Outrage from recent food safety incidents – which range from E. coli in spinach to salmonella in peanut paste and jalapeño and serrano peppers – has driven state and national leaders to take action, making the coming year one for some major food policy changes, said Mike Doyle, director of the University of Georgia Center for Food Safety in Griffin, Ga.

“The food safety laws we have today are archaic and out-of-date,” he said. “Most were designed 50 to 100 years ago when we had different food safety issues.”

One in four people get a food-borne illness every year, Doyle said. That amounts to about 76 million Americans annually. Most cases are mild and go away in a few days. The odds of becoming seriously ill from eating a serving of food in the U.S. are more than one in a million.

But food-borne illness isn’t the only issue. For every serious food-borne pathogen detected, there’s a cost. Just over a year ago, the now-defunct Peanut Corporation of America in Blakely, Ga., was linked to salmonella-tainted peanut paste that sickened 700 people and resulted in more than 3,600 products being recalled.

“It was reported [that] as a result of the PCA recall, Kellogg Company lost between $65 million and $70 million,” Doyle said.

During the tomato scare of 2008, the U.S. tomato industry lost an estimated $300 million in revenue. Florida growers bore the brunt of the recall, incurring up to $100 million in losses.

With these events still fresh in the public’s minds, both the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate are working to improve food safety regulations. On July 30, 2009, the House passed House Resolution 2749, known as the Food Safety Enhancement Act. The bill is now in the Senate. The Senate is debating its bill (SB 510), known as the Food Safety and Modernization Act.

“In general, the direction they’re going is a good one,” Doyle said of the bills. “We all have to be responsible for ensuring the safety of the food [supply]. It’s important that the government works with everyone in the food chain, [and] that the growing and the preparation are done right.”

HR 2749 would give the Food and Drug Administration greater regulatory powers. Specifically, they would be able to mandate a recall, instead of just suggesting one. It would require processors and producers have records available during routine inspections. It would also call for increased food traceability and record keeping, which would allow the FDA to track items implicated in outbreaks.

And it comes with a registration fee. Facilities holding, processing or manufacturing food would be required to pay $500 annually.

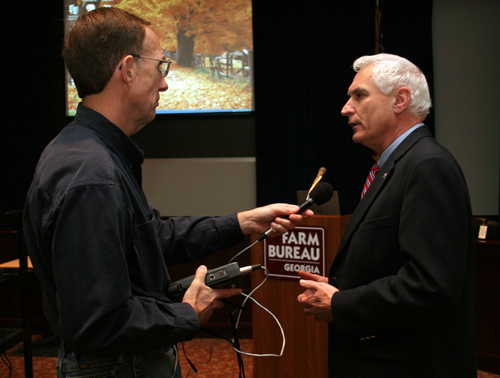

“Obviously, it’s going to add cost to your product,” Doyle told producers at a recent meeting in Macon. “I don’t think the costs are going to be astronomical, but if we want to raise the bar in consuming safe foods, there’s going to be a cost.”

The Senate bill would establish a food safety administration and administrator within the Department of Health and Human Services.

As the bill is currently written, the food safety administration would coordinate all food safety law and regulation enforcement, which includes food inspection, food-borne illness surveillance, food traceability and research. These functions are currently housed within the FDA, U.S. Department of Agriculture and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“This administration would be responsible for a national food safety program for all food consumed by Americans,” Doyle said. The bill would also require processors to maintain records for “one up and one back, or where the food they’re producing came from and where it will be going.”

Food-borne illness issues haven’t just brought about change on the national level. In Georgia, food safety regulations changed when Gov. Sonny Perdue signed Senate bill 80 into law in 2009.

The law now requires food manufacturers in Georgia to notify the state when they have a contaminated product.

“With the Peanut Corporation of America situation, the company was testing its products and found salmonella in many of its samples,” Doyle said.

Instead of reporting the problem or destroying the contaminated products, the company sent samples from lots contaminated with salmonella to a different lab for retesting.

The Georgia legislation will also increase the frequency of inspections and improve the state’s access to records. The act exempts foods regulated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, such as meat and poultry, Doyle said.

“The Georgia Department of Agriculture is currently in the rulemaking process to implement this legislation," he said.

They’re currently in the review process and are allowing comments on the proposed changes.