It is not difficult to find somebody talking about methane these days. Simply turn on the TV, open your computers to your news affiliate of choice or log into any social media platform.

Over and over we have been told that methane is a potent greenhouse gas, it contributes to global warming, and since ruminants (i.e., cattle) produce methane, they are destroying the world.

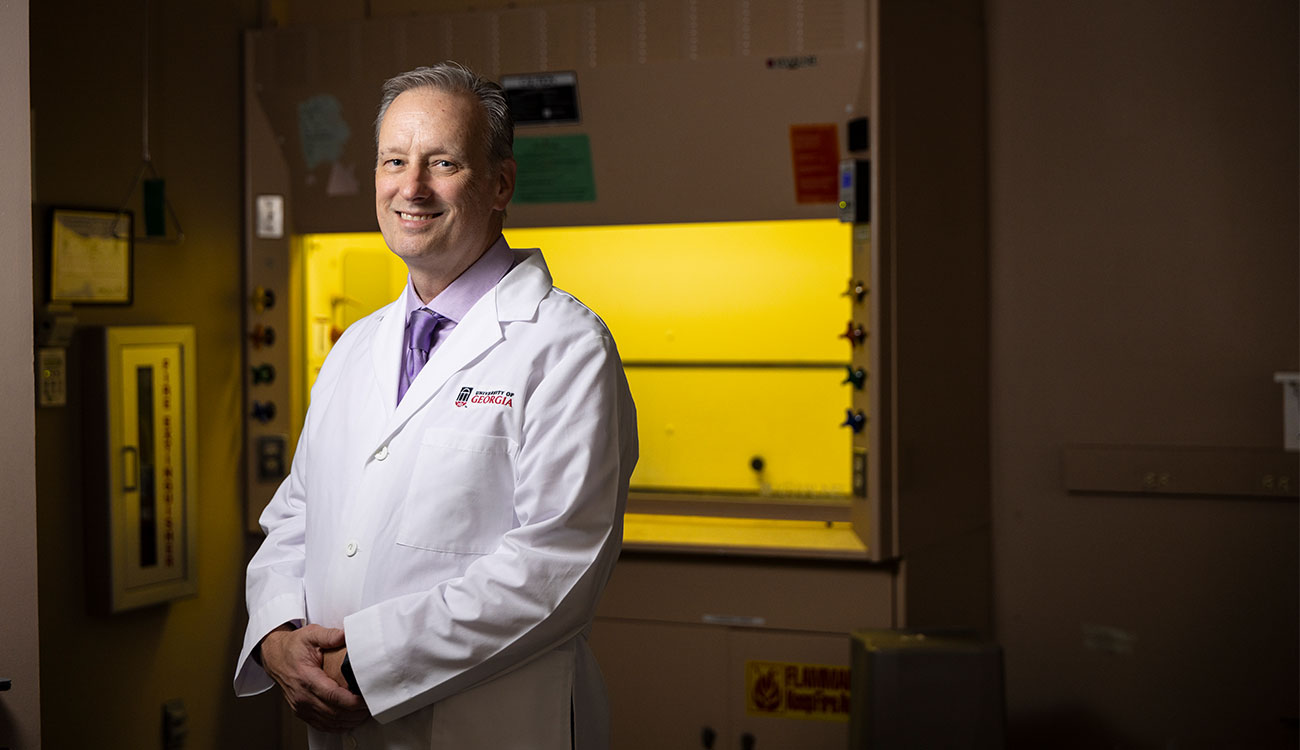

I am here to tell you that all of that is true, other than the last bit about cows destroying the world. On the contrary, cattle have a role in actually cooling the Earth’s atmosphere.

It is true that cattle produce methane — the average beef cow can produce between 0.1 to 0.2 pounds of methane every day. This is a natural process that allows the animal to control the pH of their rumen by removing hydrogen, an element that impacts acidity.

Methane is a very potent greenhouse gas and we do need to do our part as humans to try to reduce the amount of methane produced. However, unlike carbon dioxide (CO2) which is in the atmosphere for approximately 1,000 years, methane only has an atmospheric lifespan of 10 years, after which methane is converted to CO2.

The other element that makes up methane is carbon. Let’s consider where this carbon is coming from — the cow's diet, whether that be forage, supplement or a total mixed ration. For the most part, our cattle are consuming plants, either as forage, grain or byproducts.

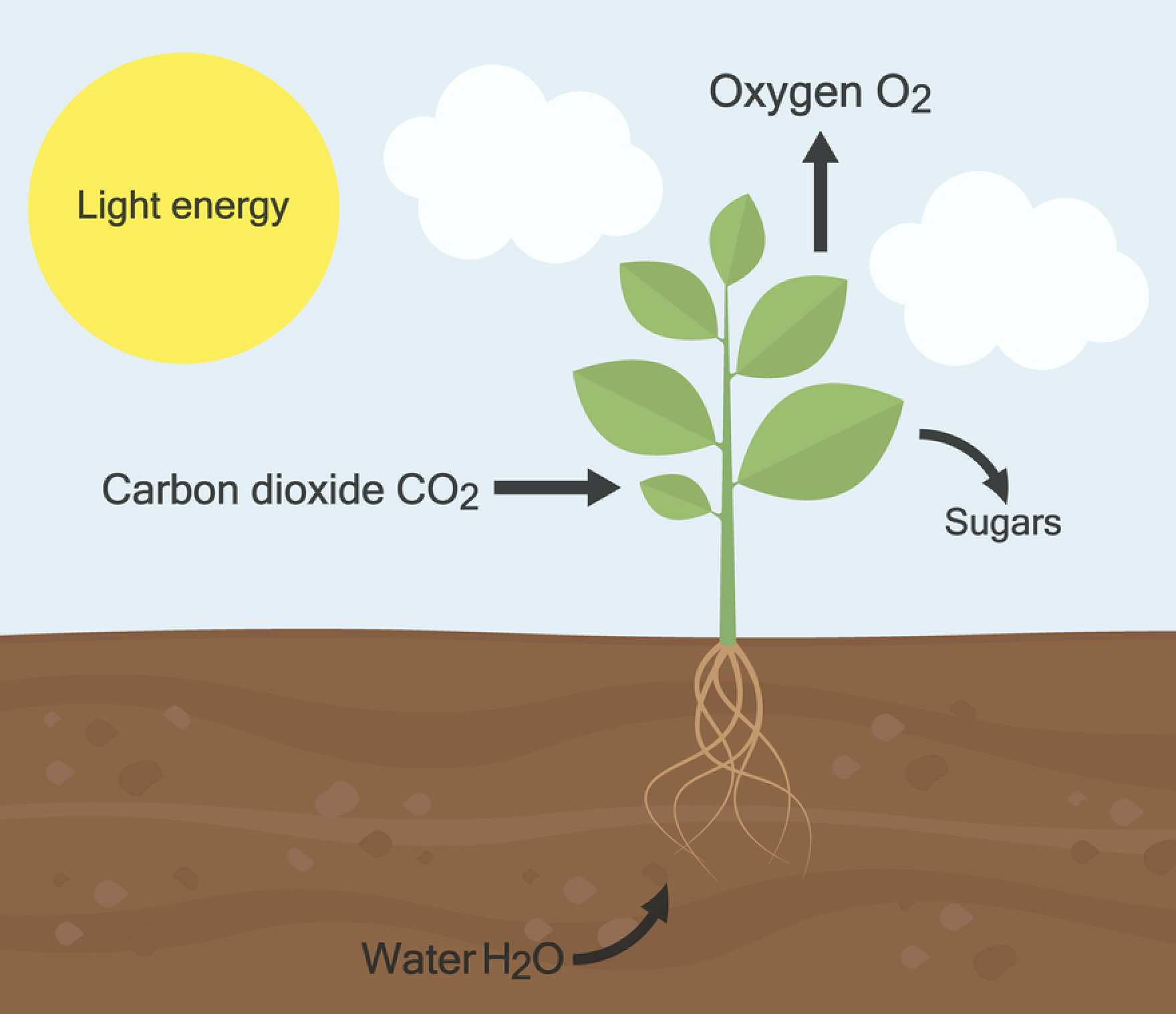

Now, let’s think back to fifth-grade science class and remember how plants grow.

Through a process called photosynthesis, plants pull CO2 from the atmosphere and peel off the oxygen (O2), using the carbon to produce energy for plant growth. This means that the methane produced from the rumen of cattle is formed from CO2 that could have previously been methane from the rumen of a grazing beef cow. This is the cycle of biogenic methane — methane that is produced by a living organism.

If we consider that the methane produced from the U.S. beef herd is biogenic and that this carbon is consistently being recycled through the system via grasslands and grain, the story we should be hearing is that cattle are not actually a negative source of greenhouse gases, but instead can actually act as source of carbon sequestration and short-term global cooling.

Today, if the global cattle herd does not grow in number of head, the amount of carbon released (i.e., methane) and sequestered (i.e., CO2 taken into soils and plants) is in balance. This is great news! What is even better news is that if we utilize novel technologies, such as feed additives, we have the opportunity to release less methane, which would lead to short-term cooling.

As producers, many may ask the obvious question, “If we are currently not significantly contributing to global warming with our cows, why would I want to spend more money to reduce methane?”

The answer to that is efficiency. When cattle produce methane, they do that at a cost and that cost is energy. Approximately 2 to 12% of the energy consumed by cattle is lost as methane, with cattle consuming forage-based diets producing three to four times more methane than their grain-fed counterparts. Therefore, by mitigating the release of methane from ruminants, the opportunity arises for that carbon to go into meat, milk or fiber production.

It is important for us to consider these aspects of methane production. It is easy for many of us to scoff every time we hear someone speak about the methane produced by cattle, but maybe it is time for us to consider that the story we need to be telling is that we have the ability to cool the planet with cattle while saving on our feed bills.