virus particles that remain stuck to the outside of the wasp as it develops are eventually internalized during the formation of the new wasp’s venom gland in female offspring.

“This virus is using a form of post-hatch transmission to get passed on from mother to daughter, a process which we haven’t yet seen for a beneficial virus,” said Coffman of the groundbreaking research.

“This work is really important because it helps us work out how these viruses have changed from the pathogenic kind to being beneficial for the wasps that the viruses replicate in,” said Burke, who directed Coffman’s graduate research in the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences.

The knowledge gained from the research Coffman conducted has ramifications for both agriculture and society as researchers work to comprehend more about how viruses function molecularly and maneuver to survive.

“Since the host insects of some of these wasps are major agricultural pests, the use of parasitoid wasps is therefore a natural and sustainable way for humans to suppress pest populations,” Coffman explained. “If we can understand the molecular dynamics that these viruses utilize to cause problems for pest insects, we could potentially exploit these naturally occurring virus-derived strategies for future pest-control innovations.”

Perhaps most exciting for researchers is that this specific new knowledge helps bring the picture of virus behavior into clearer focus.

“Understanding how beneficial viruses are transmitted is one piece of the puzzle for all the ways that viruses, good and bad, shape life on Earth,” Coffman said.