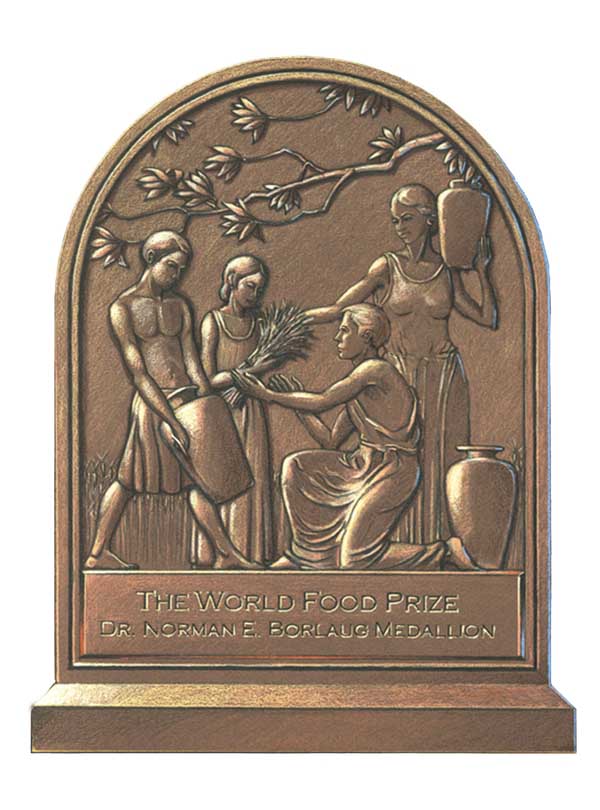

This week, the World Food Prize Foundation presented the Norman E. Borlaug Medallion to the U.S. Land-grant University System. Winning agriculture’s highest honor is welcomed validation for a century and a half of progress to educate working-class Americans and build the world’s most successful food production system.

The Borlaug Medallion honors world leaders and organizations that have made an especially noteworthy contribution to increasing food availability in the world and ensuring adequate nutrition, but aren’t eligible for the World Food Prize. This is only the fourth time the medallion has been presented.

Since President Lincoln signed the Morrill Act in 1862 creating public land-grant universities, the system has effectively changed the course of American society. The system’s scientists, scholars and public servants contributed to the growth of a dynamic, successful middle class that is the backbone of our workforce and future. The catalyst was equal access to higher education.

Public universities, public good

A luxury once afforded only to the elite, land-grant universities opened doors of higher education and rolled out the welcome mat of economic prosperity to average citizens.

Land-grant universities were established to direct federal and state funding to agriculture, engineering and mechanical arts education. We reap the benefits of that investment each time we put safe food on the dinner table, draw clean water from the tap and send our children to play in a healthy environment.

Land-grant universities are vibrant centers of innovation and discovery that deliver life-enriching education to our states’ citizens. Over the past 150 years, LGUs introduced countless scientific discoveries that formed a strong infrastructure and propelled U.S. agriculture to the forefront of world food production.

Because those discoveries came from government investment in public universities, they are a public good, equally accessible to all.

Agriculture’s success is paying big dividends for the U.S. economy. Now one of the nation’s largest employers, U.S. agriculture has more than 2 million farmers and about 19 million workers in allied industries, generating a $1.8 billion U.S. foreign trade surplus.

Laboratories and experiment stations at the state’s two land-grant universities – University of Georgia and Fort Valley State University – have produced vital advancements that help Georgia agriculture and our universities prosper. Among the innovations are new crop varieties, food safety technologies, irrigation techniques and environmentally sound pest control methods. Our scientists helped mechanize agricultural production, develop safer food preservation methods and define growing systems to protect and preserve resources.

For almost a century, Cooperative Extension agents have delivered those discoveries to farmers who use them to produce our food and grow our economy. They helped farm families and communities grow stronger and more resilient, too. Many of our students say contact with their county agent or participation in Extension’s 4-H programs planted the seed of aspiration to seek higher education that led them to our door.

Job growth outpaces student numbers

Inside our classrooms, students develop skills and gain knowledge that keep the agriculture industry moving. Each year, U.S. colleges of agriculture, life sciences, forestry and veterinary medicine graduate almost 30,000 students. Another 24,000 graduate in allied disciplines like biological sciences, engineering and health sciences.

But, we still don’t have enough graduates to meet industry demand. A recent study by Purdue University and USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture showed the U.S. economy could generate more than 54,000 job openings for college graduates in food, renewable energy and environmental specialties between 2010 and 2015 – 15 percent of them in agriculture and forestry production. That demands we increase the number of graduates in those areas by 5 percent.

Graduates entering the workforce face a complicated global market that requires greater understanding of the world around us. Our students can gain a global perspective through unique international study and research opportunities. Often those students see the impact of decades of land-grant university work firsthand. Our institutions have worked in Africa since the 1960s helping struggling nations develop a sustainable food system. In Asia we’ve helped countries clean toxins from soil and learn to protect water. Over the past 20 years, our institutions helped Eastern Europeans reconstruct their agriculture industry.

We extend our knowledge across the world because history proves there is no peace in a hungry world. Worldwide food security is a necessary building block to stability and prosperity for us all.

Funding the future

Our greatest struggle at home is dwindling funds for our institutions. An exploding federal deficit caused stringent cutbacks in federal funds, especially for research and extension. At the same time, state governments struggling to meet budget demands made even deeper cuts. For some land-grant universities cuts totaled more than 50 percent over the past three years.

These combined funding cuts left land-grant institutions with two options: raise tuition and look to industry for financial support. Neither is a popular choice.

Needed basic research produced from our labs wouldn’t garner industry funding since there is little chance for economic profit. Industry funds only those projects that can have a positive impact on their bottom line. Yet, this basic research is vital to continued success in agriculture.

Editorials maligning tuition hikes and burdensome student loans peppered newspapers nationwide this spring. According to the College Board, in the last academic year, the average in-state tuition at public schools was $8,244, compared to $28,500 at private schools.

Considering 97 percent of this year’s University of Georgia freshmen were awarded HOPE scholarships, they pay only a fraction of that cost. Even at full-price, tuition for a UGA 4-year degree is just $7,000 more than the average new car. A degree will last a lifetime. A new car rarely does.

Here’s the biggest question facing U.S. higher education: If governments can’t afford to fund public universities, students can’t afford tuition and corporations won’t fund unprofitable, but necessary basic research, then who will fund America’s public universities? Who will support critical research that keeps Americans fed?

If we allow higher education to revert to private institutions, a 4-year degree will be financially out of reach for those LGUs were created to educate. Critical research will belong to corporations with no motivation to share findings that strengthen our food production system. It flies in the face of everything the Morrill Act was signed to do – help America’s middle-class attain higher education and build a strong research and training system to support economic growth in agriculture.

When economic times are hard, tough budget decisions must be made at every level from the federal coffers to our own wallets. Where we choose to spend limited funds depends on what we value most. A safe, abundant food supply and a well-educated workforce should be high on America’s priority list.

Land-grant universities have 150 years of evidence they’re sound investments that produce high-quality results and pay sizeable returns to the nation. That return is not only economic, but also affords most Americans peace of mind that our grocery stores are filled with the safest, most affordable food in the world.

The 2012 Borlaug Medallion honors our success at building a reliable food supply at home and around the world. While debate about rising costs of public higher education swirls across the nation, the greater debate should be: Where would Americans be without it?

J. Scott Angle is dean and director of the University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences and chairman of the Board on Agriculture Assembly of the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities.