It may seem like everyone on Earth has an equal chance of being born male or female. It’s about a 50-50 split, after all.

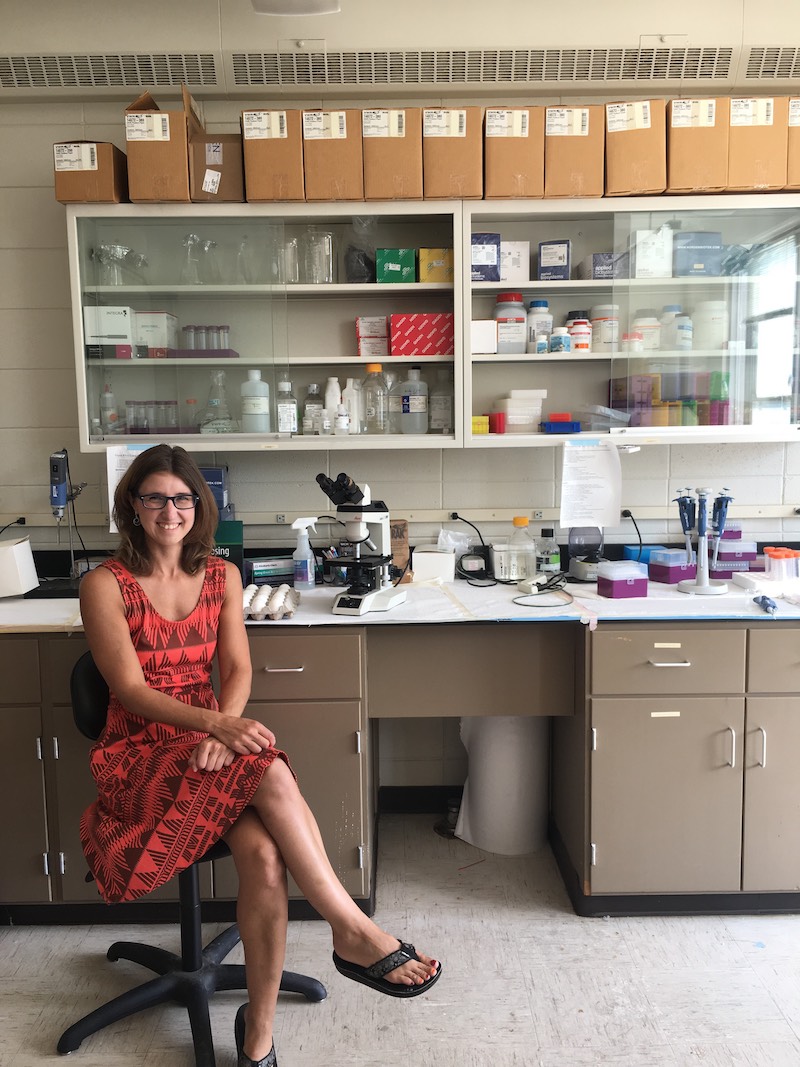

But University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences Associate Professor Kristen Navara has found that it’s not that simple.

Stress and a lack of resources can trigger hormonal shifts that make it more likely for a mother to produce female offspring.

Navara has found that it's true for birds, and although the mechanism is different, it’s true for humans and most mammals.

Women who gain less weight during pregnancy are more likely to have female offspring, and wild birds that experience food shortages or other environmental stress produce more female chicks.

“So all birds and mammals produce these hormones, and that’s what elicits physiological responses that help them survive environmental challenges,” Navara said.

“When we knew that wild birds were able to adjust the sex of their offspring, our first question was, ‘What is responsible for transducing those environmental conditions into physiological signals that could control sex ratios?’ The answer was stress hormones,” she said. “We believed those stress hormones might mediate this effect on sex ratio, and we have found that they are, at least in part, a player in the process of manipulating sex ratios.”

They found that treating laying hens with corticosterone, the stress hormone, can influence the sex chromosome the hens’ offspring inherit.

In early 2018, Navara published a book exploring the factors that skew sex ratios in animals, “Choosing Sexes: Mechanisms and Adaptive Patterns of Sex Allocation in Vertebrates.” It is one of the only works that takes a comparative approach to explain the powerful use of hormones to manipulate sex ratios across species.

Understanding how stress hormones affect the sex of the hens’ chicks is invaluable information for the poultry industry, which needs male chickens to populate broiler houses and female chickens to populate laying houses.

“We know that birds in the wild have the ability to alter the sex of their offspring without our help,” Navara said. “We want to harness that ability for the industry …

In the poultry industry, the sex of the chicks is particularly important. So we’re trying to find a treatment that would program the hen to produce more of the desired sex.”

Currently, with the help of the Georgia Genomics and Bioinformatics Core at UGA, Navara’s team has identified a handful of genes that could potentially be the links through which stress and stress hormones control the sex of progeny. They are now in the process of verifying whether expression of these genes does, in fact, change when stress triggers sex-ratio skews.

Up until this point, they’ve only been able to affect the sex ratio of the hen’s chicks by treating her with hormones, a practice that is banned in the poultry industry.

Their next step is finding a hormone-free treatment to trigger the gene responsible for translating stress into hormones to skew the sex ratio of chicks. Eventually, this could be accomplished through breeding, but that is a project for the future, Navara said.