If you’ve ever wished that the orange juice you buy from the grocery store tasted like you squeezed it yourself — and stayed fresh at home — you may be interested in an electrifying project at the Food Product Innovation and Commercialization Center (FoodPIC) on the University of Georgia Griffin campus.

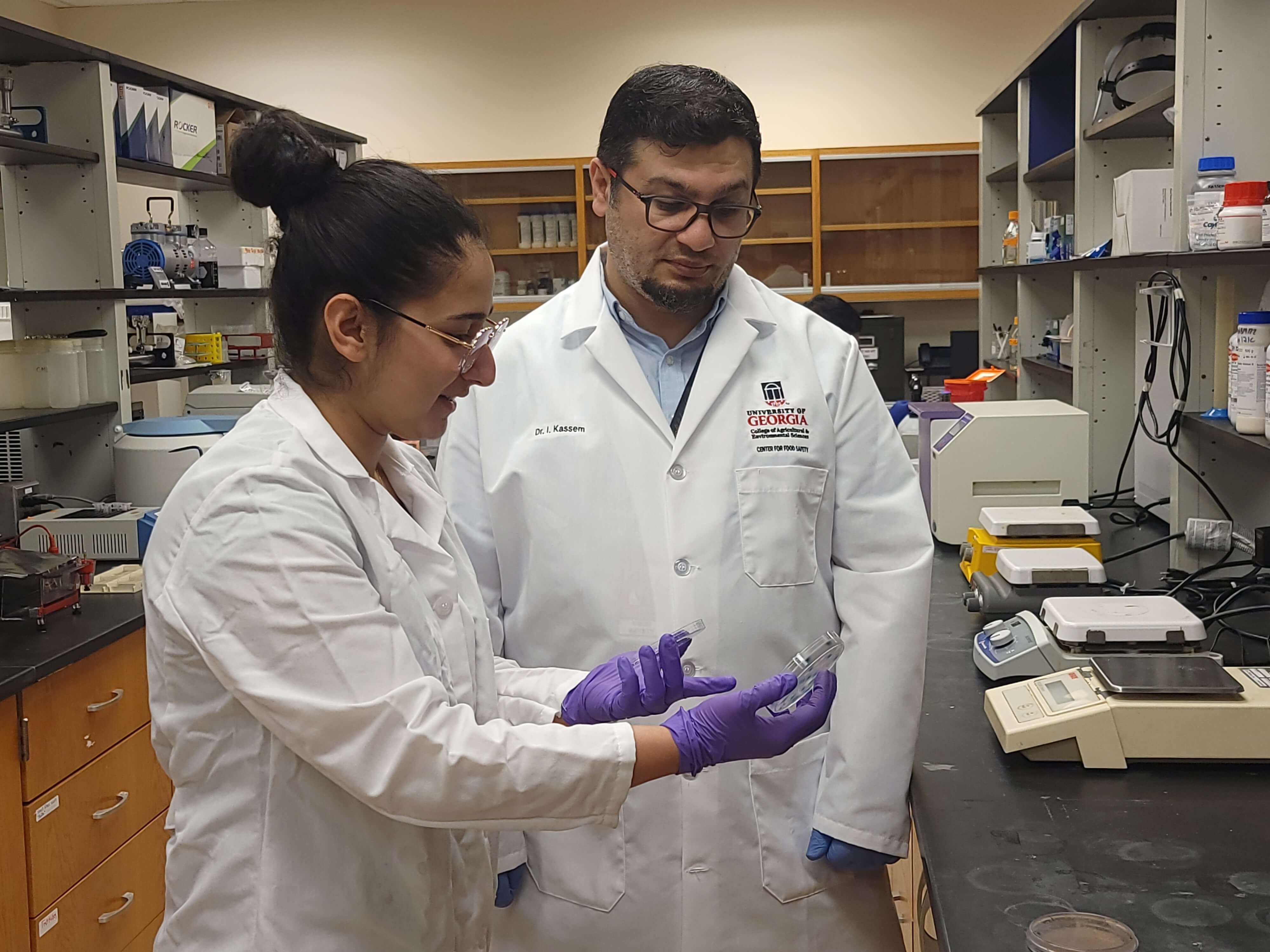

Food technology company Food Physics is working with FoodPIC scientists to perfect a technique known as pulsed electric field technology (PEF). An alternative to thermal pasteurization for processing food products, PEF uses short bursts of high voltage —15,000 volts per centimeter (V/cm) — to inactivate any harmful bacteria that may be found in the product.

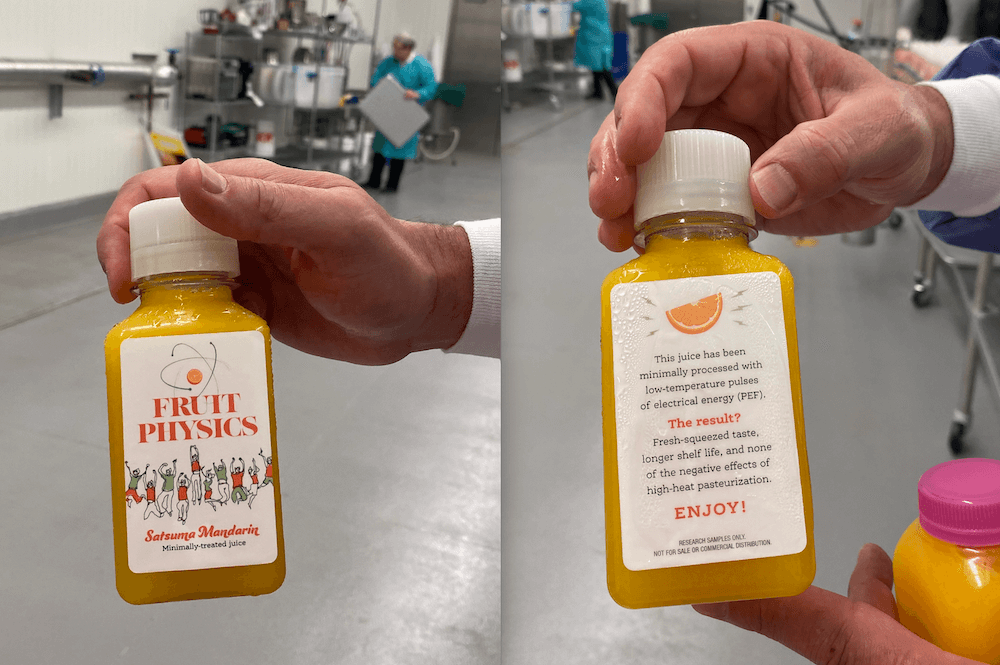

“The idea is to have a product taste as close as possible to fresh-squeezed, but be safe and have a commercially feasible shelf life,” said Jim Gratzek, director of FoodPIC.

When determining the shelf life of a product, scientists look at microbiological stability and product chemistry — both of which affect the shelf life of the product. Acidic juices which have been PEF treated to eliminate pathogens at a suitable level can be expected to have a shelf life of at least three months, Gratzek said. While some chilled-juice producers may code-date their products at less than three months based on taste and texture alone, the product can be consumed safely for much longer, he said.

Steve Hellenschmidt of Food Physics has been working with Gratzek and his team on processing a Georgia-made satsuma orange juice blend and a watermelon-lemon juice blend using the PEF process. The raw product for the juices was provided by Mark Paulk, operations manager of Borders Melon East in Adel, Georgia, and Kim Jones, owner of Florida Georgia Citrus in Monticello, Florida.

“The method we are using fundamentally changes the process for high-acid fruit juice production to create a higher-level product quality,” said Hellenschmidt. “Our aim is to be indistinguishable from fresh-squeezed juice.”

The company uses satsuma oranges because they want a high-end flavor that would be protected by their PEF process, Hellenschmidt noted, and the results from the test at FoodPIC were encouraging — the raw and PEF processed samples were indistinguishable in taste.

While working with FoodPIC scientists, Food Physics was able to produce test samples at a pilot factory scale, which helped confirm that taste performance was still outstanding at factory-comparable production rates.

“Our strategy is a pull strategy, to create a product to show how great it is, and then have the companies contact Food Physics,” said Hellenschmidt. “We think it is very effective if you have a good database.”

Food Physics markets PEF equipment produced by Elea, a food-processing systems company based in Germany. While there are other companies that use a similar approach, Elea is the world’s leading manufacturer of PEF technology, according to Gratzek. Elea, in partnership with Food Physics, has been working to build a market in the U.S. for three years.

Working with UGA on this project has been “a wonderful collaboration” from start to finish, noted Hellenschmidt, who looks forward to seeing the fruits of the company’s labors with FoodPIC.

“I have worked with Dr. Gratzek for nearly 30 years at various places,” said Hellenschmidt. “However, this is my first run at UGA. There are a lot of business opportunities to be had here. We appreciate all the work and all that has been done here. It has been a great experience.”

FoodPIC specializes in assisting food entrepreneurs and businesses develop and commercialize new food products. Those interested in forming a partnership with the center can reach out through the website at foodpic.uga.edu.

To read more about Georgia's burgeoning citrus industry, visit UGA Today.