Unlike a roadmap, the molecular map identifies plant genes and where they're located.

"We have developed landmarks and determined how the landmarks are arranged with respect to one another (within the peanut plant)," said Andrew Paterson, a plant geneticist with the UGA College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences. "The landmarks enable us to determine what important genes, instead of cities, are nearby."

Mapping the genes of plants has revolutionized crop breeding over the past decade, Paterson said.

"Most major crops already have genetic maps, but the peanut was especially difficult," said Paterson, who began looking into the peanut genome five years ago.

The Peanut Highway

This map is the beginning of a framework for a physical map and

sequence for the peanut genome.

"The molecular map is like putting mileposts along the highways.

The physical map is like driving along the highways from milepost

to milepost," Paterson said. "The sequence is having total and

immediate recall of everything that lies along every

highway."

That kind of information can help plant breeders develop better

plants.

"One of the important uses of the map is to transfer desirable

genes from wild relatives and exclude undesirable genes. This is

badly needed in peanut," Paterson said.

John Beasley, a UGA Extension peanut agronomist, agrees. By

understanding genes, scientists can efficiently develop plants

with good traits, such as better quality and yields, he said.

Those Wild Relatives

Peanuts are native to South America. Many peanut species still

grow wild there.

"Some of the wild species have resistance or immunity to some of

our pest problems," Beasley said.

Technology could take those wild, useful traits and put them into

a peanut Georgia farmers can grow.

"Farmers would benefit because any improvement in yield and

quality will provide an economic benefit to the grower," Beasley

said. "And a more drought-tolerant cultivar would require less

water."

Consumers will benefit, too, from a higher quality product.

Better oil quality and chemistry will add to peanuts' reputation

as a healthy food, Beasley said.

Some Resistance

The peanut industry also needs a peanut that has resistance to

aflatoxin. Aflatoxin occurs when a certain mold attacks the

peanut plant. It can be dangerous if consumed.

"The entire industry, of which Georgia accounts for about 40

percent," Beasley said, "would reap benefits from knowing there

were cultivars with a much lower risk of aflatoxin

development."

Beasley sees only one negative: the public's perception that

genetic manipulation is wrong.

"What many do not understand is that with genome mapping and

identification, scientists can develop cultivars that would

require less pesticide. This would benefit the environment," he

said.

Genetic technology has become "central" in the development of

many crops, Paterson said. And it will continue to grow in

importance as the cost of the technology becomes cheaper.

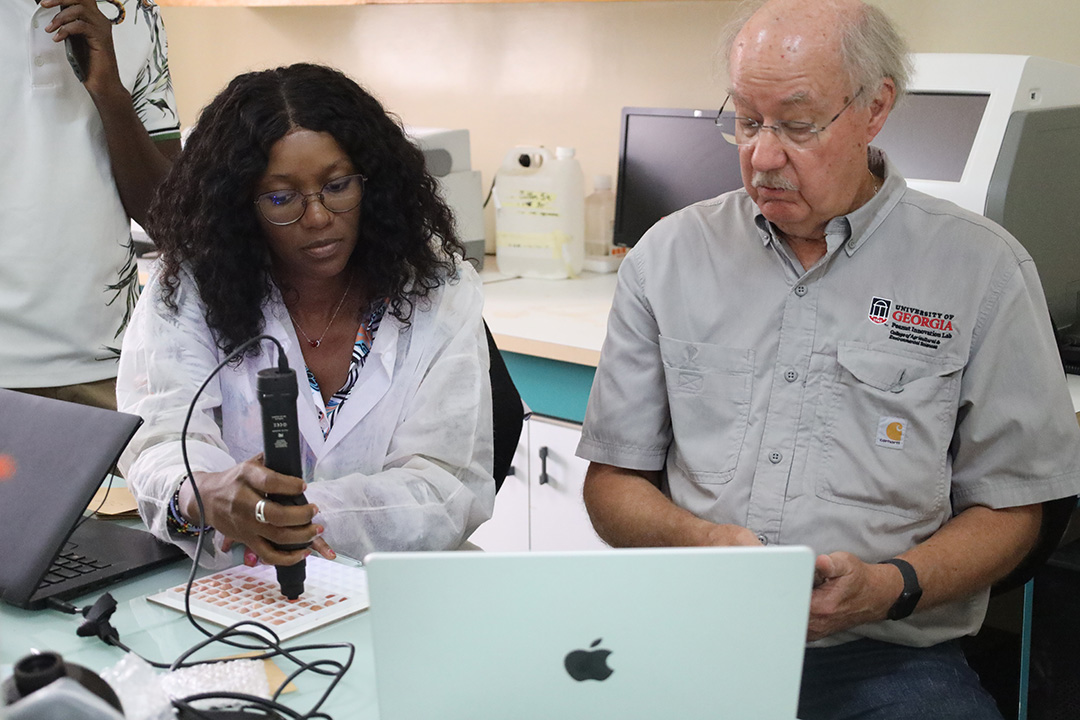

Paterson's lab in Athens, Ga., has also developed the world's

leading genetic maps for cotton, sorghum, sugarcane and buffel

grass. He plans to map Bermuda grass and cactus next.