Terms like “gluten-free,” “natural,” “organic” and “locally grown” are popping up all over the grocery store and in the food media. It may seem like Americans are eating healthier than ever before.

In reality, only a select group of consumers are buying products that are marketed as being healthier or more environmentally conscious. Most consumers are still eating high-calorie, processed foods and make food choices based on taste and convenience rather than health claims.

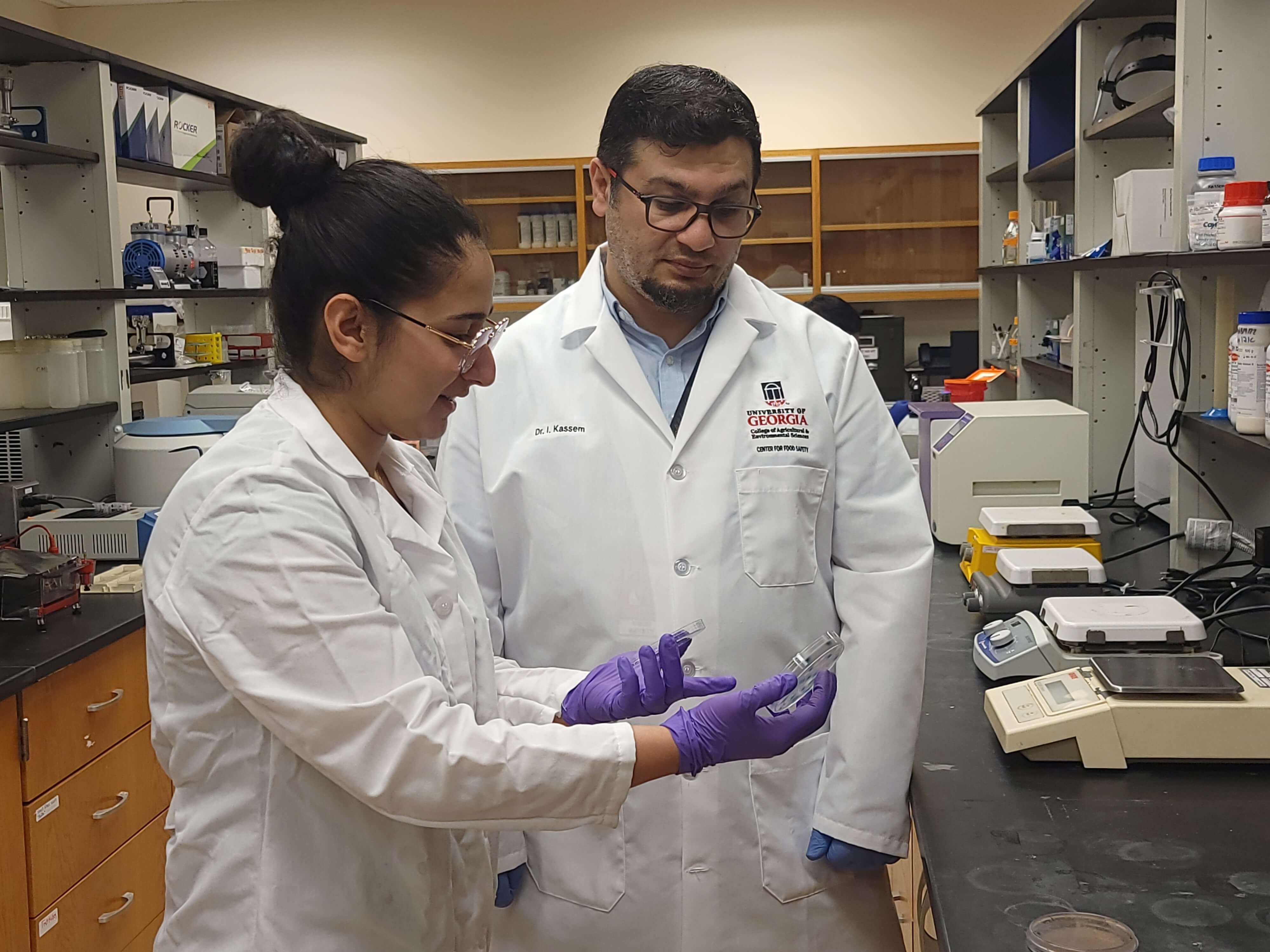

Food science professor Louise Wicker, of the University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences (CAES), studies what drives consumer choices and how to get people to eat healthier food.

She’s found that consumers who place a premium on foods that make these claims only represent a small segment of the population. Many more Americans build their diets around foods that are high in fat, salt and calories, and more than one-third of American adults are obese.

“How did we get to this place of obesity, under-nutrition and lack of awareness of sustainable agricultural practices by a large segment of the population?” Wicker asked at a recent Sustainable Food Systems Initiative seminar, a forum for faculty from colleges across UGA to share their research and to have meaningful dialogue on the issue of food production and consumption.

Until World War II, America’s under-nutrition problems were fueled by food insecurity. The priority was providing the public with adequate nutrients. After WWII, a number of changes in U.S. society, including women joining the workforce, led to a boom in the development of processed foods. Americans began over-consuming and making other lifestyle choices that resulted in taking in more calories than they burned.

In the last 50 or 60 years, average Americans have lost interest in cooking and lost cooking skills. In 1960, the average home-cooked meal contained 20 ingredients. Today the average home-cooked meal includes fewer than six ingredients. It’s not just that people have lost the desire to cook; many families have busy schedules that put cooking on the back burner.

When choosing between cooking dinner or going to their child’s school concert, for example, most parents prioritize spending free time with their children, which means buying pre-packaged meals and eating away from home, Wicker said.

One key to developing healthier eating habits is to “start with schools, so kids bring the habits home to mom and dad.” Children are likely to eat healthier if fruits and vegetables taste better and if their flavor profiles are shifted.

Moreover, there is evidence that obese and non-obese people experience food differently, Wicker said. “Obese individuals tend to prefer more salt, fat and sugar and are not satiated by the same amount as normal weight individuals,” she said.

Cutting the amount of sugar, salt and fat that children expect in their meals can short circuit this cycle early. Offering more and better fruits, vegetables and healthy options can eventually change students’ taste buds. Farm-to-school programs get kids excited about growing and eating vegetables.

Healthier eating for adults isn’t easy. Their feelings about food and taste preferences can take longer to change.

While people say they want healthier or more natural groceries, good intentions don’t always translate into sales or consumption of healthy choice foods.

Sometimes, health claims can actually turn consumers away.

For example, in spring of 2013, Burger King introduced Satisfries—French fries that were advertised as having 40 percent less fat than the McDonald’s fries. Sales were unexpectedly low, and by fall 2014, Burger King announced they would no longer offer Satisfries.

People have a misconception that food labeled as healthy tastes bad. Many food giants are starting to lower salt, sugar and fat content without telling consumers, Wicker said. The hope is that these “stealth health” initiatives don’t turn consumers away.

The Sustainable Food Systems Initiative is a collaborative effort between CAES and the Franklin College of Arts and Sciences, Odum School of Ecology, College of Environment and Design, College of Family and Consumer Sciences and Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources at UGA. The goal is to provide an interdisciplinary setting for students, professors and other scientists to address issues plaguing modern food production, like conservation of natural resources, feeding the growing population, environmental degradation and nutrition.