Following the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference, also known as COP26, which concluded Nov. 12, global leaders have committed to supporting and implementing actionable climate change measures.

Closer to home, the Drawdown Georgia project is a multi-institution, multidisciplinary effort to accelerate progress toward net zero greenhouse gas emissions in the state. The state group was inspired by Project Drawdown, a nonprofit organization “that seeks to help the world reach ‘drawdown’ — the future point in time when levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere stop climbing and start to steadily decline.”

Agriculture and climate

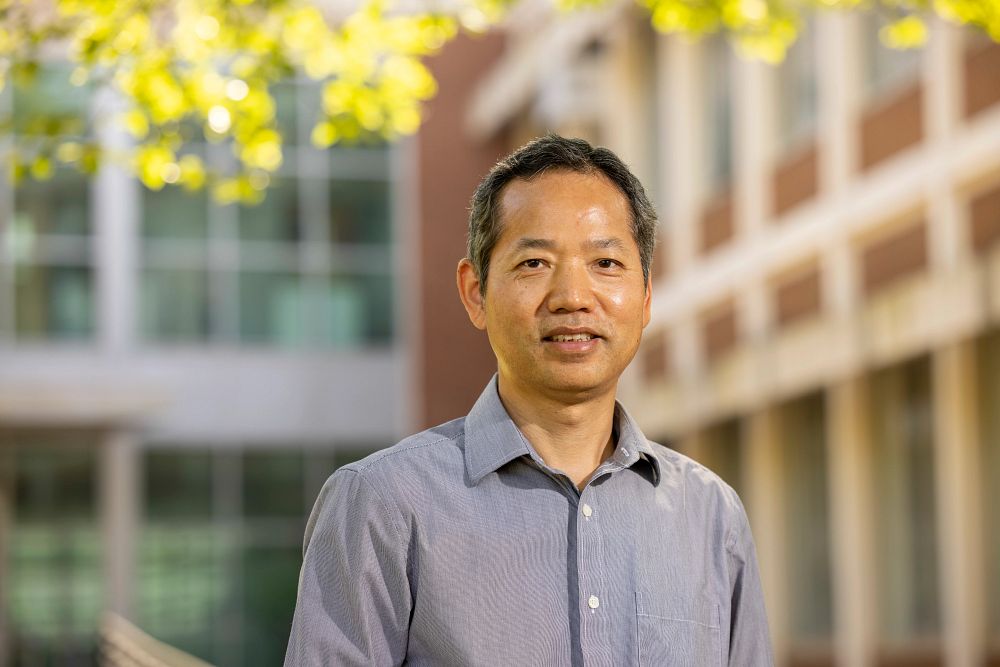

Sudhagar Mani, an adjunct professor in the University of Georgia’s Department of Food Science and Technology at the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences (CAES) and a professor in the UGA College of Engineering, served as a working group lead of the food and agriculture system for phase one of Drawdown Georgia, which concluded in May. The objective of phase one was to filter the 100 most substantive solutions from Project Drawdown through the lens of Georgia’s economy and identify carbon-reduction technologies and practices across a range of sectors that are most suitable for adoption in Georgia.

“Food and the agriculture system are a predominant sector in the global Project Drawdown. I think the food and agriculture system has the largest potential to reduce carbon and greenhouse gas emissions,” said Mani, whose background is in agricultural, dairy and food engineering, as well as chemical and biological engineering. “I have been doing some of the life-cycle analysis for carbon reduction for energy systems, essentially using bioenergy systems from crops that could be grown on agricultural lands and how we can utilize agricultural residues (such as cotton stalks and peanut hulls) for energy.”

Throughout the first phase of the project, Mani and other experts with Drawdown Georgia worked to identify the most meaningful solutions for the state, including existing, affordable technologies that could have a significant impact on carbon reduction while offering benefits such as job growth, improving air and water quality and protecting public health.

“Food waste reduction is a top-tier solution both at the global scale and in the United States,” Mani said. “There are several estimates, including from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, that about 55 million tons of food are being wasted every year. Although a fraction of the food waste is diverted to anaerobic digestion and composting facilities, a major fraction of the food waste including other organic wastes goes into landfills.”

Crunching the numbers

Now, in the second phase of Drawdown Georgia, working groups oriented by sector — including electricity, transportation, forestry, and food and agriculture — are gathering the information needed to demonstrate the baseline of carbon emissions in each county in Georgia.

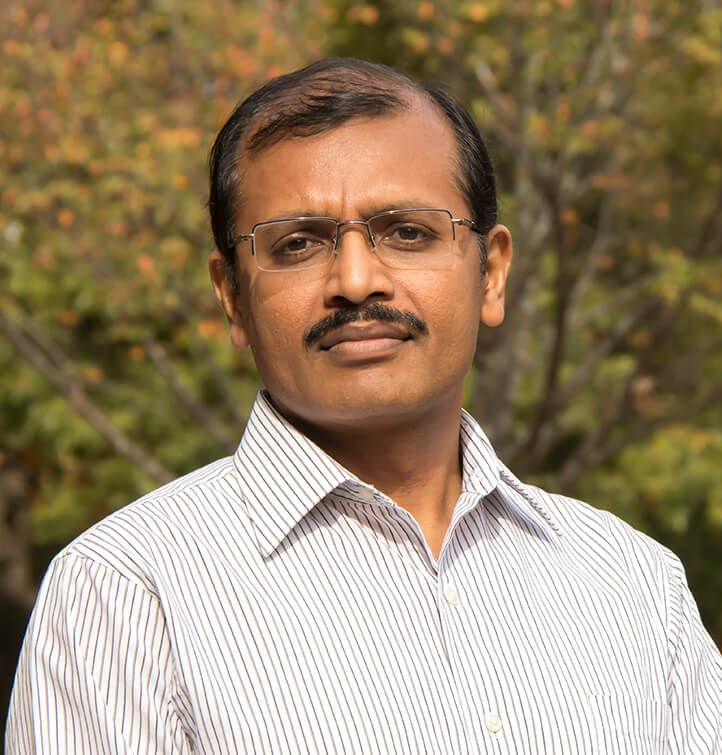

Jeff Mullen, an associate professor in the Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics at CAES, is working with William Drummond, associate director of the Georgia Tech Center for Geographic Information Systems, to analyze statewide data on emissions and food waste.

“Ideally what we want to do is track how emissions change at the county level throughout the 2020s, leading up to 2030, based on the actions taken to reduce carbon emissions in the state, broken down by each of these sectors,” Mullen said.

Drummond is gathering the baseline data for 2020 emissions and developing the methodology for year-by-year emissions tracking, while Mullen focuses on the state’s composting capacity, one of the solutions put forward in phase one.

On campus, Mullen and his team will do a cost comparison analysis looking at the price of using petroleum-based food service items against the cost of switching to compostable products at the UGA Center for Continuing Education & Hotel. Statewide, the team is working with public school systems in Georgia to calculate what they are spending on food service and delivery activities and how that would compare to the cost of adopting compostable products and composting systems.

A graduate student on the team is currently researching information on federal, state and local subsidies — usually in the form of tax breaks for oil exploration, well establishment and refinement — that lower the costs of producing petroleum-based products versus compostable products that do not receive the same benefits.

“That favorable write-off lowers the initial cost for extracting oil, which carries through the whole production line, lowering the end cost of the petroleum-based products,” Mullen said. “We want to see what would happen if we provided the same tax breaks to producers of compostable products or if we took those tax breaks away from producers of petroleum-based products. We want to see what would happen if there were a more level playing field across these areas.”

Reclaiming waste

The team is also creating a statewide map of current composting facilities in Georgia that will include information on capacity, types of materials accepted, and tipping costs for materials brought for composting to compare with the current waste management costs of public school systems in the state.

“Comparing the costs of buying the different materials and the cost to dispose of materials will help to determine if composting is more or less expensive,” Mullen said. “It is our expectation that composting will be more expensive, but by establishing a composting infrastructure throughout the state, we may be able to reduce costs to such point that that they would be competitive with the current systems.”

The phase two analysis could lead to expanding capacity at existing composting sites and locating new potential commercial composting sites throughout the state, he added. The project will include a transportation cost study comparing the current costs of waste disposal with the potential costs of instituting composting systems.

“Right now we need the information on what the existing throughput is from these systems. How much stuff do we need to get rid of? And how much will it cost to take waste from the schools to composting sites compared to taking it from the schools to landfills?” Mullen said.

The project will also consider the feasibility of establishing composting sites at the “point of consumption.”

“A middle school or a high school might have a school garden, and that could present the possibility of establishing a composting area on school grounds to eliminate disposal costs and provide some input for the school’s garden or groundskeeping activities,” Mullen said.

Encouraging institutional change

The next part of the project involves performing life-cycle analysis comparing the carbon emissions for current non-compostable food waste streams to potential compostable food waste streams, including all factors from packaging to transportation and other costs.

“If you have 100% compostables coming out of a food service facility, it all goes in one direction, to a compost facility. If you have no compostables, or you don’t separate them, then it is all going in another direction, to the landfill. Then there is the possibility of separating those two out and having two different disposal streams,” Mullen said. “That is what phase two is all about, mapping out the food waste stream with the public schools to determine how much is coming through the food system and how much is compostable versus how much isn’t.”

While some waste of inedible portions of food is unavoidable, improved education on composting and municipal composting programs could help mitigate a great deal of waste. Mani lives in Athens-Clarke County, where the municipal government now offers a drop-off service for compostable materials, but there is still not widespread availability of large, commercial composting facilities throughout the state.

“We need to increase that capacity. We have 159 counties in the state of Georgia and every county should have at least one public composting facility that can handle a lot of these wastes generated in their counties. Then that material should be composted and sent back to our agricultural land to enhance and regenerate our agricultural systems,” he said.

It is estimated that tree prunings and other organic yard waste account for 2 million tons of discarded material per year in Georgia, the majority of which is not composted. Like community gardens, Mani suggested neighborhoods or communities could adopt a community-composting program and educate members on proper composting.

“Corporations and businesses can adapt composting as part of the business cycle. UGA is a good example of composting with facilities at the university's bioconversion center, and we could be a role model for other institutions to adapt. We have about 52 four-year colleges and universities in the state of Georgia and each one of them should have at least one or two composting facilities. Every county has a public school system, and each system should have at least one,” Mani added.

Mullen is also interested in the social and educational impact of instituting composting systems in public schools.

“I think it is fascinating to consider starting this at the public school system level. If it becomes part of the culture of the school, it could become part of the routine of these students lives long after they have graduated,” Mullen added. “It is at least something they will think about daily. Even if they can’t do it at every turn, they are aware and familiar and comfortable with it. Our goal is ultimately to divert as much waste out of landfills as we can.”

Work on phase two of the Drawdown Georgia projects is scheduled to be completed in March 2022. Plans for phase three of the project, which would involve implementing researched solutions, depends on future funding of the initiative. Funding for the project has been provided by the Ray C. Anderson Foundation.

Incorporating thoughtful practices in our everyday lives is a small step toward making a larger difference.

“Food is a basic need of our life. We cannot ignore it, or not think about our food and where it is coming from. There is a certain level of responsibility every human needs to take,” Mani said. “We really should have institutional change, but we need to have a combination of solutions to really address the ultimate goal.”