A literature review by University of Georgia researchers has helped identify the most effective antimicrobial agents for preventing the spread of COVID-19 within the food supply chain.

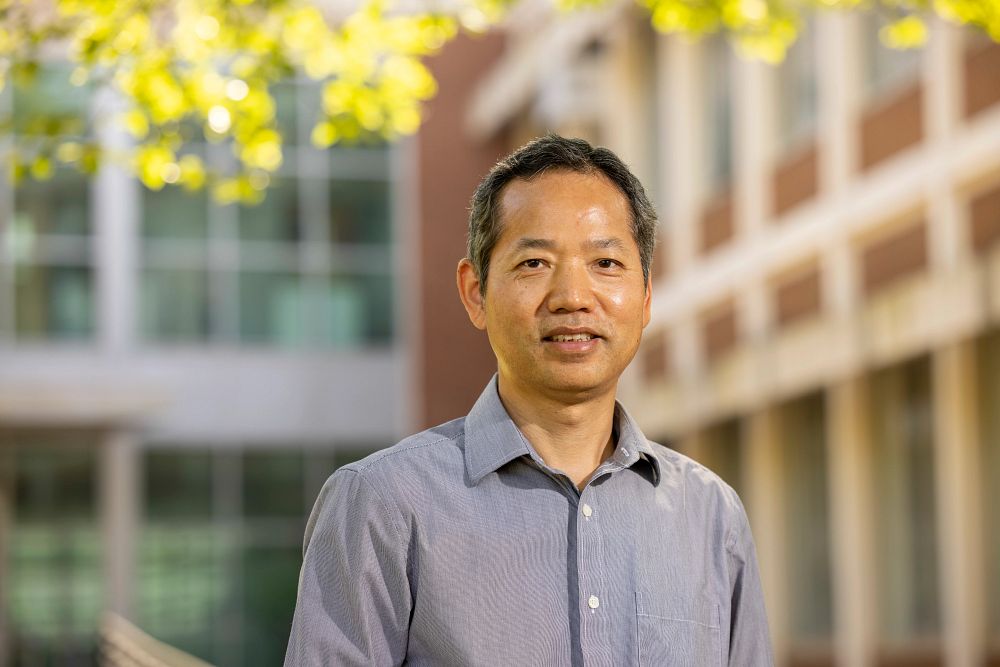

As COVID-19 began to spread throughout the U.S. earlier this year, Govind Kumar, an assistant professor in the Department of Food Science and Technology and a faculty member in the UGA Center for Food Safety, Laurel Dunn and Abhinav Mishra, assistant professors in the Department of Food Science and Technology, and Center for Food Safety Director Francisco Diez collaborated to determine ways they could contribute to the knowledge base for members of the food industry regarding the novel coronavirus.

“Meat manufacturing plants began to shut down because so many people in these industries were getting sick. We are not virologists, but this is a medical problem that definitely affected the food chain,” Kumar said.

With information and scientific studies about the virus being released at a rapid rate, the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences researchers decided to examine relevant studies to identify and share practicable information for use in the food industry. The research team looked at studies on a range of biocides effective in eliminating or reducing the presence of coronaviruses from surfaces that are likely to carry infection, such as clothes, utensils and furniture, as well as skin, mucous membranes, air and food contact materials.

After reviewing and synthesizing the information from more than 100 sources, the online journal Frontiers in Microbiology published the researchers’ findings in “Biocides and Novel Antimicrobial Agents for the Mitigation of Coronaviruses” in late June.

“We wanted to go through the whole food supply chain — from processing to packaging to retail — to look at interventions to limit the spread of coronaviruses. This is not limited to handwashing, but looks at everything — how you can remove it from the air, from food contact surfaces. We asked a lot of tough questions and we feel we have answered those in this paper,” Kumar said.

Since it was published, the paper has received interest from all over the world. According to the journal, the article has more views than 67% of all Frontiers articles on the website at frontiersin.org.

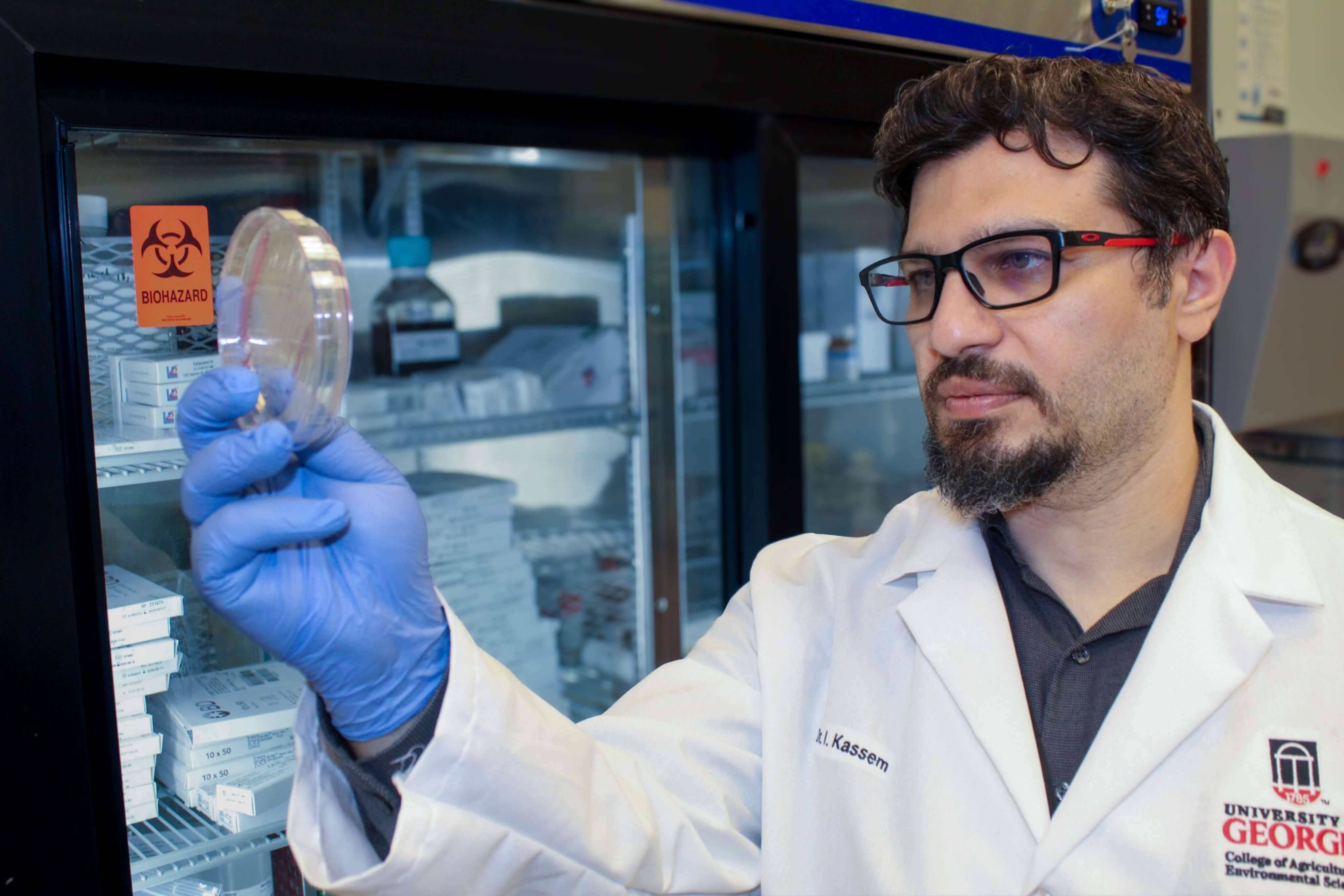

“One of the main research areas we work on is the development of novel sanitizers and I do a lot of outreach on their proper use,” said Dunn. “For me, it has been industry — mostly in Georgia, but others from around the world — who stumbled on this and had questions.”

The research team specifically focused on the effects of alcohols, povidone iodine, quaternary ammonium compounds, hydrogen peroxide, sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl), peroxyacetic acid (PAA), chlorine dioxide, ozone, ultraviolet light, metals and plant-based antimicrobials. The review highlights the differences in the resistance or susceptibility of different strains of coronaviruses, or similar viruses, to these antimicrobial agents. The team also worked with microbiologists Charles Gerba and Kelly Bright from the University of Arizona who are currently performing research on detecting the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater.

While the review reinforced the effectiveness of certain antimicrobials — such as bleach and alcohol — on surfaces, it also addressed studies on agents that can be used to protect workers themselves.

“A lot of what I’ve gotten have been questions about what can be used on the skin. We got crazy questions like, ‘Can we spray our workers with chemicals?’ A lot of questions have been about what steps they can take in certain types of facilities. It is not necessarily about sanitizer selection, but what to do in general,” said Dunn, who does outreach and extension work in on-farm and packinghouse microbial safety.

While handwashing and the use of sanitizers are commonly implemented practices in food production plants, to address the spread of COVID-19 from asymptomatic workers, who often work in crowded conditions, the team focused on a number of studies of two substances — povidone iodine and iota carrageenan — that were of particular interest in preventing person-to-person transmission of coronaviruses.

“Povidone iodine is very effective against coronaviruses and, in Europe and Asia, people use povidone iodine for oral rinses and nasal sprays. Because this is an airborne virus, the first place it goes is into the nose and it attaches to the cell receptors in the nose,” Kumar said.

A seaweed-based antimicrobial polymer, iota carrageenan is commonly used as a food thickener and, in a 2018 study, demonstrated the ability to inhibit coronaviruses and other respiratory viruses.

“When sprayed in the nose in nasal spray form, iota carrageenan can form a protective film over the nasal membranes and keep the virus from attaching,” Kumar said.

While not performing any direct research, Kumar and Dunn said the synthesis of information from a variety of studies — some from this year and others done over the past 20 years — can serve as a sort of “CliffsNotes” for industry members seeking the most relevant and useful information on preventing transmission of COVID-19.

“We were very excited about that and we want to get that information out for industry to investigate further or do more research,” Kumar said.

The group shared their findings with Atlanta-area anesthesiologist Constantine Kokenes, with whom they connected when donating personal protective equipment from their labs to local frontline healthcare workers, an effort spearheaded by Dunn.

Through conversations with Kumar, Kokenes obtained and studied papers about the potential benefits of povidone iodine rinses and iota carrageenan nasal spray. Using specific formulations, he purchased the materials and mixed his own preparations to use when treating and intubating COVID-19 patients in the intensive care unit at Emory Decatur Hospital.

“Before elective surgeries were cancelled — from early March through mid-April — I did this for six weeks,” said Kokenes, who also followed recommendations to protect himself, including using masks and face shields and shaving his beard of 30 years to ensure a proper seal on his face mask.

“I did this for my own good. It is only logical and rational to explore all options and protect yourself,” he said. “There is a lot of groundwork that has been done since the early to mid-2000s after the first SARS and MERS virus outbreaks. Dr. Kumar and his team have been on top of that.”

The team’s full paper is available at www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01351/full#F2. More information on the Center for Food Safety is available at cfs.caes.uga.edu.