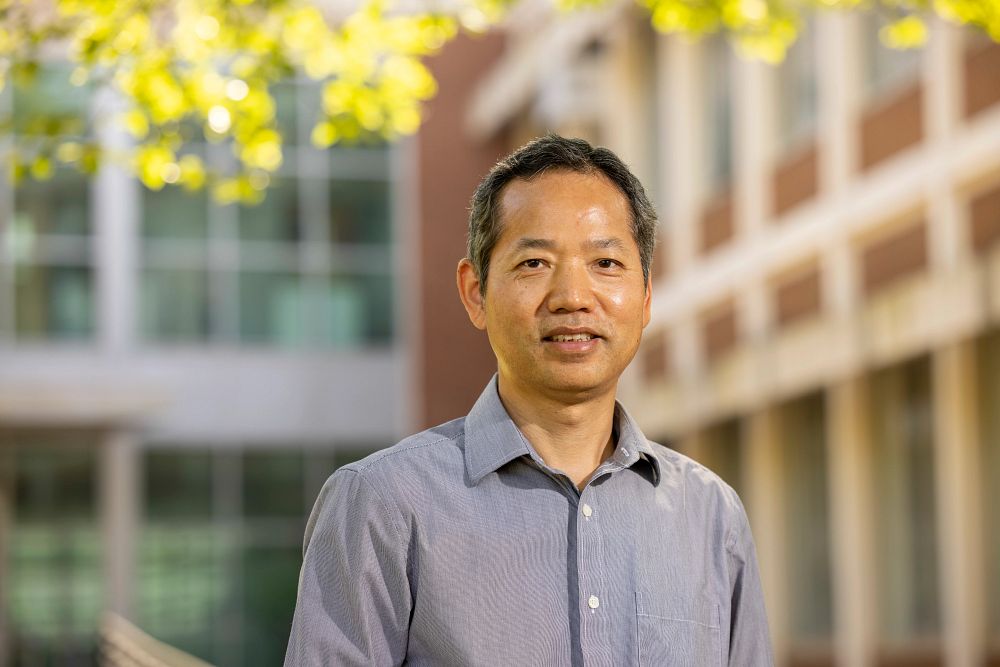

University of Georgia food scientist Joseph Frank has been awarded a $499,998 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to determine the risks associated with salmonella in dry and ready-to-eat foods.

Frank’s grant is one of 17 research projects funded by USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. Each project aims to improve food safety by helping control microbial and chemical contamination in various foods.

Salmonella cases high

Salmonella is a bacterium that causes an estimated 1 million cases of foodborne illness in the United States each year, said Frank, a researcher with the UGA College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. Close to 20,000 people are hospitalized and some 400 die due to salmonellosis each year, he said.

Usually, symptoms last four to seven days and most people get better without treatment. However, salmonella can cause more serious illness in older adults, infants and those with chronic diseases.

Poultry, eggs, raw sprouts and unpasteurized juices are common sources of salmonellosis. Cooking and pasteurization kill the bacterium in these foods, but not in dry and ready-to-eat foods.

Laying in wait

“When salmonella gets in these foods, it isn’t able to grow up but it doesn’t die every quickly. It tends to survive for very lengthy periods of time,” Frank said. “Salmonella can be in the marketing process and on the shelves for months before people consume it and get sick.”

Unfortunately for consumers, these foods don’t show signs of contamination like spoilage or off taste.

“These are ready-to-eat foods, and they are shelf stable foods,” Frank said. “ So they don’t spoil, but the salmonella can be in there and can survive for many months. Then whoever eats that food is at risk."

In 2009, almost 400 people in 42 states were sickened after eating contaminated peanut butter. Over the past 10 years, numerous salmonella cases have been associated with the consumption of foods like peanut butter, chocolate candies, dairy powders and nuts, Frank said.

“There have been a couple of peanut butter and peanut product cases and there have been outbreaks with chocolate and dairy powders, like whey protein and infant formula,” he said.

Uncovering the mystery

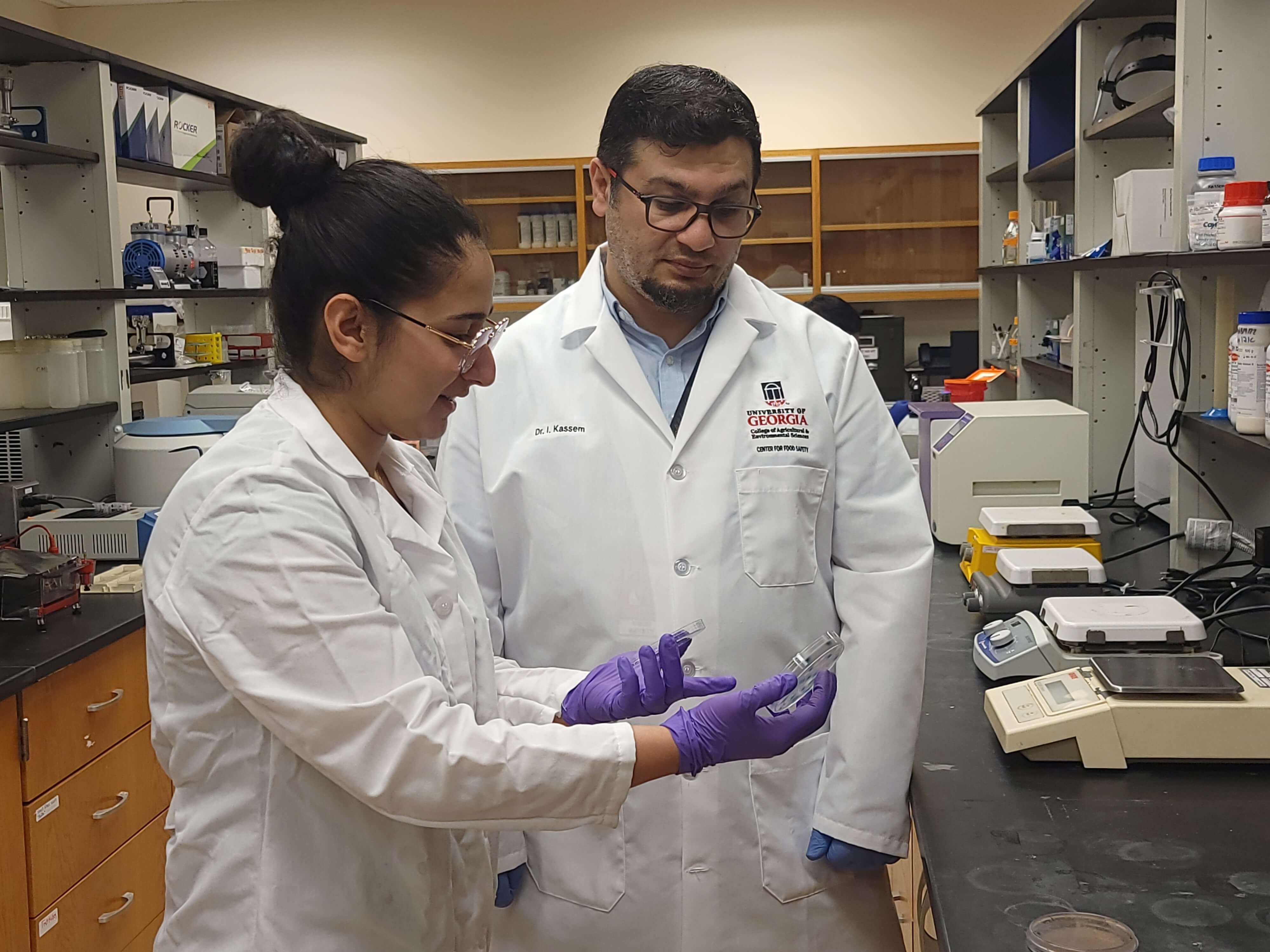

In his Athens, Ga., laboratory, Franks will use the grant funds to determine the chemistry makeup of these foods and how that affects the survival of salmonella.

“We don’t understand why it dies faster in some foods than others,” he said. “We plan to look at the characteristics of these dry foods and try to predict the survival of salmonella in these foods.”

Franks’ overall goal is to develop predictive models, or a risk assessment, for salmonella survival in dry and/or ready-to-eat foods.

“This is advanced research. We will come up with a means for regulatory agencies in the food industry to better access the risks of people getting ill from foods that might be contaminated,” he said. “In the end, we will have a tool that will allow the industry to assign a risk number on food products. Like, one person in every million will fall ill from eating the product.”

To protect themselves and their families from salmonellosis in dry and read-to-eat foods, Franks recommends consumers keep a close watch on recall notices and take action when necessary.