Shrubs that grow wild in West Africa could be key in boosting yield and giving farmers assurance that they can make a profitable crop, even in the drought prone, food insecure Sahel region. Through the Feed the Future Peanut Innovation Lab, researchers are exploring how best to use two shrubs species in cultivated peanut fields in Senegal to improve the soil health, tap into moisture far below ground and lower soil temperatures.

Peanut is an important crop in Senegal, where 27% of households grow some peanuts and more than half of the poorest families cultivate a crop, often a rotation of millet and peanut. Still, conditions are challenging, with sandy, overworked soil and extremely dry climate.

A team of U.S., Senegalese, and French researchers developed the Optimized Shrub System (OSS) over 20 years, utilizing the native shrubs Guiera senegalensis and Piliostigma reticulatum. These plants create a natural irrigation system, sucking water from deep below the surface to irrigate neighboring crops, and at the same time, increase organic matter in farmers’ fields. The ubiquitous shrubs are found across Senegal, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Chad, areas that receive less than 500 mm (or 20 inches) of rain a year.

Richard Dick, a professor at The Ohio State University, first noticed these plants two decades ago while travelling through rural Senegal. A soil scientist, he saw that the shrubs thrived despite the arid conditions and marveled at the biomass they created. Then, he wondered, could these shrubs help the surrounding plants?

“This is a local resource that has largely been overlooked as a means to addressing crop production in the Sahel,” he said.

Dick and long-time collaborator Ibrahima Diedhiou at the University of Thies have been investigating the plants’ role improving crop yields and remediating degraded soils. Out of this research largely funded by the US National Science Foundation came the Optimized Shrub-intercropping System (OSS).

The shrubs grow in fields naturally, but the OSS increases their density from 200-300 per hectare to 1,500 per hectare, and calls on the farmers to incorporate the shredded stems and leaves into the soil rather than the current practice of burning of the shrub residue.

Their research shows how the shrubs “bio-irrigate” adjacent crops. Using deep roots, they draw water from wet subsoil and release it to dry surface soil at night when photosynthesis stops. Experiments have shown that this lifted water is taken up by adjacent millet crops.

The OSS also returns biomass to the soil, increases soil quality and sequesters carbon, an important benefit for combatting global climate change.

“With sandy, arid soil, you need to add biomass. In the absence of organic inputs to these soils, even when fertilizer is added, yields continue to go down. The shrubs provide a continuous source of biomass for soils,” Dick said

The shrub system also keeps soil temperature lower, even when the shrub has been coppiced, or cut off at the ground. High soil temperature can inhibit germination, and is a special concern for peanuts which are susceptible to toxin-producing molds that flourish in hot, dry soil.

The difference is obvious to see in fields where Dick and colleagues have researched the symbiotic relationship between the indigenous shrubs and cultivated crops.

“You show this to farmers and they are amazed,” Dick said of successful test plots. “Farmers are familiar with the shrubs but do not know how to grow shrub seedlings. We have developed a simple method for growing seedlings, that farmers readily adopt.”

Peanuts grown in the shrubbing system have 10% to 20% higher yield, but also more peanut haulm (vines and leaves), which are a source of income as animal fodder. (Yield increases are even more dramatic for millet.)

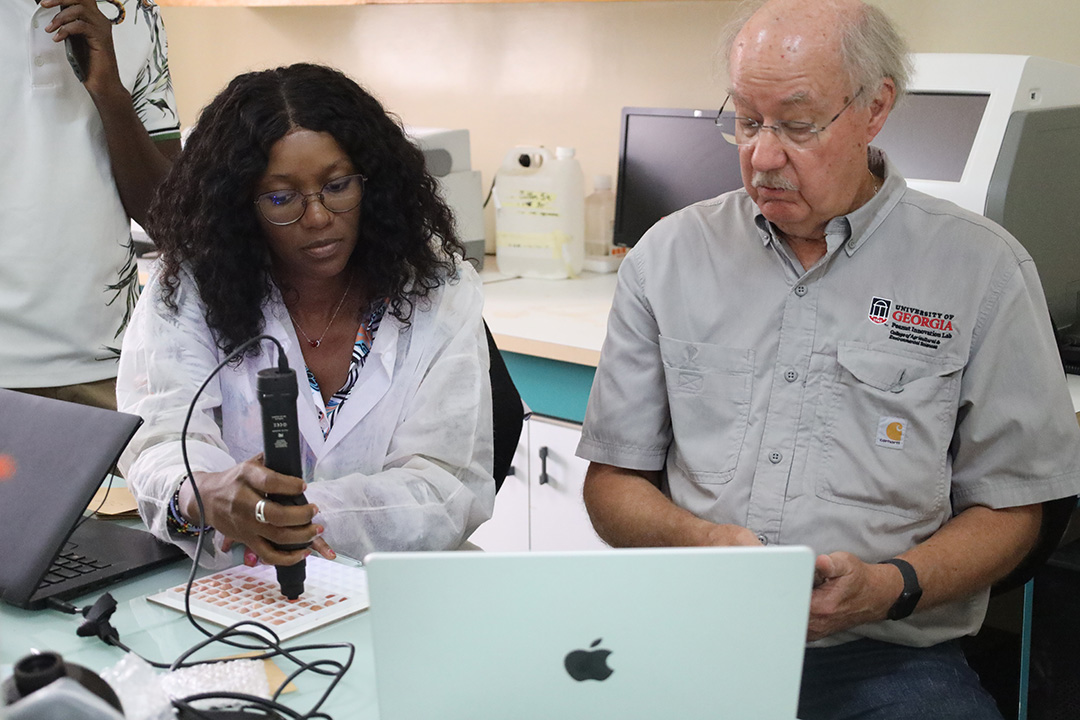

Now, with support from the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Peanut, Dick is working with Diedhiou and Idrissa Wade, both of the University of Thies in Senegal, Issa Faye and Alfred Tine of Institut Sénégalais de Recherches Agricoles (the national agriculture agency in Senegal) and Amanda Davey, also from Ohio State, to test the shrubbing system in Senegalese farmers’ peanut fields.

Research has demonstrated the benefits the shrubs can offer to crops, but changing the way farmers manage their resources and time requires more study.

Thirty farmers have been enlisted to adapt the OSS for a field on their farm, while an adjacent field is worked under the traditional system, where there are fewer shrubs and farmers burn the residue. A cadre of technicians and graduate students will monitor economic and agronomic performance, and soil parameters for these two systems for the participating farmers.

By interviewing farmers through surveys and focus groups, the team is exploring the cultural, gender and labor constraints that may be stumbling blocks for farmers to adopt the system. For example, shredding the shrubs and returning the residue to the soil, rather than the current practice of burning, takes additional time and effort that farmers might not be willing to invest.

To address the possible labor constraint of OSS, the project is investigating the potential of simple mechanized equipment to shred the plants.

Finally, an outreach campaign will broadly disseminate the results to farmers, national research and extension agencies, and policymakers.

When the results are obvious, farmers are eager to try the system.

“Even if this is not implemented across all cropped fields, it could be implemented on a portion of the farm as an insurance plan to maintain crop production even in drought years” Dick said.