Asking a busy woman to report her daily activities can give researchers insight into how she spends her limited time and whether child-care and other household responsibilities leave her with enough bandwidth to adapt to changes and accept new technologies.

Traditional time diaries have limitations, though, particularly in places where women often aren’t literate and don’t follow time on a clock.

A project spearheaded by a team from the University of California-Santa Barbara (UCSB) through the Peanut Innovation Lab plans to use voice recordings and biometric devices to capture a more vivid picture of the demands on a woman’s time and energy.

Researchers are studying the roles and responsibilities of women in Senegal, where peanut is an important supplementary crop for households and often handled by women. Researchers want to know how the peanut value chain is impacted by the number of children a woman has, the power dynamics in her household (which may contain multiple wives) and climate shocks she faces.

Are women who have more children busier, so they participate less in peanut production? Are women who manage the household busier and less able to adopt best management practices for peanut production? Are time-poor women less able to adapt to climate shocks?

The team conducted an ethnographic assessment in Senegal in February (just before global pandemic shut down most research operations), even as grad students back in southern California began to validate the biometrics system.

In the Wrist-worn Heart and Activity Monitoring (WHAM) study, participants wear watches and wrist-worn voice recorders continuously for two weeks. While the heart monitor takes a reading every 10 minutes, a timer on the voice recorder asks three times a day for participants to report on their activities – where they are and what they are doing, as well as what they have been up to since the last report.

The heart rate data gives some insight into how much energy the person is exerting, but also shows how much rest she is getting.

Five UC-Santa Barbara students in two households participated in data collection earlier this year, creating nearly two hours of extemporaneous voice recordings, as well as heart-rate data and a traditional written time diary for the team to analyze.

Time tracking was put on hiatus during shut-down for COVID-19 (not just because the data would be skewed, but because like most researchers, the UCSB team was barred from human subjects research).

Now that restrictions are accommodating at-distance data collection, two more groups of participants are lined up to collect their personal data – a group of grad students this summer and a group of faculty this fall.

“We really want to look at two things. With sleep, we want to see if sleep on the heart-rate monitors corroborates what we see in the written diary and recording,” said Sophia Arabadjis, a graduate student working on the project. Defining sleep may involve setting parameters for what the average person’s sleep looks like in the heart-rate data.

“Then, we want to look at exertion, which is more complicated because of the 10-minute interval,” Arabadjis said. “We can see that the heart rate was elevated at a reading during a time when the person reported doing a certain activity, but we don’t know about the few minutes before or after that reading.”

Over the coming months, the team will continue to analyze the ethnographic assessment data collected in Senegal, while evaluating the WHAM pilot data from California, aiming to validate written versus recorded time use. By next spring, they hope to validate written versus recorded time use, and solve one technology challenge they encountered in early work in Senegal.

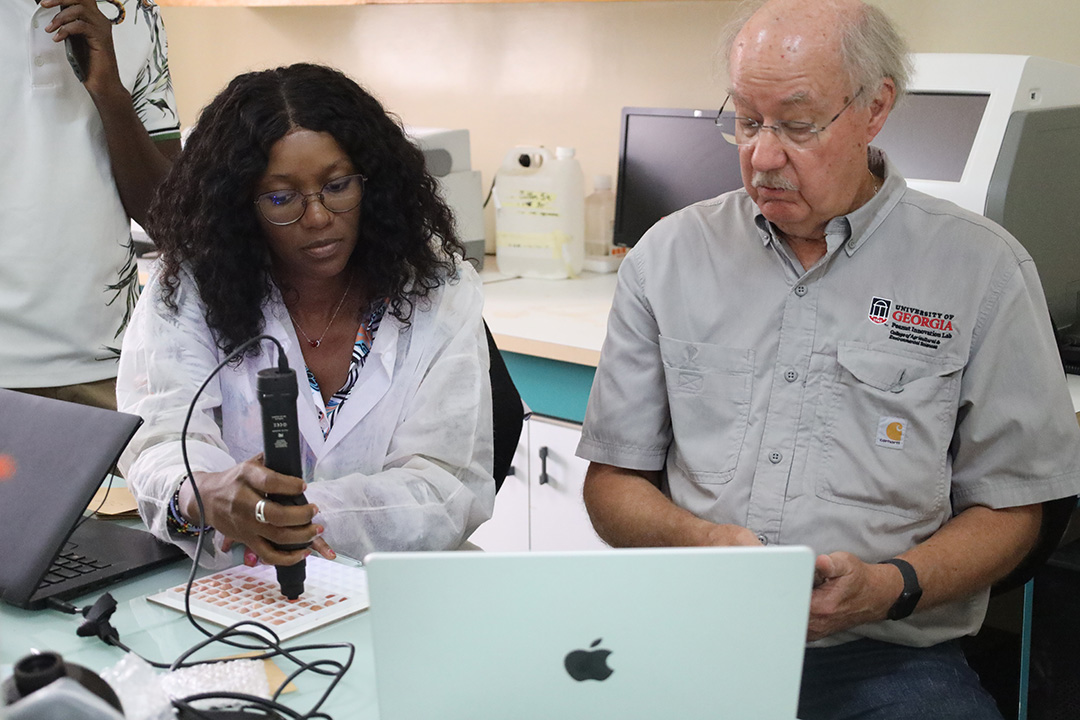

All wrist-worn heart monitors use photoplethysmography (PPG) technology, which uses a light source and a photodetector on skin to measure the volume blood circulating. The sensors work better with light skin, so the team working with test data to see how much information the technology can collect if a person has very dark skin and whether a different type of heart-rate monitor is better. An alternative would be a traditional EKG chest strap that monitors electrical activity of the hear itself as opposed to blood volumes. However, it isn’t as comfortable to wear and has a shorter battery life, making it a poor tool for implementing in Senegal.

The project is led by Stuart Sweeney and Kathy Baylis, in Department of Geography at UC Santa Barbara, along with Samba Mbaye of the Centre de Recherche pour le Développement Economique et Social, and Mamadou Ba of the University of Thies in Senegal.