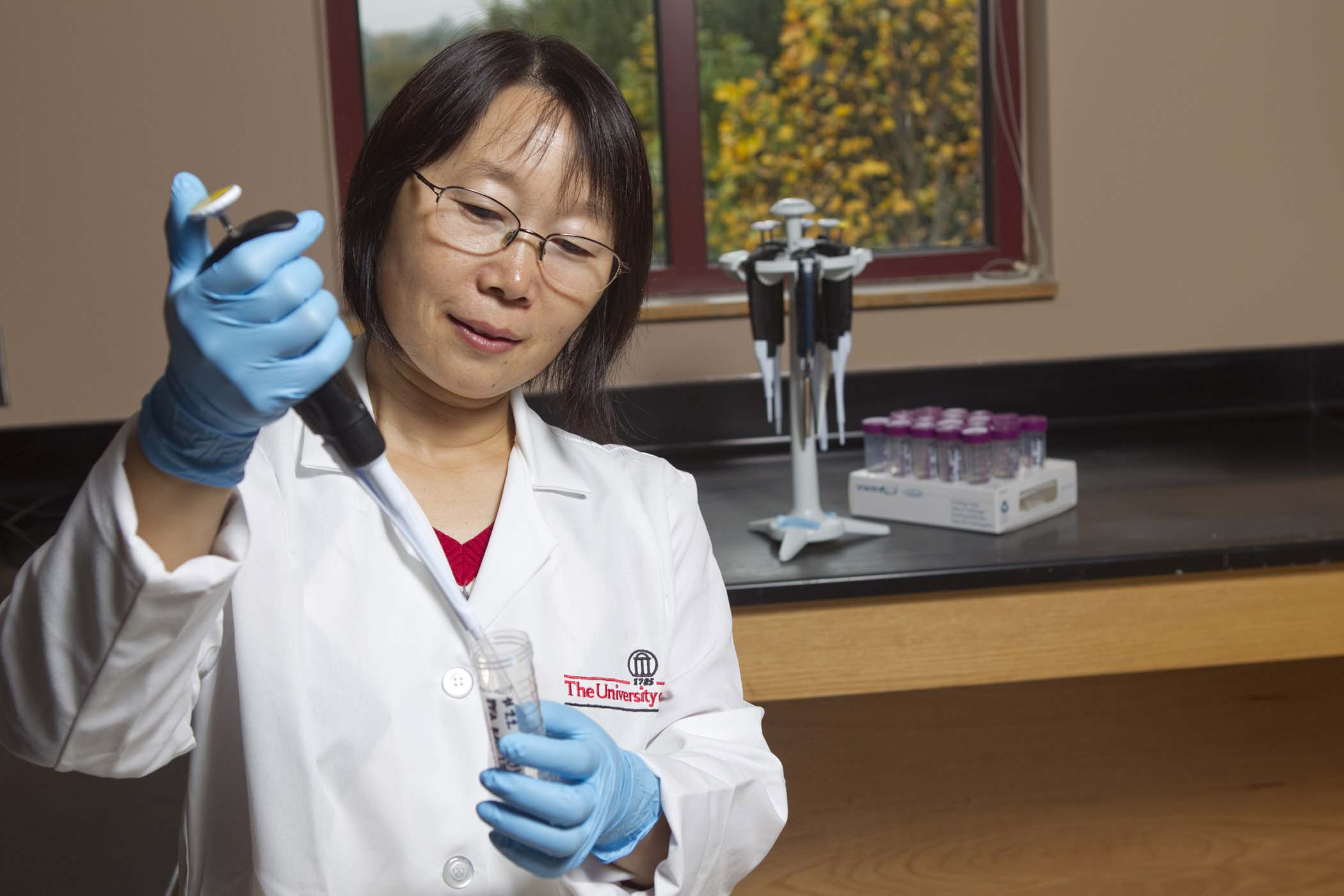

Most people don't give much thought to their 10,000 taste buds when they choose a chocolate chip cookie over an apple. University of College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences researcher Hongxiang Liu thinks about these tiny sensory organs nearly every day.

Liu, an assistant professor in the UGA Department of Animal and Dairy Science, has studied taste organs — the taste buds and taste papillae on which they reside — for more than 12 years to better understand the sense of taste and how it develops. She also plans to study the relationship between taste organs and obesity as a member of both the UGA Regenerative Medicine program and UGA Obesity Initiative.

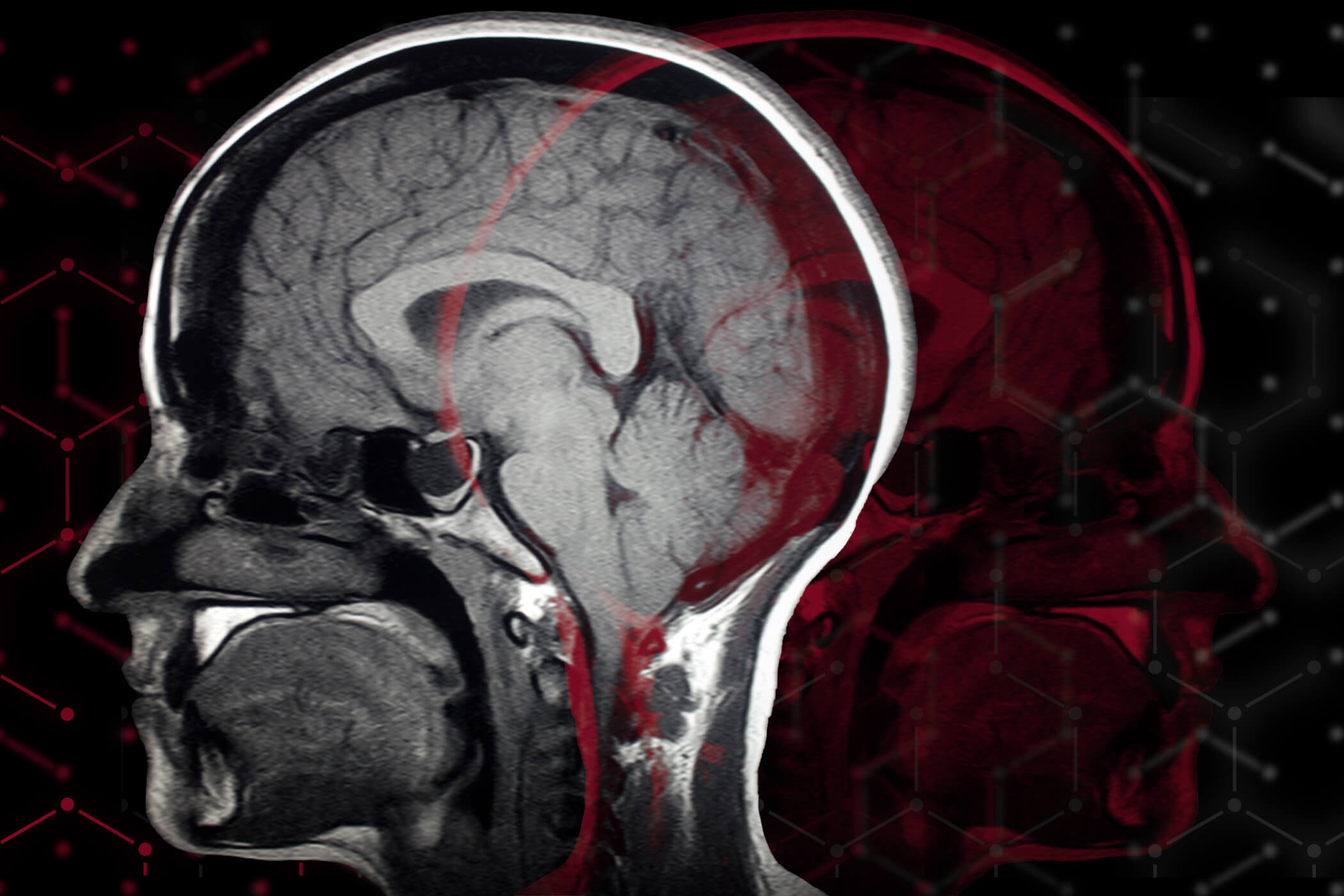

Researchers believe people's ability to detect one of the basic tastes, such as sweet, could be related to the density of taste buds on their tongue. Under this assumption, a person with a greater density of taste buds would find a cookie sweeter than someone with a lower density of taste buds.

"I think a better understanding of how taste papillae and taste buds are developed will help us to better understand how taste sensitivity is determined," said Liu, who conducted research on taste at the University of Michigan before coming to UGA in September.

Taste papillae are fingerlike projections visible on the tongue's surface. Each papilla holds taste buds, which contain chemoreceptor cells. These cells send information about taste to the brain.

Liu and her colleagues have identified several cell-signaling pathways, or sets of molecules involved in telling a cell what to do, that determine the pattern, density and size of taste papillae on the tongues of rats and mice. They also found the formation of the taste papillae can be altered by exposing the rodents' tongues to different chemicals that affect these pathways.

In a study published in Developmental Biology, Liu showed that one of the pathways involved in the development of taste papillae is the hedgehog-signaling pathway. The name refers to mutations in the pathway that cause taste buds of fruit flies — the organism in which it was originally discovered — to look spiky, resembling a hedgehog.

“If I use a certain molecule to interrupt the hedgehog-signaling pathway at specific stages of development, the taste papillae will be everywhere on the rodent's tongue," said Liu, who was awarded a $1.25 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to further investigate the development of taste buds and taste papillae.

She thinks the pathways involved in forming human papillae are similar to the ones she's identified in rats and mice. A better understanding of these pathways and organs may provide a way to fight obesity.

Cliff Baile, who directs UGA's Obesity Initiative, hopes Liu can bring a new perspective to UGA researchers already studying eating behavior and food addiction.

"As a taste developmental biologist, Liu brings a new area of research to the campus," Baile said.

Studying the way different foods or nutrients affect taste organ development could help researchers understand why the sense of taste differs among people. This knowledge also could help explain eating choices that lead to obesity. For example, people who are less able to detect the taste "sweet" might require more sugar to feel satisfied.