University of Georgia researchers have determined that toxic algae killed four cows on a cattle farm in Gwinnett County.

Georgia’s warm and dry spring created the perfect conditions for toxic algal blooms in ponds, they say, warning property owners to keep livestock and pets out of water that is discolored or opaque.

The toxic algae has been found in one other pond less than 10 miles from Atkinson Farms in Dacula, Ga., and researchers say it is very possible these are not isolated incidents.

“Pond owners should be mindful of the risks associated with toxic algae and take proper management steps to prevent or lessen the formation of an algae bloom,” said Rebecca Haynie, a toxicologist with the UGA Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources. “However, there are numerous species of common algae in the Southeast that are capable of producing toxin. So just because you have a bloom doesn’t mean you have something toxic in the water.”

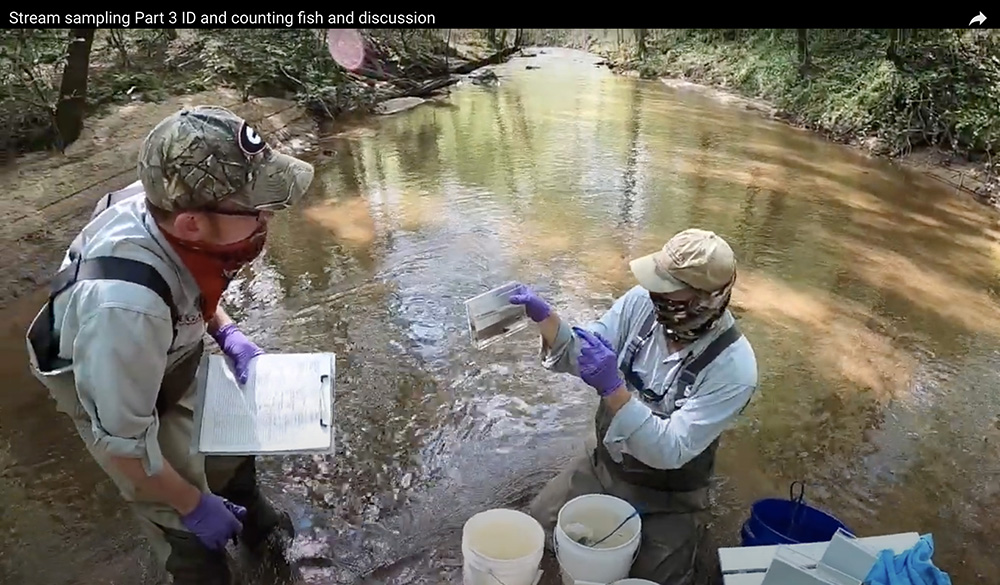

Haynie and other researchers have been working to clear up the algal bloom in cattle farmer Bill Atkinson’s pond, taking water and fish samples and treating the water with algaecide. Algae are a naturally occurring phenomenon, Haynie said, and typically flare up and then clear on their own.

Atkinson’s pond is the worst-case scenario, resulting from a perfect storm of conditions. Warmer than average temperatures and drought lead to increased water clarity and an influx of nutrients from the surrounding pasture, which created the ideal conditions for an algal bloom.

Unfortunately for Atkinson, the dominant species in the bloom was the toxin-producing species, microcystis. This blue-green alga, or cyanobacterium, is a potent liver toxin. Haynie said that when the Warnell team tested Atkinson’s water, the toxin level was so high they were out of test range. Her team treated the pond with algaecide twice to attempt to alleviate the bloom.

Color changes in a pond can be a clue that algae is blooming. Bright green water or water with a pea-soup-like surface scum should be avoided, and special care should be taken to keep pets and children away.

Pond owners who suspect their water is suffering from an algal bloom can purchase algaecide products from their local feed supply stores, Haynie said. She reminded pond owners to pay careful attention to the detailed labeling on these products, particularly because copper-based algaecides can be harmful to aquatic organisms, including fish. Using these products will only treat the symptoms so Haynie urges pond owners to address the causes of the bloom.

To help prevent blooms, leave vegetated buffers around ponds, limit livestock access and do not over-fertilize the surrounding area. Atkinson completely fenced his cattle off from the pond and is pumping water to a trough to hopefully begin remedying the situation. Pond owners also can contact their local UGA Cooperative Extension agent for more information.

Lawton Stewart, a UGA Extension animal scientist, said animals affected with the liver toxins often appear weak, exhibit muscle tremors, convulsions and have bloody diarrhea.

“These toxins can be fatal if ingested in high quantities,” he said. “Diagnosis may be difficult because the symptoms may easily be mistaken for other disorders more commonly observed in cattle, so a thorough evaluation of the farm is essential to rule out other causes.”

Dr. Lee Jones with the UGA College of Veterinary Medicine has received other recent reports of livestock found dead near a shallow pond. An algal bloom is the suspected cause. Toxin levels of blooms can vary, he said, and toxicity depends on the amount of water ingested. “There are three types of toxins: neural, liver (or hepatic) and a skin toxin that can cause a severe rash and itch.”

The liver toxins suspected of killing Atkinson’s cows, however “usually do not cause sudden death,” he said. “Sometimes the animal may have colic symptoms like abdominal cramps, excessive drooling, lose their appetite and be very lethargic.” Sometimes the effects are even delayed, Jones said, and animals won’t get sick for three to four weeks after drinking the contaminated water.

Jones recommends pond owners also contact their veterinarian if they suspect an algae bloom has occurred and their pets or livestock drank from the water. Veterinarians can conduct a blood test to confirm liver damage, he said.

Atkinson’s cattle grazed in a pasture near the pond and drank the water for more than 40 years without any problems until May 5. That’s when his first heifer died. Losing one head of cattle is not unusual, he said, so they didn’t suspect trouble until a second one died on May 12.

A third died on May 22 and the fourth died on June 5. By then, Atkinson and his veterinarian had developed a strong suspicion the pond water was the culprit. He moved the cattle away from the pasture and called Stewart at UGA.

Stewart referred Atkinson to Susan Wilde and Haynie at the Warnell School because of their work studying another deadly aquatic toxin that is likely killing American bald eagles who acquire avian vacuolar myelinopathy from the algae.

Atkinson said three other heifers have been exposed to the algae toxins; they have been sequestered and are being monitored. All of the cattle that have died or been exposed to the microcystin toxin are show cattle.

Pond owners can contact Wilde at swilde@uga.edu or Haynie at hayniers@uga.edu if they suspect a blue-green algal bloom.

The UGA Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources offers yearly classes on proper pond management. For scheduling information, see warnell.uga.edu.