Women make up half of the agricultural workforce in sub-Saharan Africa, yet researchers don’t always consider how the details of women’s lives might have a huge impact on the outcome of the research or whether resulting technology succeeds or fails on the farm.

With Gender and Youth as both a key focus area and a cross-cutting theme of all projects for the program, the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Peanut is looking to inspire and empower scientists to explore how men and women live and farm differently and how those differences can impact the objective data that comes from research.

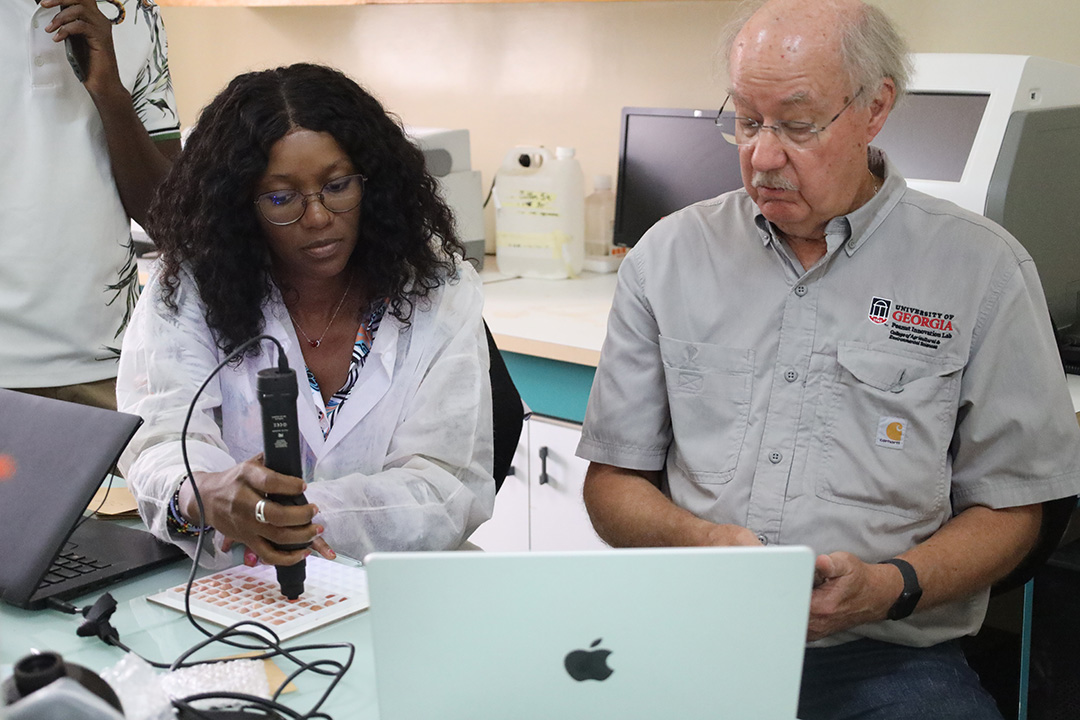

In a morning workshop led by Helga Recke, co-founder of African Women in Agricultural Research and Development (AWARD) and Jessica Marter-Kenyon, a post-doctoral researcher who advises the lab on gender, the lab invited students and scientists from any discipline to explore the topic. “Gender Responsive Agricultural Development and Communication” was held on the University of Georgia campus on Dec. 17.

The connection to gender may not seem as obvious to a bio-physical scientist, such as an entomologist. What difference does the gender of the farmer make to the pests and diseases?

But men and women throughout the world have very different time constraints, household responsibilities and ways of gathering information. A woman might interact with different plants and insects she finds while collecting water, for example, be less inclined to apply low-cost inputs because of time- and cash-constraints, or miss out on the latest cooperative extension information if it’s broadcast on the radio.

The workshop brought together UGA grad students and faculty in crop and soil science, agricultural economics, ecology, poultry science and other disciplines from UGA, as well as visiting scientists who work on the Peanut Innovation Lab’s five gender and youth projects. Those scientists, who are exploring market incentives for high-quality groundnuts in Ghana, time poverty and other constraints of women farmers in Ghana and Senegal, and the factors that limit youth in Uganda and Senegal from going into agriculture, met in Athens the day before to discuss the progress of their projects.

Male farmers in sub-Saharan Africa see yields that are 20-30% higher than female farmers achieve. The cause is multi-faceted – from land control, to credit for inputs, to access to information. Women might even choose a lower-yielding or less profitable variety if it’s easier to prepare or children in the household prefer it. Since studies show that women’s earnings are more likely to be reinvested in household expenses and child education, the yield gap is important.

While much of the workshop revolved around research in Africa, the group also explored examples in the U.S. context where women are often considered the “farmer’s wife,” though they participate in similar tasks on the farm as men and where the majority of new farmers in the aging farming population are actually women.

A growing acknowledgement of the roles that women play in agriculture and related sciences will be critical in addressing future food needs across the globe.