When University of Georgia peanut pathologist Bob Kemerait does something, he does it wholeheartedly.

A passionate advocate for producers both near his academic home at the University of Georgia Tifton campus and around the world, Kemerait describes himself as “a field guy,” most comfortable among the rows detecting, diagnosing and addressing the myriad diseases and pests that threaten Georgia’s second-largest row crop.

Kemerait has been instrumental in the continuing development of the Peanut Rx tool that was created by peanut scientists at UGA and in neighboring states to help producers make critical crop decisions based on a number of risk factors including variety planted, inputs, row pattern, tillage, plant population, crop rotation, disease pressure, irrigation and planting date.

He's also been central to UGA's international extension efforts in Guyana, Haiti, the Philippines and, most recently, Gambia, traveling intercontinentally to help small-scale farmers improve peanut production as an important source of nutrition and income.

On Nov. 9, the Extension Committee on Organization and Policy of the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture honored Kemerait with the 2021 Southern Region Excellence in Extension Award.

“When we mention model Extension specialists, Bob’s name comes to mind instantly. His technical expertise, passion and people skills are the foundation for the impact he has on both our agent workforce and the commodities he supports,” said Laura Perry Johnson, head of UGA Cooperative Extension. “Dr. Kemerait is a true public servant in all aspects of his life.”

In July, Kemerait was chosen as the recipient of The American Phytopathological Society (APS) 2021 Excellence in International Service Award for “outstanding contributions to plant pathology by APS members for countries other than their own.”

Peanut Rx

True to his seemingly perpetual energy, Kemerait joined UGA on March 1, 2000, exactly two days after completing requirements for his doctoral program at the University of Florida.

“I finished everything and turned it in on Feb. 28, 2000. That was a leap year, so I moved to Tifton on Feb. 29 and started my job on March 1,” he said, a broad smile on his face. “I was fortunate that what I did for my Ph.D. project — working with peanuts, working with farmers, working with county agents — allowed me to step right into this role. There was a learning curve, but what I had been doing was directly applicable to what I am doing now.”

When Kemerait began studying plant pathology, researchers were using a tool called the Tomato Spotted Wilt Risk Index to determine producer risk for tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV), a virus that can infect more than 1,000 species and can be devastating to peanuts. Transmitted by tiny sucking insects called thrips, TSWV has spread throughout the Southeast since it was detected in peanuts in Texas in 1971, causing billions of dollars in crop losses.

Building on the model of the TSWV risk index, Kemerait worked with UGA plant pathologists Albert Culbreath and Tim Brenneman to develop a separate fungal disease risk index. Eventually Kemerait suggested that they merge the indices into a one-stop shop that both determines the risk for a number of diseases and provides management recommendations for producers based on their results.

“What we were designing would not only be a risk index that would tell you if your risk was higher or lower for certain problems based on the information you put in, but how you could manage diseases both before planting and during the growing season,” Kemerait said. “We developed programs where we could recommend how often to spray based on risk. It was all research-based and we documented all of the results.”

The team’s efforts and the results of the tool captured the attention of international agricultural company Syngenta, which became a corporate partner to support the new tool.

“Syngenta was willing to partner with us because they were of the opinion that whatever was good for the growers was good for them — because whatever keeps the growers profitable is what is going to keep their company strong,” Kemerait said. “Today a number of companies support Peanut Rx and I think this truly shows the trust and partnership between UGA Extension and the agricultural industry.”

At Syngenta’s suggestion, the team developed a “brand” for the expanded diagnostic tool, and the name “Peanut Rx” was contributed by now-retired UGA peanut entomologist Steve Brown, Kemerait said.

“The Peanut Rx tool, at its core, is using everything we know from our research. It involves everything we have done and everything we are doing at the University of Georgia across disciplines — from agronomy to entomology, even to weed science — captured in a relatively simple document the growers can use. The whole package is now available in an online form that encompasses everything we know about the biology of these pathogens, the development of these diseases, and how growers can affect risk. All of the research, not only from Georgia, but from other institutions, is right there,” he said

Getting to growers

Growers have embraced the system, in large part due to the effort of UGA Extension agents who have brought the tool into the field.

“Our Extension agents are the tip of the spear out there. They are the educators, and they recognize that these factors — variety, planting date, row spacing, seed spacing — all have an impact on disease. The agents are the ones who are really driving the implementation at the farm level,” Kemerait said.

As research progresses on important and emerging diseases and pests, that information is added to the system.

“We are constantly making annotations — it's a living document,” he added.

Kemerait currently heads a committee of researchers from UGA, University of Florida, Auburn University, Clemson University and Mississippi State University that convenes every year to assess Peanut Rx and add the latest available research-based information to the tool.

“All of the research, all of the variety testing, the surveys, will go in and we will adjust it to whatever is new or changing,” he said. “It is still being developed and implemented. We’ve got the basic Peanut Rx, but efforts are now underway to incorporate climate predictions. We are looking to use real-time modeling information on the impact of climate — whether it's saying that it is an El Niño or La Niña year or a neutral-type year — and the impacts of the kind of weather you can expect during the winter, which is certainly going to have an effect on your disease and insect risk.”

The success of the Peanut Rx risk index has inspired other risk index tools in agriculture.

“That, to me, is the true measure of the impact of Peanut Rx: You can look around the country and around the world at others who have used Peanut Rx as a building point,” Kemerait said.

Peanut ambassador

Beyond the impact his involvement with Peanut Rx has made, Kemerait has pursued his enthusiasm for international research and Extension work in peanut production. When he first came to UGA, he asked his supervisors about the possibility of working abroad, which led to peanut-related projects in Guyana, Haiti and the Philippines.

“The wonderful thing about peanuts is that, if you go into developing countries around the world, peanuts have several things that are critically important as a crop. First is the nutritional value of peanuts, and second, peanuts are a favorite crop that can be grown in addition to whatever a farmer is already growing,” he said. “In Guyana peanuts are grown to buy school uniforms or to put a roof on the house, because you can turn peanuts into cash. The whole objective was to develop the industry and to improve their production and to create a market for what they are growing.”

While he has had to counter arguments from some back home that improving peanut production in other countries increases competition for American producers, he said the Extension-type support the programs provide not only benefit the countries where they are established, but what is learned abroad can help domestic growers as well.

“When you go to these countries, many times farmers are growing peanuts as they might have a hundred or more years ago. Often they have little or no training as far as how to improve their production or address diseases. It's not in any way about competing with farmers here in the U.S., it is doing what you can to help people you would want to help in a small way because it is improving the economics of the region and the lives of people,” Kemerait said, mentioning a successful program that incorporated locally grown peanuts into a government-funded school feeding program in Guyana.

Kemerait's international work has laid the groundwork for even broader impact.

“Internationally, once people start to know your name, once you have some credentials to show that you have done this before and made a difference, doors that were locked shut before are now opened to continue the momentum,” he said.

Patricia Wolff, founder and CEO of Haiti's Meds and Foods for Kids, spoke to this directly, saying, “Dr. Kemerait has improved the lives and livelihoods of smallholder peanut farmers in Haiti. ... Our list of skills needed was long and our list of skills available was short. Dr. Bob rolled up his sleeves and dug into our situation with excellent, pragmatic and culturally appropriate problem-solving.”

Kemerait credits the faith put in him by John Sherwood, former head of the Department of Plant Pathology at CAES.

“He told me I had an unusual program that wasn’t the standard for an Extension specialist, but he saw what I was doing in Georgia and he gave me all the rope I needed to expand that throughout the Southeast and across the country. He said, ‘I think it is good for the University of Georgia, but you bring that rope back and show me what you’ve done with it,’ and I did,” Kemerait said.

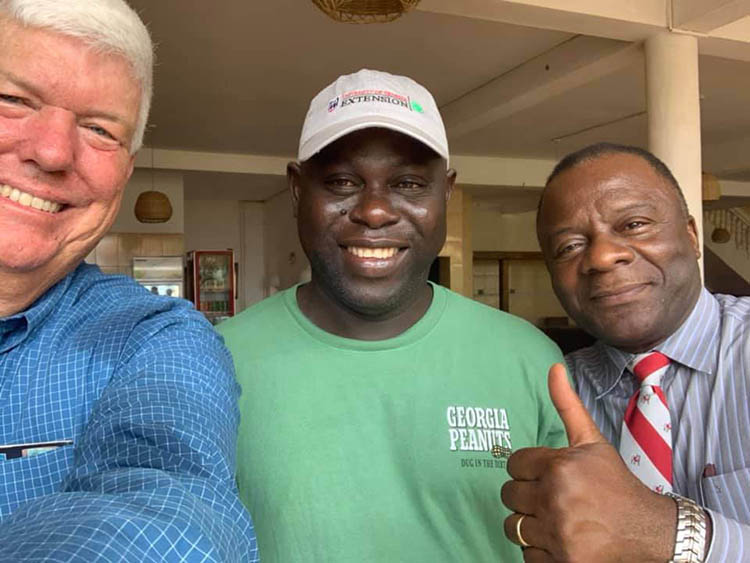

During his time at UGA, Kemerait has taken dozens of students and colleagues on international trips to Guyana, Haiti and the Philippines, where he has also recruited students to study at UGA. He recently returned from a trip with agricultural and applied economics Professor Greg Fonsah to the African nation of Gambia. While there, they met with government officials including President Adama Barrow. Kemerait was invited by the Ministry of Agriculture on behalf of Gambian farmers to identify ways UGA faculty could help improve peanut production in the small nation.

“That is what I love most about the University of Georgia and my job. I have been given the opportunity to integrate every aspect of my career into things that make a difference both statewide and locally. Through the course of professional activities, joint projects and training graduate students, the University of Georgia has impact on an international scale,” said Kemerait.

Pursuing purpose

Kemerait says that his international work has influenced him as a person and as a researcher.

“It is a two-way street. We’re not going anywhere to give secrets away, but we do provide education. We are not selling the secret recipe to growing peanuts, we're going over to help them to improve, but we also bring things back,” said Kemerait, relating the story of a colleague who was working with peanut producers in Nicaragua. “One of the hardest parts about controlling disease in peanuts is getting the fungicides you spray on the plants where it needs to be, which is the stem. Tim Brenneman was working in Nicaragua and he watched them spray at night when the leaves of the plants fold up so you have a clear path to spray. It’s a simple idea, but before he went over there and saw that, it wasn’t something that we did here. Now we recommend spraying peanuts at night as a way of improving management of soilborne diseases affecting peanut.”

That is just one an example of the kinds of traditional practices and professional insights that provide a different perspective when Kemerait is at work in south Georgia.

“It gives a different way of looking at things. We are also finding that, by working with professional peanut breeders in other countries, we get an idea of other diseases or pests that we are not aware of that may come back to us and be of importance,” he said. “If you’ve never been abroad, you can become myopic thinking the American way is the only way, is the best way.

Exchanging methods and viewpoints for growing peanuts gives Kemerait a more holistic view of production problems shared across the globe.

“Once you travel outside the United States, you see that there are a lot of other hard-working people in the world and there are a lot of other ideas that make me a better researcher at the University of Georgia. Because of work in places like the Philippines, Guyana and Haiti, I've been able to see peanut production and problems with peanut production from a different perspective,” he continued. “Peanut farmers everywhere are struggling with the same problems our famers have here in Georgia. They may not have the same technology or tools we have, but when you get a chance to look at problems the way somebody else does, that is eye-opening. And it makes you appreciate what we have in Georgia, and in the United States, that much more.”

Summing up, Kemerait adds, “I am blessed to be a part of UGA Extension. It's the very best job in the world. We are family.”