Nestled among cappuccinos and traditional espresso lattes, a unique, golden-hued beverage has grown increasingly popular on cafe menus over the past several years. Recently advertised as a caffeine-free, healthy coffee alternative, “golden” turmeric milk is a fancified version of haldi doodh — a traditional Indian beverage often used as an at-home cold remedy.

Now researchers at the University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences (CAES) have developed an efficient method of making a plant-based, instant version of the beverage that maintains its beneficial properties while extending its shelf life.

Golden milk — also called golden or turmeric latte — consists of milk, turmeric and spices, and is a good option for people who want to avoid caffeine or coffee or enjoy a uniquely flavored beverage.

“It’s a very good beverage, especially if it’s cold outside, or if you’re sick,” said Anthony Suryamiharja, graduate research assistant in the CAES Department of Food Science and Technology.

Innovating for better shelf life

Turmeric includes curcumin — a naturally occurring compound called a polyphenol that has been studied for its potential anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, Suryamiharja added.

“If we can incorporate bioactive compounds like curcumin into plant-based milks to bring them up to the same nutritional level as cow’s milk, why not?” he said.

Curcumin is difficult and time-consuming to separate from turmeric. Existing methods typically require complicated extraction techniques that involve organic solvents and multiple days to process. In addition, the compound tends to break down over time, shortening its shelf life.

Inspired by golden milk, Suryamiharja, Hualu Zhou, food science and technology assistant professor, and colleagues wanted to investigate whether there is a way to extract and store curcumin within plant-based milk. Despite its many health benefits, the curcumin content in turmeric is very low — roughly 2% — but you can only obtain a significant amount from turmeric. Without extracting the curcumin for fortification purposes, consumers would have to ingest a significantly higher level of turmeric to see any potential health benefits from the compound.

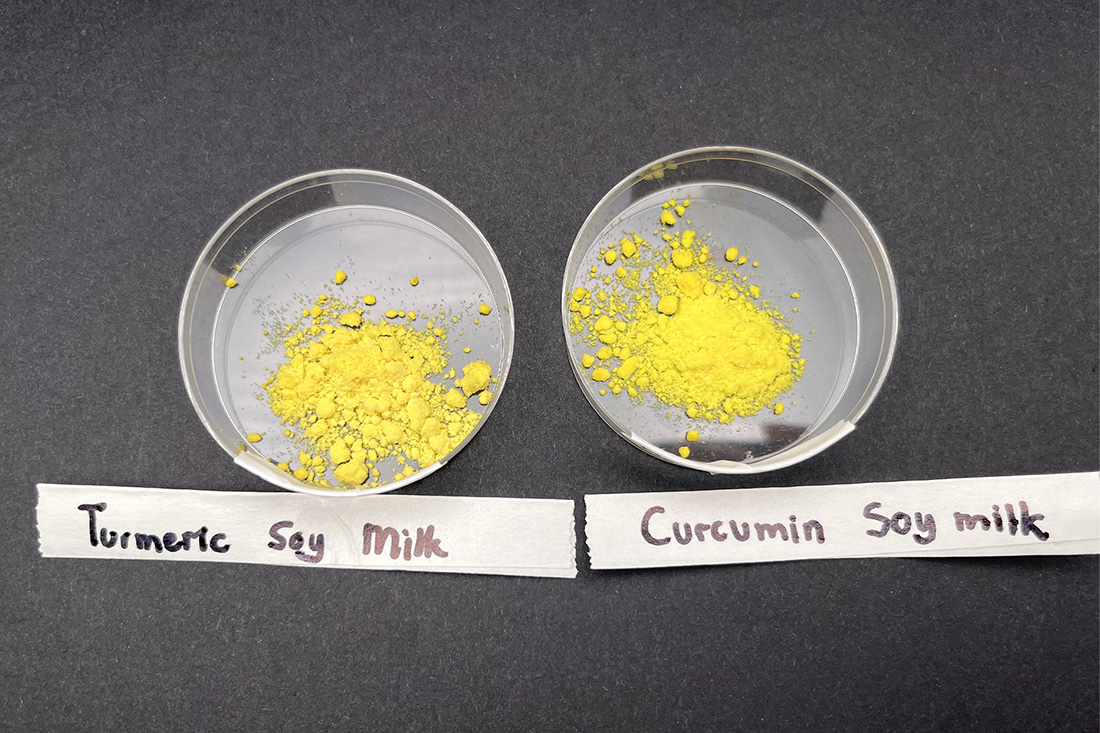

The team first added turmeric powder to an alkaline solution, where the high pH made the curcumin more soluble and easier to extract than in plain water. This deep red solution was then added to a sample of soy milk, turning it a dark yellow color. Because low-pH acids and high-pH bases are not the most pleasant foods and beverages, the researchers brought the beverage down to a neutral pH of around 7. The neutralized pseudo-golden milk could be enjoyed as-is, but to further preserve it, the team removed the water from the solution through freeze-drying, producing an instant golden milk powder.

Not only does the method extract curcumin from turmeric more efficiently than existing methods, but it also encapsulates the curcumin in oil droplets within the soy milk. This means that when consumed, our bodies recognize the curcumin as fat and digest it. The goal of this is to increase the absorption of curcumin so it is more likely to have an effect on the body. Encapsulating the curcumin also protects it from air and water, preserving it and keeping it shelf-stable for longer.

Upcycling fruit waste

While this work focused specifically on soy milk because of its high profile of indispensable amino acids — amino acids that cannot be synthesized in our bodies — Zhou and Suryamiharja say that it could be applied to other plant-based milks, providing options for those with allergies to soy.

In addition, their pH-driven extraction method could be used to upcycle valuable food ingredients and bioactives from fruit waste and loss. For example, this method can also efficiently extract water-loving micronutrients such as anthocyanins from blueberry pomace, the solid remains of blueberries after they have been juiced.

“When we use the same method, within around a minute we can extract the polyphenols,” said Zhou, who runs the Laboratory of Future Foods and Biomaterials and serves as Suryamiharja’s advisor. “We want to try and use it to upcycle by-products and reduce the food waste from fruit and vegetable farming here in Georgia.”

Though more research is needed before their instant golden milk appears on store shelves, the researchers’ initial result is promising — Suryamiharja reports that it tasted good, despite not being a frequent golden latte enjoyer himself

The researchers are presenting their results at the fall meeting of the American Chemical Society, a hybrid meeting held Aug. 18-22 featuring about 10,000 presentations on a range of science topics.

The team hopes that this work can help explain the chemistry behind what may seem like nothing more than a simple beverage, improving the drink’s nutritional value and convenience for those who enjoy it.

“Many people spend a lot of time in their kitchens, but they don’t realize that there is chemistry behind the tasks they are completing,” Suryamiharja said. “We are trying to explain these unspoken chemical moments in an easy-to-understand way.”

Learn more about the Laboratory of Future Foods and Biomaterials at zhouhualu.com. For information about research in the CAES Department of Food Science and Technology, visit foodscience.caes.uga.edu.