Chicken is one of the most widely eaten proteins in the world. The poultry industry contributes more than $41.8 billion to Georgia’s economy each year. The U.S. alone consumes 8 billion chickens per year and approximately 250 eggs per capita. With the help of modern breeding techniques, there has been a drastic increase in meat yield and egg production to help meet this high demand.

However, as chickens grow larger and produce more eggs, growth-related issues in broilers and laying hens have become more common. Researchers at the University of Georgia are finding ways to combat these issues, which can affect animal welfare and lead to production losses.

A recent journal article published in Poultry Science studied the effect of 20(S)-hydroxycholesterol, a naturally occurring bioactive compound, on satellite cell proliferation and differentiation of broilers and laying hens. Satellite cells are muscle-specific stem cells that are responsible for the post-hatch growth of skeletal muscles by increasing protein synthesis levels in muscle cells and resulting in muscle growth.

Led by Woo Kim and Yuguo Tompkins in the UGA College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, in collaboration with Sandra Velleman, professor at The Ohio State University, the study examined the use of the compound to potentially improve both bone health and muscle growth.

“One of my biggest research focuses is bone health. I am working with broilers and laying hens,” said Kim, an associate professor in the UGA Department of Poultry Science. “With broilers, we genetically select for muscle growth, so there are bone issues, like lameness. My research aims to help the bone health in broilers and laying hens.”

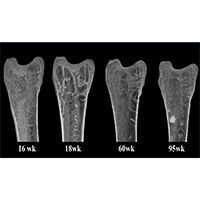

The study found that 20S has a positive effect on bone health in birds.

“One of the things about bone is that minerals and vitamins are very important. It is rare that we have other bioactive compounds to stimulate bone health and bone development. One of the compounds we found is 20S, an oxidized cholesterol that is naturally occurring. Certain compounds, like 20S, have potential bioactive properties. We found the 20S actually stimulates bone cell growth and also modulates muscle growth in some cases,” Kim said.

Although higher amounts of 20S did cause negative effects on muscle development in the birds, Kim and his team have identified treatment levels that can improve bone health without having a negative effect on muscle development.

“20S has the potential to balance out the bone and muscle growth or be a biomarker to help find the edge between bone and muscle growth in both broilers and laying hens. This could also be beneficial in solving some of the animal welfare concerns,” said Tompkins, a third-year doctoral candidate in Kim’s lab who is studying broiler bone health and who facilitated communication with Velleman’s lab in addition to performing lab research and writing.

The results of the study indicate that producers may be able to use this compound to prevent the loss of birds due to skeletal issues. This would mean more money for producers, more product for consumers and better bird health.

“We found that this 20S compound is actually stimulating bone cell growth and slowing muscle cell growth. It was the first time that anyone studied whether this specific compound regulated muscle cells. In the poultry industry, specifically the broiler industry, a big issue now is woody breast … white striping and also it looks like the muscle is abnormally formed,” said Kim, adding that the defect affects meat texture and quality. “I think that this new naturally occurring bioactive compound can minimize the occurrence of muscle abnormalities in broilers.”

Kim is looking at the research from an animal-welfare standpoint, as well as for production and meat quality.

“I want to become a problem solver. In the poultry industry, the main goal is production, but we also need to consider the environment and welfare. The bone-related issue is one of the important welfare issues. We want to promote meat production but minimize welfare issues in poultry. That is why I am interested in this bone-related research,” Kim said.

The study, which was funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture under the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative program, also highlights the importance of collaborative research. For example, Franklin West, associate professor in the Department of Animal and Dairy Science, assisted Kim’s team with the in vitro stage of the study, resulting in another publication in Frontiers in Physiology. Since West specializes in stem cell work, his expertise guided the team in reaching their research goals. Roshan Adhikari, who earned his doctoral degree in poultry science in 2017, and Shengchen Su, a former postdoctoral scholar in Kim’s lab, also successfully established a novel mesenchymal stem-cell model derived from chicken compact bones and a bioactive compound delivery system to chicken embryos via in ovo injection during the 20S research.

“Our team has great diversity in regards to academic and cultural backgrounds. It’s amazing working closely with them,” Tompkins said.

For more information on the UGA Department of Poultry Science, visit poultry.uga.edu. To learn more about CAES research, visit caes.uga.edu/research.