Faced with the complex problems of hunger, poverty, public health, inequality, clean water, climate change and other global crises, it is easy to become overwhelmed. But solutions and a framework to achieving them are within reach if the world’s governments are willing to take the necessary steps.

This was a key message communicated by Ismahane Elouafi, the first chief scientist of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations (U.N.), during the 2021 D.W. Brooks Lecture hosted by the University of Georgia’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences Nov. 2.

Framework for the future

Adopted by the U.N. in 2015, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a framework for partnership between all of the world’s countries to address the major issues facing humanity, including accelerating the transformation of the world’s agri-food systems through the equitable application of science, technology and innovation, the topic of Elouafi’s lecture.

Calling 2021 “a year of transformation,” Elouafi expressed optimism that the world’s countries can come together to optimize the world’s agri-food system to achieve the U.N.’s agenda of meeting all SDGs by 2030 despite setbacks experienced before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Held in September, the first U.N. Food System Summit was “a golden opportunity for us to really bring together all these actors along the agri-food system,” Elouafi said.

“We have about 4.5 billion people that are employed or their livelihood is connected to the agri-food system … and we have those huge ambitious targets that all of our countries signed up for in 2015,” she said. “If we want to solve it, we have to have the bigger picture. We have to bring in not only ministers of agriculture, but ministers of water, ministers of health, ministers of infrastructure, ministers of finance, because it's beyond just the production cycle.”

Two dedicated “science days” were organized by Elouafi and other members of the scientific committee at the summit, with the objective to assess the challenges confronting the global food system and share science-based evidence and options “to explore the frontiers of science to give hope that there are new technologies, new ways that might allow us to do better, be more efficient, be more resilient and sustainable in our agri-food systems,” she said.

Actionable solutions

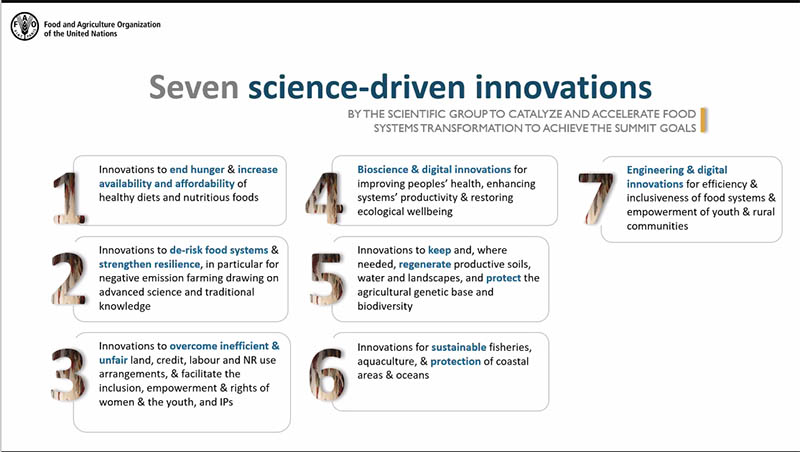

The work of the scientific committee was compiled into a strategic report that draws on FAO’s comprehensive food-system action framework that relies on four “betters” — better production, better nutrition, better environment and a better life — and seven science-driven innovations “that are very important if we are to design an agri-food system that is better for people, better for the planet and better for prosperity.”

The seven innovations include creating engineering and digital innovations to improve agricultural practices as well as human health by enhancing system productivity, restoring ecological well-being, protecting the agricultural genetic base and biodiversity, improving the efficiency and inclusiveness of food systems, and empowering rural communities.

Harnessing different sectors to address each of the SDGs will benefit the others through inherent linkages, such as between ending poverty and hunger, which naturally connect to health and well-being and reduced inequalities, all of which lead to economic growth.

“To get to zero hunger by 2030, we need also to work on many of the other SDGs, and we have to recognize many of the trade-offs that must occur,” Elouafi said. “In terms of producing more, are we harming biodiversity? Is there a way to produce more in certain ecosystems, but keep other ecosystems for environmental services? There are many trade-offs that need to be well studied, well analyzed, and that countries need to consider as they are developing their national programs.”

Bringing tech to the table

While 2021 has provided many opportunities for stakeholders to come together to discuss and design new agri-food systems linked to mega-agendas like climate change and biodiversity, time is of the essence in addressing these problems.

“There are only nine years left until 2030 to fulfill our global development agenda and our promises, and there is really no time to lose,” Elouafi said. “We are losing very important time to reduce poverty, to increase nutrition, to do better for the environment. We need to have a better idea of what's coming onto the market so we can get ready for it, so once the technology is ready we can use it at its fullest capacity.”

FAO is creating a study to look at the technological breakthroughs that are expected to contribute to achieving agri-food system transformation over the next 10 to 30 years. The organization seeks to make policy makers aware of these disruptive technologies to better anticipate investment needs and guide future policies for emerging innovation.

Solving innovation inequity

Critical to implementation is adequate financing, capacity and governance.

“Governments, especially of rich and middle-income countries, need to review the level of their investment in food system science and allocate at least 1% of their food system-related GDPs to food-system science and innovation,” she said. “More attention must be paid to strengthening local research capacity and developing more inclusive, more transparent, and more equitable science partnerships promoting international research cooperation — and addressing intellectual property rights and issues where they hinder innovation that can serve food and nutrition security, food safety and sustainability goals.”

Technology and innovation also need to be brought to the areas where it is most desperately needed.

“Innovation is not the same cost for everybody … Those that need it the most often have to pay the most for it, but that doesn't make much sense. We need to make innovation more affordable at the smallholder level, to the poorest of the poor farmers,” Elouafi said. “The only way to do that is to make sure we develop the local private sector in those areas. That local private sector could be affiliated with a multinational company, but there has to be local manufacturing so that the goods produced are affordable to those who need them.”

An example of the inequity of support for international development is the proportion on money countries allocate for defense spending each year, but Elouafi is hopeful that increased public attention and interest in global problems will shift support to these critical needs.

“I don't think the issue is a financial issue, when you look at the numbers — particularly when you include the private sector — the numbers are huge. There are trillions and trillions of dollars available to address this,” Elouafi said. “Even very poor countries put so much money in defense. If they put a percentage of that into international development, into the agri-food system, we would not need much resource mobilization anymore. One percent of the armament budget currently spent worldwide would give us plenty of money. It's possible — if the will is there and if we come to an agreement that we are interconnected. We are in this boat together, and we need to save all of us so we do not all go into extinction.”