Latest

In the news

SPECIALTY CROP GROWER

THE NEW YORK TIMES

THE ATLANTA JOURNAL-CONSTITUTION

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC

-

Integrative Precision Agriculture

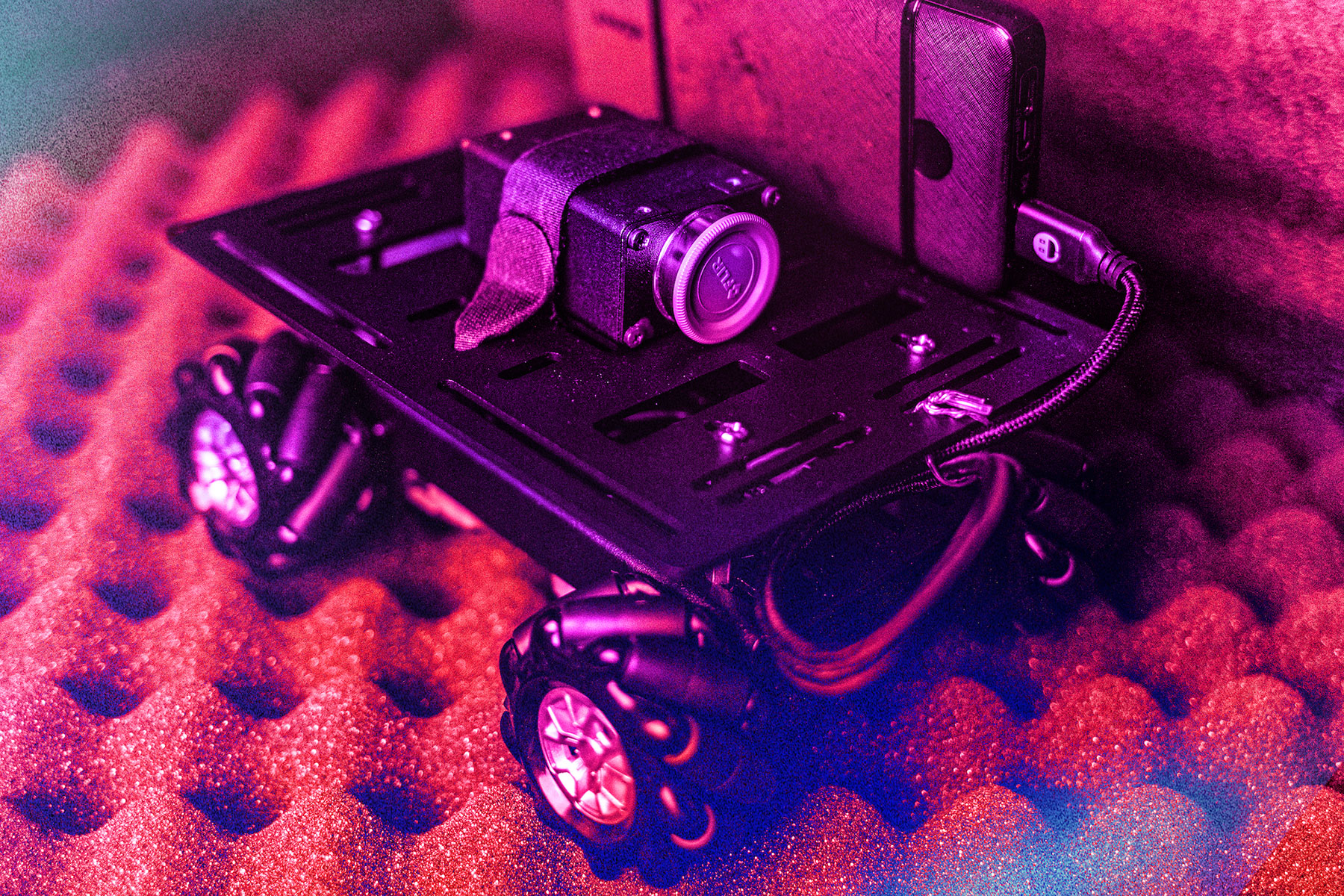

Integrative Precision AgricultureAt UGA, student researchers build the future of agriculture through robotics and solar innovation

Integrative Precision Agriculture

-

International Programs

International ProgramsCAES leads global project to boost local food systems in the United Arab Emirates

-

Integrative Precision Agriculture

Integrative Precision AgricultureCAES, partners demo future of agriculture at Grand Farm groundbreaking

GARDENING

Emergency Preparedness

-

Agricultural and Applied Economics

Agricultural and Applied EconomicsFighting fire with fire: How prescribed burns can help mitigate wildfire risks

-

Emergency Preparedness

Emergency PreparednessUGA Extension supports resilience in Georgia farm communities after Hurricane Helene

expert resources

Expert resources, also known as UGA Cooperative Extension publications, offer unbiased, research-backed advice to empower Georgians with practical, trustworthy information on agriculture, the environment, food, family and more.