They’re creepy, and they’re kooky. Mysterious and spooky. Some might even say they’re all together ooky.

But instead of being beloved and quirky like the Addams Family, bugs are decidedly less welcome in our homes.

While bees and butterflies often feel the public’s love, less conventionally attractive creepy-crawlies like cicadas and Joro spiders are left out in the cold—or, worse, squished.

“I think insect conservation is one of the most overlooked areas of conservation biology,” says William Snyder, a professor of entomology in UGA’s College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences (CAES). “They’re not huggable; not many species of insects are charismatic. But insects support so many ecosystems.”

Why should you care? Well, for starters, bugs are everywhere.

Insects alone make up more than half of all the animals on Earth. Add in the rest of the terrestrial arthropods, like arachnids, centipedes, and millipedes, and you’re looking at millions of species, many of which have yet to be identified, according to the U.S. National Park Service.

But don’t let their overwhelming numbers freak you out too much. Many of these bugs—like the ones you’ll meet in the coming pages—are harmless or even beneficial. And they need our help to keep doing what they do best.

They pollinate our fruits and veggies, help decompose organic waste that would otherwise pile up, serve as an integral food source for other creatures big and small, and so much more.

Insects, arachnids, and other critters. Oh my.

Ever wonder what makes an insect an insect and a bug a bug? Or are you more in the camp of “I don’t care what it’s called. Just keep it away from me”? Here are a couple of key tricks you can use to tell the difference.

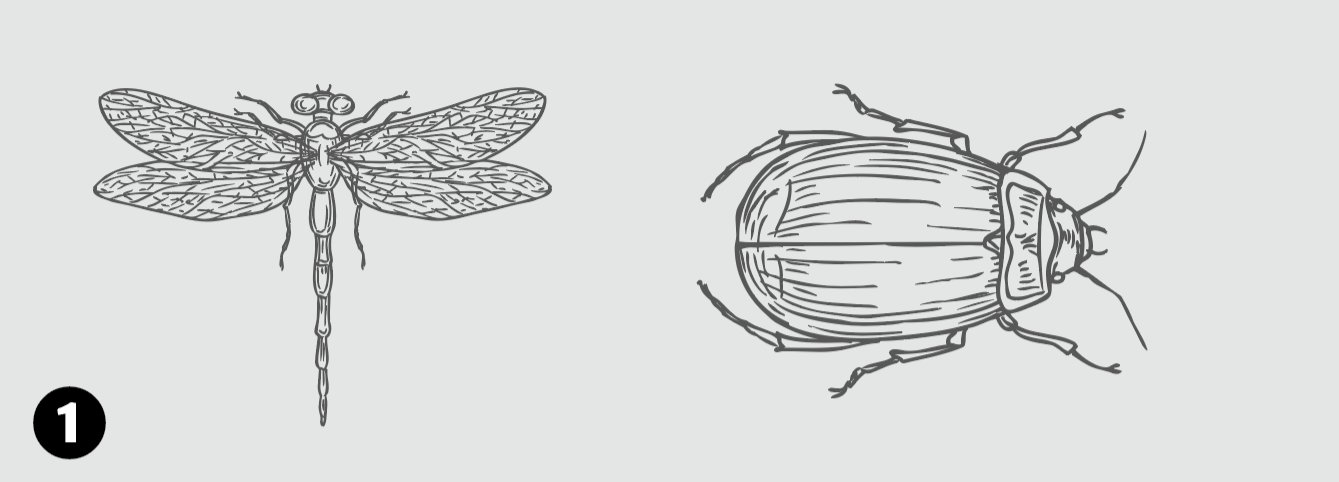

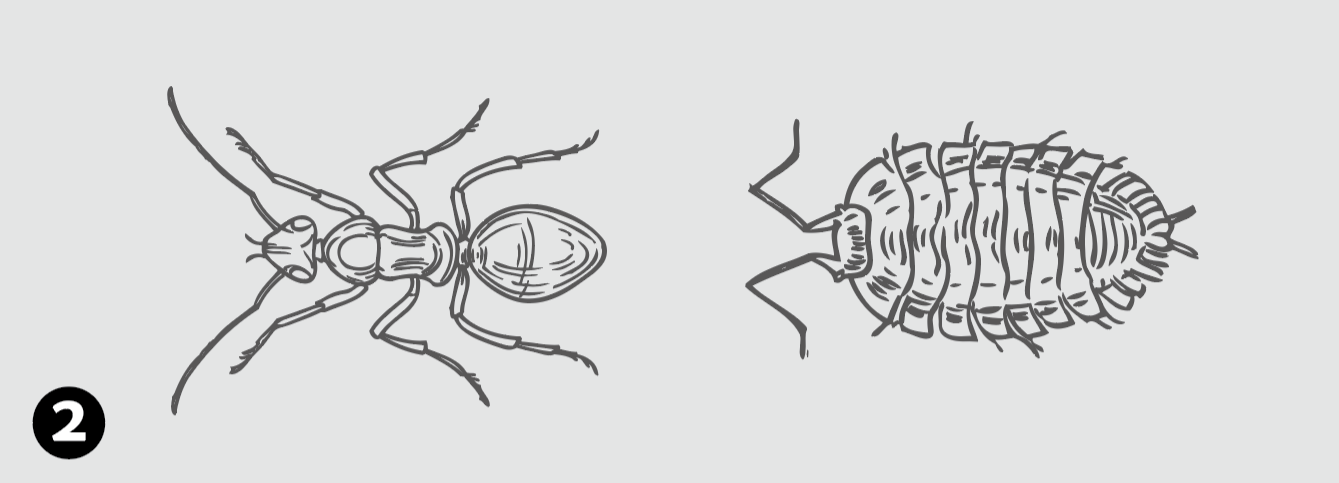

1. Number of body segments

Insects have three: a head, thorax, and abdomen. Sometimes it can be difficult to tell where one segment ends and another begins. The dragonfly, for example, has clearly defined segments. The segments on beetles, like ladybugs, are a little harder to spot since their wings fold over a chunk of their body. Meanwhile, an arachnid, like a spider or scorpion, has two body regions and lacks the antennae present on actual insects.

2. Number of legs

This is where it gets a bit creepier. Insects typically have three pairs of legs, so six in total. That means that critters like centipedes, spiders, and roly-polys (also known as pill bugs) actually aren’t insects. Instead, think ants, bees, and flies. You probably aren’t taking the time to count the legs on the mosquito that just landed on your arm before smacking it, but if you did, you’d find this blood-sucking bane of our existence also has six legs.

An Insect Apocalypse?

Insects are one of nature’s best adapters to change. Whether that change is in their environment or their climate, many species do a great job adjusting to new challenges.

Take the Joro spider.

After hitching a ride to the U.S. on shipping containers from Asia in the 2010s, the Joro spider found itself in new terrain on the East Coast. And the bright yellow-and-black arachnid is making the most of its migration, ballooning from a few spiders here and there to being spotted between powerlines, on top of stoplights, and even hanging above gas pumps.

Joros have an uncanny ability to adapt to urban landscapes and thrive where other spiders don’t. That adaptability leads researchers to believe these invasive creatures are here to stay. (Don’t worry, though. They’re pretty much harmless.)

There are legitimate concerns about the insect world’s well-being, but it’s more complicated than rumors of a mass bug die-off imply.

“On the one hand, you hear that all the insects are going to be lost,” Snyder says. “On the other, you hear that mosquitoes that carry malaria are becoming more widespread and that agricultural pests are increasing due to changing climates.”

“What we do know is that some insects are probably going to be harmed while some insects will benefit. You really have to take that big picture at a more continental scale over a relatively long time period to get the true picture of what’s happening.”

Royalty Among Butterflies

Insects are also incredibly resilient, regularly bouncing back from bad weather events or disease outbreaks.

Monarch butterflies are an ideal example of how an insect in trouble in one part of the world can thrive in others.

In recent decades, researchers have become increasingly concerned about the popular monarchs, watching closely as the number of migratory monarchs reaching their winter destinations continued to fall.

Studies from UGA scientists suggest that summer populations of monarchs in North America have remained relatively stable during the past 25 years. These breeding populations may help compensate for the species’ losses on its annual journey south.

Still, concerns about the insect’s migration persist, with recent work led by Andy Davis, an assistant research scientist in UGA’s Odum School of Ecology, and Snyder finding that monarchs are dying off at very high rates as they fly thousands of miles each winter to sites in Mexico.

Facing an increasingly common parasite called Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (or OE for short), decreasing habitat, increased insecticides, and changing weather patterns, monarchs appear to be facing an uphill battle. But it’s not a hopeless one.

“Monarch migration is in trouble,” says Sonia Altizer, the Martha Odum Distinguished Professor of Ecology. “But a single female monarch can lay 1,000 or more eggs, so they have the potential to recover. They’re pretty durable as far as insects go.”

Sonia Altizer didn’t set out to study monarch butterflies. But when she saw the species plagued by an understudied parasite, she knew she’d found her calling. (Photo by Andrew Davis Tucker/UGA)

People know monarchs are in a vulnerable position, and they want to help. Unfortunately, many of the efforts to “save the monarchs” may be harming them.

Home gardeners know that milkweed provides food for monarchs at their caterpillar stage and nectar for adults. But they may not realize there’s a huge difference in the growing season of our native milkweeds and that of non-native tropical milkweeds.

Native milkweed dies in the fall and winter, encouraging monarchs to begin their southward journey in a non-reproductive state, which is critical for them to survive their five-month stint in Mexico. Tropical milkweeds continue to flower until they’re hit by a hard frost, providing a resource for monarchs to keep eating and reproducing when they’re supposed to be migrating and overwintering.

“They see this milkweed, and it’s like candy to them,” Altizer says. “They can’t resist it. Some of those monarchs flying south will drop out of the migration and start breeding again. If they can, they’ll do that all winter long.”

That ramps up transmission of the OE parasite, which spreads from adults to eggs and caterpillars, and the burden of infection ratchets up with each generation. Rather than discouraging gardeners from helping the cause, scientists want them to grow plants that will help monarchs stay on their journeys.

“We want people to plant native milkweed, and we want them to plant nectar plants for butterflies,” Altizer says. “But we need to do it in a way that mimics natural habitats.

Joining the 10% Club

It’s not just butterflies that would benefit from this approach. Most, if not all, insects thrive in natural habitats, and it wouldn’t take much to make an impact.

Jennifer Berry was a comedian and actress. But when she decided to go back to school at UGA, all it took was a couple entomology courses with Professor Keith Delaplane for her to realize she wanted to center her life’s work on bees.

“I know the public loves their grass, but what if everyone could give up about 10% of their yard to help create wildlife corridors?” asks Jennifer Berry BSA ’98, MS ’00, PhD ’24, an entomologist and outreach specialist with CAES and UGA Cooperative Extension. The corridors don’t have to be complicated. In fact, making a difference might just mean planting a single tree.

“Trees are particularly great for honeybees,” says Lewis Bartlett, an assistant professor of entomology in both the Odum School and CAES at UGA. “A couple of mature tulip poplars are going to do a lot more than acres and acres of clover. These big old landscaping trees are absolutely critical to insect health.”

For some of our native bees that can only travel 100 feet or so, having these little pockets of habitat and food could mean the difference between a thriving colony of pollinators and death.

Lately, Berry’s been working with Scott Griffith, the assistant manager of UGA’s golf course and associate director of agronomy, to turn unused areas on the award-winning public course into pollinator habitats with trees, shrubs, and wildflowers.

“If we can do this at a golf course, we can definitely do it in someone’s back or front yard,” Berry says.

Lewis Bartlett always liked bugs, particularly bees. He describes bumblebees as the “Tauruses of the bee world, slow to anger but very slow to forgive” and says that while carpenter bees “look like they might kill you, they’re really just big cinnamon rolls.”

Bee Healthy

Bees aren’t the only insects being ravaged by parasites and disease outbreaks. But there are reasons to be hopeful.

Innovative discoveries include the world’s first bee vaccine from the UGA Innovation District’s Dalan Animal Health in partnership with CAES, the UGA Bee Lab, and the College of Veterinary Medicine.

In addition, UGA researcher-led efforts like Project Monarch Health, a citizen science project that harmlessly samples wild monarch butterflies to track the spread of parasites, and Joro Watch, which monitors the proliferation and expansion of the Joro spider, help protect our creepy crawly buddies and educate the public about the crucial roles insects and other bugs play in our ecosystem.

“Insects and spiders are so different from us,” Altizer says. “Their bodies are different. Their brains and sensory systems work differently. And I think maybe that’s one reason why a lot of people get put off by insects: because they’re so different and maybe seem strange. But for me, that fact makes them incredibly fascinating.

“I wish I could see what a butterfly sees and feel what a butterfly feels because I would be able to answer so many questions if I knew how they were experiencing their world. But the one thing I do know is it’s really different from how we see the world.”