Georgia wines may not have the same cachet as California chardonnays or French Burgundies, but they’re earning new accolades each year thanks to a community of dedicated grape growers and a little help from University of Georgia Cooperative Extension.

UGA Extension agent Paula Burke in Carroll County, Georgia, is working with the Vineyard and Winery Association of West Georgia, Georgia wine growers and the UGA Agricultural and Environmental Services Laboratories (AESL) to help produce better wines by perfecting growing methods.

According to the UGA Center for Agribusiness and Economic Development, Georgia’s fledgling wine industry has an impact of $81.6 million on Georgia’s economy each year.

There’s been very little research into what it takes to grow wine grapes in Georgia. Most of the grape research in the state has focused on muscadine varieties, but wine growers in west Georgia are using hybrid vines that incorporate the genetics of classic viniferous or European varieties and the genetics of wild grapes to help combat disease.

“These hybrid grapes grow very vigorously,” Burke said. “They seem to love poor soil, and they just seem to love this area of Georgia. The poorer the soil, it seems the faster they grow.”

These are Texas-cultivated hybrids, like Blanc du Bois, Norton, Lenoir and Villard Blanc. They can be treated like classic pinots and merlots in the wine barrel, but are resistant to problems like Pierce’s disease, which makes wine grape cultivation very difficult in Georgia.

“When you say ‘Norton’ or ‘Blanc du Bois,’ nobody knows those varieties, but they make fantastic wines,” Burke said. “You can make sweet wines out of them; you can make dry wines out of them … They’re great wines, they’re just not the merlots or pinots that you see in the store.”

But even if the right variety of the right crop is planted in the right place, knowing the right growing methods for the region can greatly impact growers’ success, Burke said.

Burke started working with nearby Haralson County, Georgia, winery Trillium Vineyard in 2014. She took copious soil samples to help the AESL, which is best known for analyzing soil and water samples, develop soil-testing recommendations for hybrid grape wineries in Georgia. Burke also started working with owners Bruce and Karen Cross on variety testing.

The goal was to compare varieties of grapes and trellising systems to see which combination provided the best yields and the highest quality grapes.

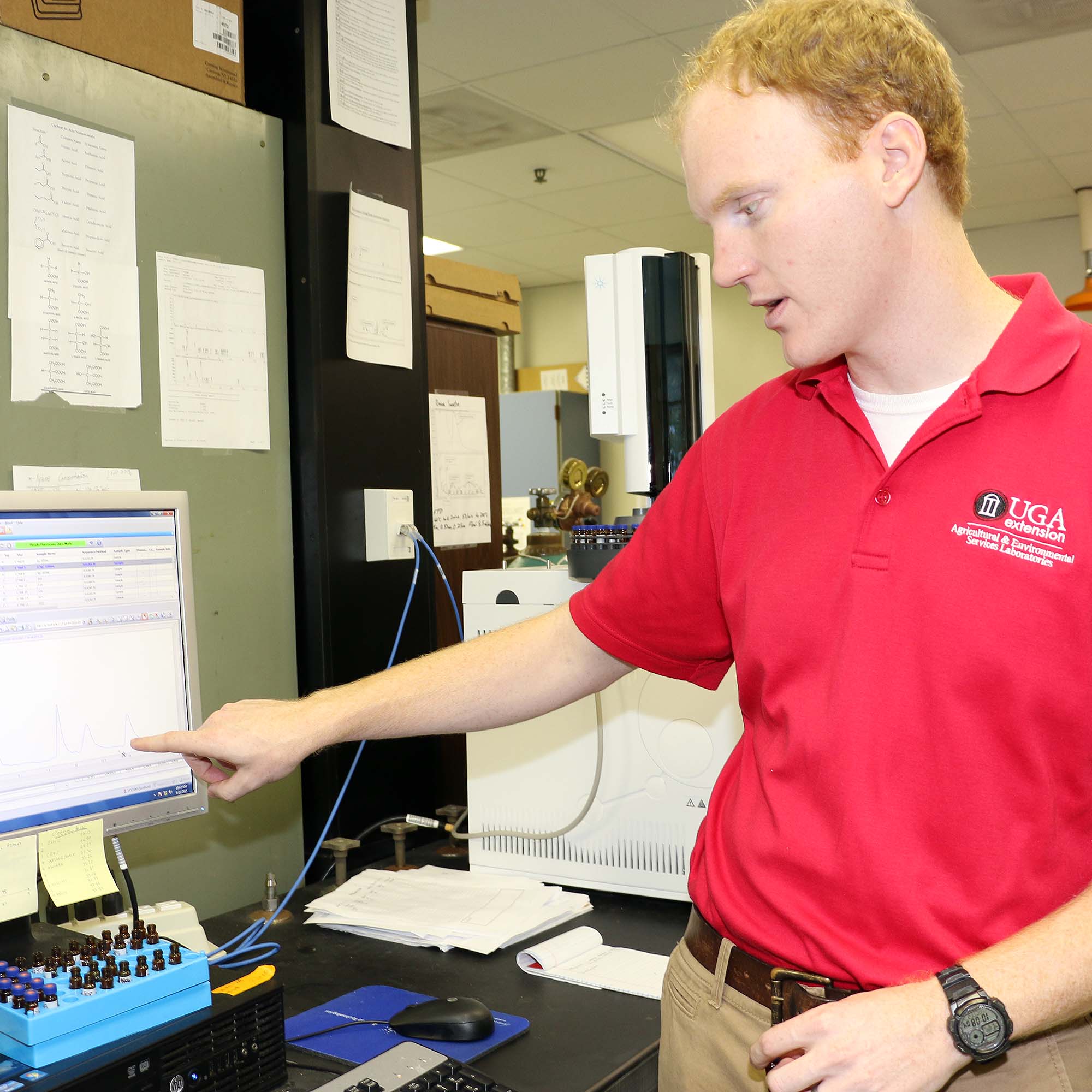

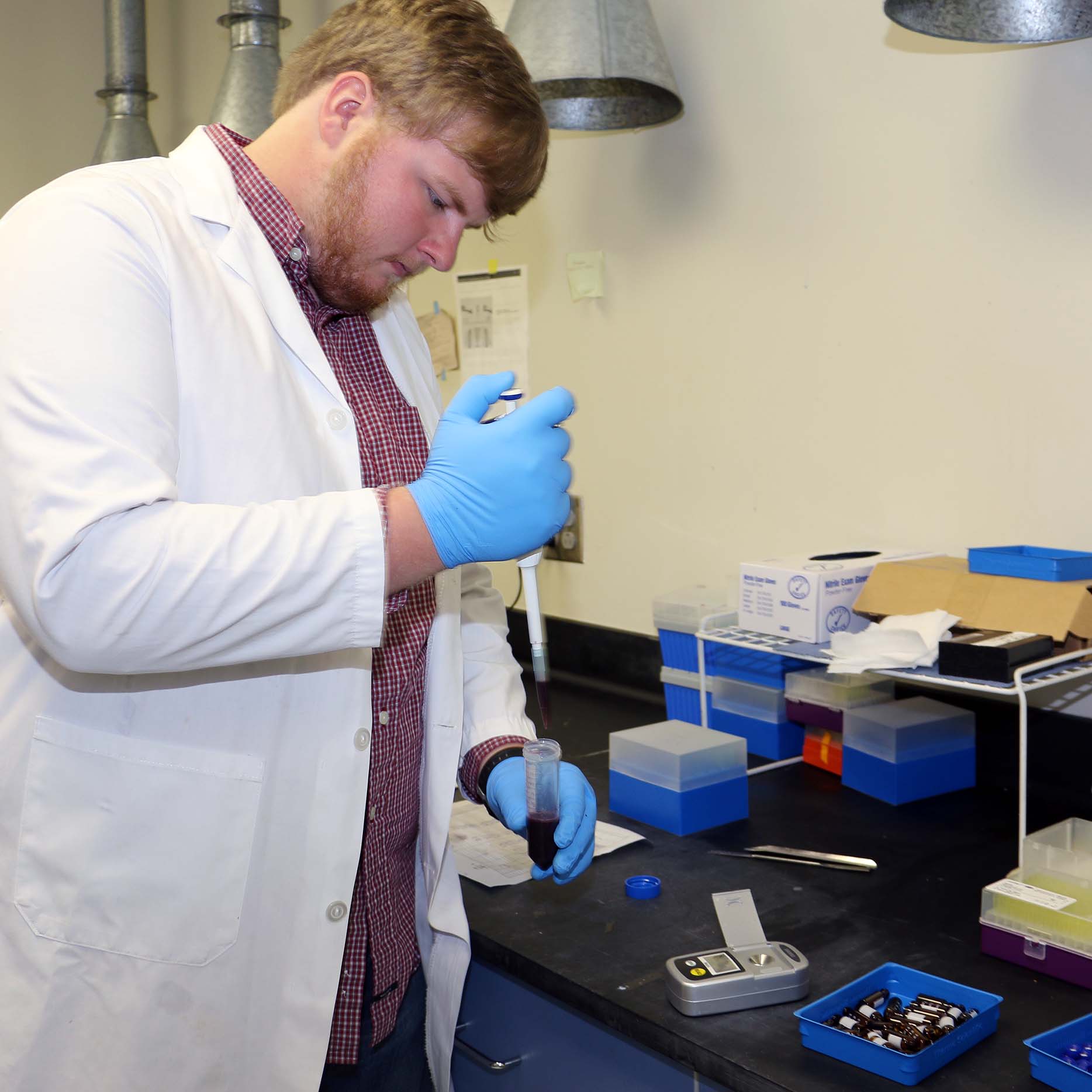

But determining the “highest quality grapes” can be subjective, and that’s where the team at the UGA Crop and Environmental Quality Laboratory, one of the labs that make up the AESL, had some influence. Daniel Jackson, manager of the lab, has taken on the task of quantifying what makes a grape great for winemaking.

Building on a testing system he developed to chemically describe the sweetness of Vidalia onions, Jackson developed a battery of tests for the Trillium Vineyard grapes.

Jackson and his team measure pH and titratable acidity (measurements of the acidity of the grape juice), how quickly that acidity will mellow and meld with other flavors, and the Brix and sugar profiles, which characterize the potential alcohol content of the wine and the overall sweetness of the juice.

For thousands of years, winemakers have developed a knowledge base about how growing practices affect the wine made from traditional wine grapes. Tests from the UGA lab allow Georgia’s wine growers to accelerate this process by using modern chemistry.

They’ll be able to skip the generations of trial and error and pinpoint the best uses for each variety of grape and how growing methods will improve the quality of each variety.

“This is a systematic approach to identifying how these varieties (which have not seen widespread use in this region) will perform in the vineyard and in the wine barrel,” Jackson said. “It’s allowing us to look at these newly adopted varieties and see how they respond to different growing conditions, how growing conditions affect quality and what kind of wines they can be used for.”

This information can help growers make informed decisions about which grapes to grow and which cultivation techniques will maximize yield and quality.

Burke and Jackson’s work with the Trillium Vineyard is being funded by a three-year grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and has received significant technical advice from Fritz Westover of Westover Vineyard Advising and Rachel Itle, a postdoctoral horticulture researcher on the UGA campus in Griffin, Georgia.

Separately, Jackson’s lab has started accepting grapes and wines from other Georgia producers.

More information about the UGA Extension AESL can be found at aesl.ces.uga.edu.